As strange as fiction

Many of the gadgets and technologies that were earlier in the realm of fiction are now present in our workplaces

A still from Elysium

A still from ElysiumImage: Kimberley French

The all-knowing computer

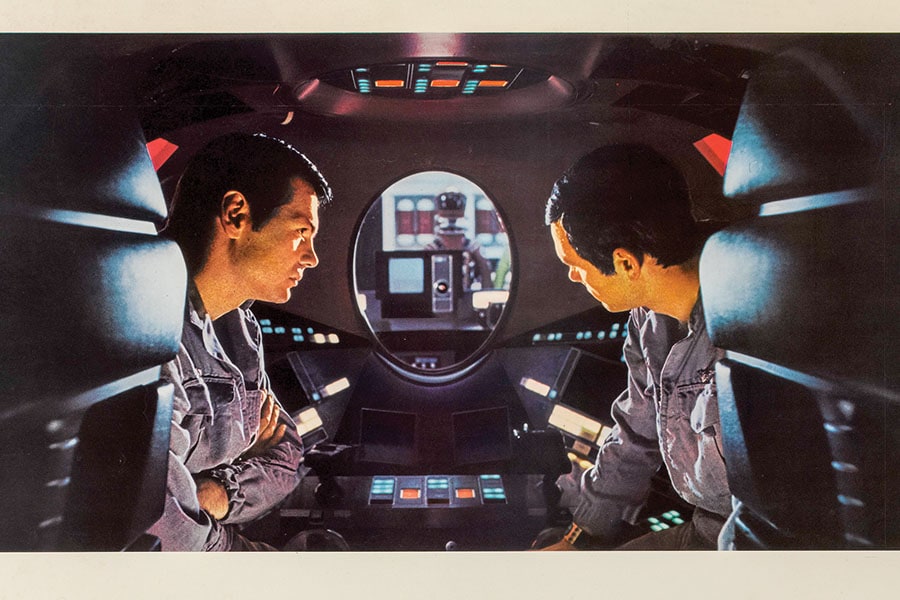

Arthur C Clarke’s HAL, the sentient computer that runs the spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey, is perhaps the ultimate dream of software programmers building artificial intelligence-powered systems. Only if the computer finally does not turn on them, of course, as HAL does on the astronauts aboard the Discovery One, which is headed to Jupiter. The scene, in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film based on the novel, where astronauts David Bowman and Frank Poole enclose themselves in a pod to have a conversation that HAL cannot overhear—but HAL can see them through a glass panel and proceeds to lip-read their conversation—is one of the film’s most chilling.

Today we have software systems that predict whom we want to talk to, even what we want to talk about, administrative systems that know which meeting is taking place in which meeting room, secretarial software that know our week’s schedule better than us, and even cars that know where our office is. We are still far from computers that can do what HAL does, but the possibility of it is becoming ever more potent.

Video calls

In Ridley Scott’s cult classic, Blade Runner (1982), Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) punches in 555-7583 into what looks like a hybrid between a juke box and a telephone booth. Rachel appears on a battered screen, and Deckard asks her out for a drink. Only to be snubbed.

Philip K Dick, on whose book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968) the film was loosely based, set the story in 1992 (2021 in later editions), while Scott based his film in the Los Angeles of 2019.

Video calls over telephone lines, mobile phones, and the internet have, of course, become a reality today with the ubiquity of services such as Skype, and are now used for much more mundane jobs such as office meetings.

Exoskeletons

Over the years, exoskeletons have been depicted in science fiction in various ways, from Sigourney Weaver taking on extraterrestrial monsters with a robotic ‘powerloader’ in Ridely Scott‘s Alien (1979), to Matt Damon having an electronically-powered wearable machine screwed into his bones and head in Neil Blomkamp’s Elysium (2013).

Last year, car manufacturer Ford introduced a pilot programme to test its EksoVest, a wearable contraption attached to the workers’ arms that eases the physical strain of working on an assembly line. On an average these workers lift their hands 4,600 times a day to complete overhead tasks, leading to fatigue and injury. Ford claims the vests support the weight of the workers’ arms, thus putting less strain on shoulders, arms and backs; they also help lift five to 15 pounds of extra weight.

Arthur C Clarke’s HAL, the sentient computer that runs the spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey, is perhaps the ultimate dream of software programmers building artificial intelligence-powered systems. Only if the computer finally does not turn on them, of course, as HAL does on the astronauts aboard the Discovery One, which is headed to Jupiter. The scene, in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film based on the novel, where astronauts David Bowman and Frank Poole enclose themselves in a pod to have a conversation that HAL cannot overhear—but HAL can see them through a glass panel and proceeds to lip-read their conversation—is one of the film’s most chilling.

Today we have software systems that predict whom we want to talk to, even what we want to talk about, administrative systems that know which meeting is taking place in which meeting room, secretarial software that know our week’s schedule better than us, and even cars that know where our office is. We are still far from computers that can do what HAL does, but the possibility of it is becoming ever more potent.

Video calls

In Ridley Scott’s cult classic, Blade Runner (1982), Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) punches in 555-7583 into what looks like a hybrid between a juke box and a telephone booth. Rachel appears on a battered screen, and Deckard asks her out for a drink. Only to be snubbed.

Philip K Dick, on whose book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968) the film was loosely based, set the story in 1992 (2021 in later editions), while Scott based his film in the Los Angeles of 2019.

Video calls over telephone lines, mobile phones, and the internet have, of course, become a reality today with the ubiquity of services such as Skype, and are now used for much more mundane jobs such as office meetings.

Exoskeletons

Over the years, exoskeletons have been depicted in science fiction in various ways, from Sigourney Weaver taking on extraterrestrial monsters with a robotic ‘powerloader’ in Ridely Scott‘s Alien (1979), to Matt Damon having an electronically-powered wearable machine screwed into his bones and head in Neil Blomkamp’s Elysium (2013).

Last year, car manufacturer Ford introduced a pilot programme to test its EksoVest, a wearable contraption attached to the workers’ arms that eases the physical strain of working on an assembly line. On an average these workers lift their hands 4,600 times a day to complete overhead tasks, leading to fatigue and injury. Ford claims the vests support the weight of the workers’ arms, thus putting less strain on shoulders, arms and backs; they also help lift five to 15 pounds of extra weight.

A still from Johnny Mnemonic

Image: Tristar/Getty Images

Image: Tristar/Getty Images

Microchipped humans

Long before Keanu Reeves played Neo in The Matrix trilogy, he was Johnny Mnemonic in 1995, where he plays a man with data storage capacity embedded in his head.His purpose is to carry information that is too sensitive to be stored on computers or physical storage devices.

Although the size of data he carried, at severe risk to life and limb, would appear laughable to us today, the film’s concept of embedded devices is what inspired Swedish company Biohax International to sell and instal chips in human beings. With the national rail company, SJ, as a client, the company has installed chips in the hands of passengers who no longer need to carry tickets in any form; instead, on their daily commute to work, they simply get their hands scanned by the rail conductor.

Could it be long before companies instal GPS-enabled trackers in their employees to figure out if they are really on their way to that meeting, or goofing off at the local bar?

Brain monitoring

In Hirak Rajar Deshe (In The land Of The Diamond King), a 1980 satire against a statist society, Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray depicts a Jantarmantar (a magical gadget) used by an oppressive king to brainwash dissidents. His soldiers routinely round up non-conformists, young students included, who are then thrown into a chamber that rewires their brains and turns them into blinkered loyalists. The tables turn eventually when Goopi Gyne and Bagha Byne, the protagonists, help a rebel teacher topple the king and have him thrown into Jantarmantar.

Long before Keanu Reeves played Neo in The Matrix trilogy, he was Johnny Mnemonic in 1995, where he plays a man with data storage capacity embedded in his head.His purpose is to carry information that is too sensitive to be stored on computers or physical storage devices.

Although the size of data he carried, at severe risk to life and limb, would appear laughable to us today, the film’s concept of embedded devices is what inspired Swedish company Biohax International to sell and instal chips in human beings. With the national rail company, SJ, as a client, the company has installed chips in the hands of passengers who no longer need to carry tickets in any form; instead, on their daily commute to work, they simply get their hands scanned by the rail conductor.

Could it be long before companies instal GPS-enabled trackers in their employees to figure out if they are really on their way to that meeting, or goofing off at the local bar?

Brain monitoring

In Hirak Rajar Deshe (In The land Of The Diamond King), a 1980 satire against a statist society, Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray depicts a Jantarmantar (a magical gadget) used by an oppressive king to brainwash dissidents. His soldiers routinely round up non-conformists, young students included, who are then thrown into a chamber that rewires their brains and turns them into blinkered loyalists. The tables turn eventually when Goopi Gyne and Bagha Byne, the protagonists, help a rebel teacher topple the king and have him thrown into Jantarmantar.

A still from 2001: A Space Odyssey

A still from 2001: A Space OdysseyImage: Movie poster image art/Getty Images

Perhaps nothing as draconian, but employees in China’s Hangzhou Zhongheng Electric Co. wear caps fitted with lightweight, wireless sensors that constantly monitor their brainwaves. The data collected is fed into AI algorithms to detect emotional spikes such as depression, anxiety or rage. The company, which manufactures sophisticated equipment for telecommunication and related industries, claims the use of brain sensors increases the efficiency of workers by manipulating the frequency and duration of break times to reduce mental stress. Employees in key positions can also be moved to less critical tasks if they are detected to be too emotional or stressed. The technology is also used at the State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Company in Hangzhou.

Surveillance

When George Orwell’s 1984 was published in 1949, it was a world still reeling from the effects of World War II. His dystopian novel showed Britain as a province that is controlled by extreme forms of surveillance, which is conducted through ‘telescreens’, or two-way televisions.

The nature of CCTV cameras today is not very different from that of Orwell’s telescreens although their purpose is. Surveillance, however, has taken on far more covert forms, with devices and software to scan and record electronic forms of communication and transactions, and physical movements of humans and vehicles. So, the machines we work on all day know exactly who we are working with, what we are chatting or exchanging emails about, what we have bought from that online sale, or where we are planning to go on holiday.

Surveillance

When George Orwell’s 1984 was published in 1949, it was a world still reeling from the effects of World War II. His dystopian novel showed Britain as a province that is controlled by extreme forms of surveillance, which is conducted through ‘telescreens’, or two-way televisions.

The nature of CCTV cameras today is not very different from that of Orwell’s telescreens although their purpose is. Surveillance, however, has taken on far more covert forms, with devices and software to scan and record electronic forms of communication and transactions, and physical movements of humans and vehicles. So, the machines we work on all day know exactly who we are working with, what we are chatting or exchanging emails about, what we have bought from that online sale, or where we are planning to go on holiday.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X