For this Russian journalist, the family trade is dissidence

Zoya Svetova, 62, is part of a Moscow family with a history of almost a century of activism, and government-imposed punishment, in Russia. She was interviewed before the Russian invasion of Ukraine and again on March 2

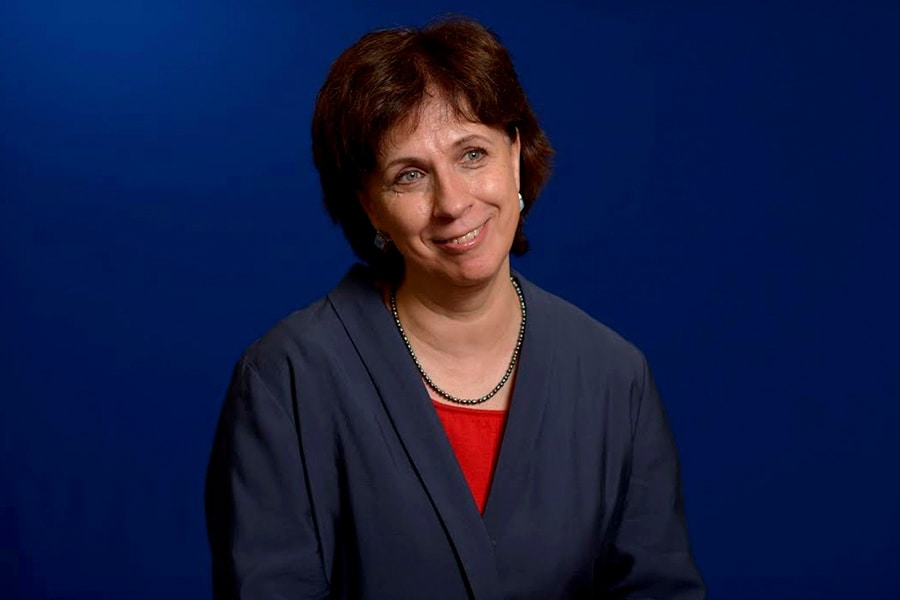

In a handout image, Zoya Svetova, 62, a Russian journalist and the 2018 recipient Magnitsky Human Rights Award. Four generations of Zoya Svetova’s family have stood up to repression. The invasion of Ukraine has shaken them but also given them reasons for hope. (Via the New York Times)

In a handout image, Zoya Svetova, 62, a Russian journalist and the 2018 recipient Magnitsky Human Rights Award. Four generations of Zoya Svetova’s family have stood up to repression. The invasion of Ukraine has shaken them but also given them reasons for hope. (Via the New York Times)

Zoya Svetova, 62, a journalist, is part of a Moscow family with a history of almost a century of activism, and government-imposed punishment, in Russia. She was honored in 2018 with the Magnitsky Human Rights Award, named after a nonpolitical Russian lawyer and tax adviser who died after being beaten in prison, and more recently received a Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest merit. She was interviewed before the Russian invasion of Ukraine and again on March 2.

Q: Your parents and grandparents were called “enemies of the people.” Your son, Tikhon Dzyadko, editor-in-chief of TV Rain (Kanal Dozhd), the only independent TV station in Russia, just left the country with his family, fearing imminent arrest. That was on the same day that Rain was ordered off the air — and on the five-year anniversary of a 10-hour search of your apartment by the Russian authorities. Is being “enemies of the people” somewhat in your family’s tradition?

A: I recently wrote to the FSB (Russia’s Federal Security Service, the successor to the Soviet KGB) seeking the records of my grandmother who served five years in a labor camp in Arkhangelsk in Russia’s far north because she was married to an “enemy of the people,” my grandfather Grigory Friedland, historian of the French Revolution at Moscow State University. He was arrested during Stalinist purges and executed in 1937. She spent five years there and I want to read her file.

My mother, Zoya Krakhmalnikova, a dissident of the Soviet 1980s, also spent one year in jail and five in exile in Siberia, where my father, Feliks Svetov, joined her after he served one year in jail.

There is a continuum here. I am not yet worthy of such a title. (Laughs.) But we’ll see.

©2019 New York Times News Service