Internet Saathi: Improving digital literacy among women

Google India and Tata Trusts' initiative has benefited 17 million women in rural India, bringing with it economic freedom. The workforce of the future will be more gender-balanced

Vandana Potdar (extreme left), familiarises rural women with the internet at Karandi village in Maharashtra; Image: Mexy Xavier

Vandana Potdar (extreme left), familiarises rural women with the internet at Karandi village in Maharashtra; Image: Mexy Xavier

It’s not without reason that the phrase ‘papad belna’ denotes hard work. Or as Manisha Abhang of Karandi village, about 35 km from Pune, calls it, ‘traas’. Faced with the problem of how she and other women from her village could make this task easier, they turned to the internet to look for an automatic papad-making machine. They haven’t bought it yet, but are piqued about its prospects already. “We can make about 100 papads a day while two women using the machine can make about 1,000 papads a day,” says Abhang, 40, part of a collective of eight women in her village who started a business making potato chips last October and are now looking to diversify into papads.

It’s a story that goes back to last June when Vandana Potdar, trained and tasked with the job of familiarising rural women with the internet as part of Google India and Tata Trusts’ Internet Saathi programme, arrived in the village. The programme was launched in 2015 with the objective of improving digital literacy among women in rural India and Potdar, 29, a resident of nearby Shikrapur village, was assigned a cluster of villages in the area.

When she started visiting houses in villages to teach women, some households told her the women didn’t have time for all this, while others kept her waiting outside for an hour or two until they cross-checked her credentials. But she persisted. If someone had to go work in the fields, she would teach them while they worked, showing them videos of sowing crops and soil testing. If someone was pregnant, she would show her maternal health care videos. With housewives, new recipes worked. She helped others look up new designs for clothes, how to shop online and use mobile wallets, and also encouraged them to make and sell things to earn an additional income.

Forty-year-old Rani Bhagwat—an entrepreneurial spirit who has done stitching and beauty parlour courses and runs a business from her shop in the village—is another woman whom Potdar introduced to the internet. Today, she looks up new designs for blouses, for which she charges as much as ₹500, as against the ₹100 for the simpler ones she made earlier. Other women make striking silk thread bangles that they sell from Bhagwat’s ‘Saundarya Beauty Parlour’ situated in front of her house.

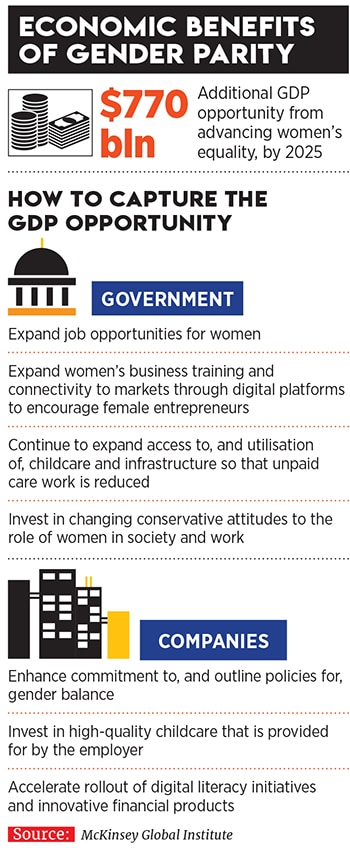

According to a May 2017 McKinsey report, more than four billion people, or over half of the world’s population, are still offline. About 75 per cent of this population is concentrated in 20 countries, including Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Pakistan and Tanzania, and is disproportionately rural, low-income, elderly, illiterate and female. The value of connecting these people is significant to help them enter the global digital economy. Besides, an online business requires less capital and enables women to work in the gig economy, while digital banking levels the playing field in terms of access to financial services.

In India, data from the Internet and Mobile Association of India showed that only 18 percent of internet users were from rural areas in 2015. “And among that, only one in 10 were women, which means there is a huge skew towards women not being able to access the internet,” says Raman Kalyanakrishnan, head-strategy, Tata Trusts. Familiarity with the internet and smart devices, he adds, had been identified as one of the key skills required for the future because it played a great role in terms of improved incomes, knowledge, access to opportunities and access to government schemes.

The Internet Saathi programme, launched on a pilot basis in 5,000 villages in rural Rajasthan to address this digital divide, has been through various adaptations. “The first pilot was like a four-hour training session where we would invite women from the community and tell them about the medium,” says Neha Barjatya, chief internet saathi, Google India. However, they realised that though women wanted to learn, they don’t travel far or don’t have the time, so they rethought the model and started taking a training cart to the villages. Finally, they decided to have someone from the community to teach them, the model they launched with in July 2015.

While Google takes care of the technology aspects, Tata Trusts has the expertise and knowledge in implementing the initiative at scale. The objective is to cover 3,00,000 villages by end of 2019 and today, according to data from Google, they have covered over 1,70,000 villages in 17 states, benefiting 17 million women. In 2017, the ratio of women who accessed the internet also went up to three in 10.

An impact study last year among the women who were being trained as well as the internet saathis showed that the social standing of women has significantly improved. “Three to four days ago, I met this saathi from Bihar, and she said, ‘I don’t have to depend on my husband for everything. I don’t have to wait for him to go and buy things.’ She started netbanking herself and the second thing she said was that today her son comes to her and asks her for money. Earlier, he used to always ask his father,” says Barjatya. Women who had been trained by saathis were also three times as likely to participate in village-level meetings and social causes.

From an economic perspective, “nearly 43 percent of the women responded saying they have learnt a new skill after having been exposed to the internet and about 45 per cent of the women reported that they have managed to identify newer ways to save their income,” says Raman K. Upskilling has also resulted in micro enterprises. “For instance, there is a saathi down south who started a lemongrass oil enterprise and another who started a weaving organisation in the Northeast,” says Barjatya.

Not stopping at digital literacy, the programme is being extended with the Foundation For Rural Entrepreneurship Development (FREND), a digital-based livelihoods programme for the internet saathis set up by Tata Trusts and supported by Google that was launched last December. “With the programme, we are saying that if the saathi needs to be active in her community we need to generate income streams for her,” says Raman K.

Opportunities include those where the saathis could be a behaviour change communications agent for her village; collect information and create insights that could then be used so that programmes are implemented better; be a monitoring agent for other programmes; and encourage them to be digital-based entrepreneurs, for instance, by providing subsidised printers that they can use to generate income. “The vision for FREND is to be able to generate digital-based income for about 1,00,000 saathis by 2022,” says Raman K.

Meanwhile, in Karandi, Potdar, who was also part of the Sakal Group’s Taniskha Foundation and taught women cooking, stitching etc, seems to have social work running through her veins—she has signed up for a BSW course and plans to do an MSW. In a country where women have reservations in local self-governance bodies but often end up being figureheads who do what their husbands tell them to, she recollects how she showed the sarpanch of a village what her rights and duties were as well as videos of how roads are made. “The sarpanch now takes decisions on her own too and has a say in the goings-on in the village.” For instance, the sarpanch looked up new games for the village school, and after having seen it on the internet also installed sanitary pad machines in the school.

Alongside, her entrepreneurial spirit continues to drive the women’s collective in Karandi for whom she helps source orders from Pune and other places for their potato chips, with one woman in charge of the accounts and another for quality control. Besides looking up other opportunities for the women online, she is also looking at ways to get a loan for the papad machine that the collective is thinking of buying. The future of work in the digital age can indeed change some age-old idioms.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)