Travel: A unique tour of a former 'student prison' in Germany

At Heidelberg University, the 'prison' is a glimpse into the fun and philosophy that shaped young minds over many decades

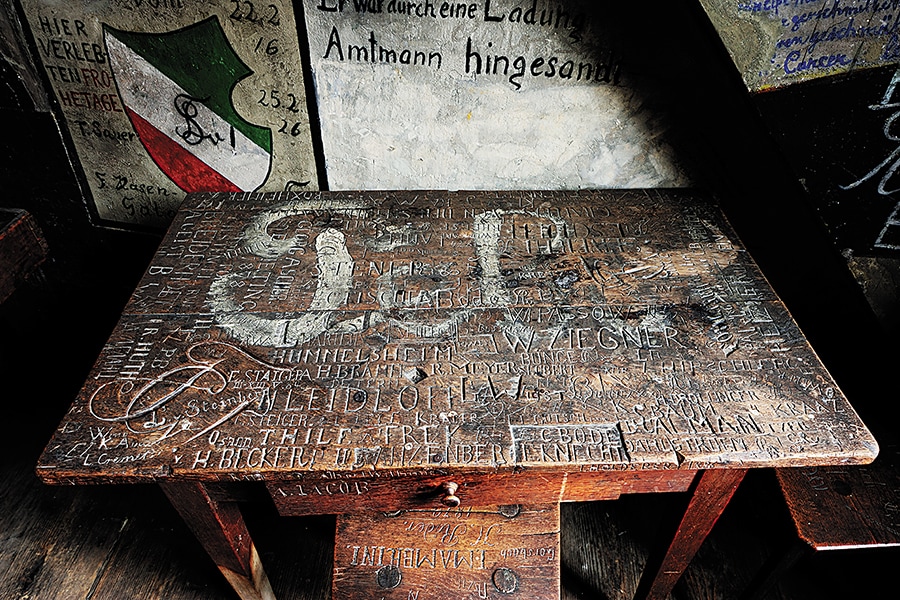

The walls of the student jail at Heidelberg University are covered with drawings and graffiti

The walls of the student jail at Heidelberg University are covered with drawings and graffitiImages: Albert Ceolan/De Agostini Picture Library Via Getty Images

Walking into Heidelberg’s Old Town is like walking into a page of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and half expecting to see a princess climb down from a tower. Half-timbered (wooden frames held together by pegs) and Baroque facades, church spires that tower over clusters of red roofs, and the evocative ruins of a red sandstone castle that looms on the hill, framed by distant forests.

Unlike many German cities, “Heidelberg was not destroyed by bombing in World War II and that’s why so many buildings have remained intact from the Middle Ages and early Renaissance period,” explains our guide Dino Quaas. Down the ages, the city has attracted artists, philosophers and writers, from German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe to American novelist Mark Twain and English painter William Turner. Today the city is well known as a scientific hub, especially for research being conducted at the German Cancer Research Centre.

Through the ages, Heidelberg has been ruled by the Celts and Romans, and then the Palatine Electors of 13th to 18th centuries, powerful princes who were king-makers. It was in this town that the famous jawbone of homo heidelbergensis, the earliest evidence of man in Europe, was discovered in 1907. Today, this city in the Rhine Rift Valley has around 160,000 inhabitants, where one in every four residents is a student. It sprawls over an area of 108 sq km.

What the town is most famous for, however, is its esteemed university, and its students. Established in 1386, Heidelberg is Germany’s oldest university, with as many as 55 Nobel Laureates having studied, taught or worked there. It is also the city’s largest employer.

Panoramic view of the Old Town of Heidelberg

Panoramic view of the Old Town of HeidelbergImage: Werner Otto/Ullstein Bild Via Getty Images

The Heidelberg University sprawls over three campuses today, with the Humanities department located in the University Square of the Old Town. The Old University building was constructed between 1712 and 1728, and has the Rector’s office as well as the University Museum. Close by is the ornate sandstone Renaissance building. Built in 1905, its architecture has elements of Art Nouveau, and it houses the University Library.

On the first floor of the Old University is the Great Hall or the Aula Magna. Dating back to 1886, its awe-inspiring interiors have wood-panelled walls, frescoes and chandeliers. It is still used for concerts, performances and lectures, and is lined with the statues, busts and paintings of people who have contributed to the university over the years. On the ceiling are beautiful frescoes depicting the four faculties of the university: Theology, law, medicine and philosophy.

*****

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Wooden tables in the jail were a canvas for poems, clever epithets and cartoons

Wooden tables in the jail were a canvas for poems, clever epithets and cartoons Assembly hall of the Heidelberg University

Assembly hall of the Heidelberg University