Inside Ebrahim Alkazi's photography collection

With the passing away of Ebrahim Alkazi, we present a glimpse into his collection of late 19th and early 20th century photography, which is a testament to his foresight and finely attuned historical sense

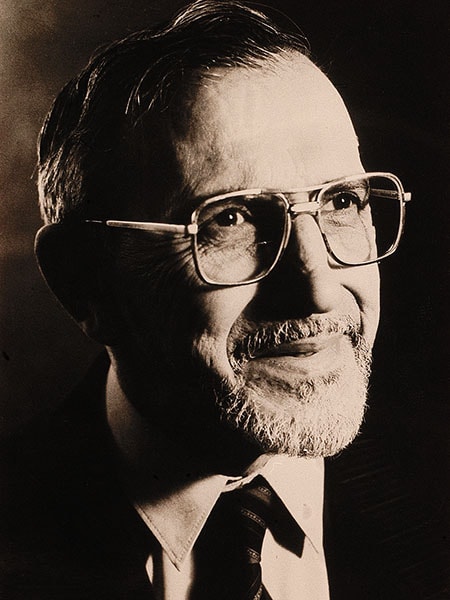

Ebrahim Alkazi

Ebrahim Alkazi All photographs courtesy: The Alkazi Collection Of Photography

"You are ultimately what you are in the darkness of the night in your room thinking of yourself,” Ebrahim Alkazi said to an interviewer in early 1995. “In your utmost loneliness, you realise what you are—just an ordinary being trying to understand life.”

And to understand life, the impulses that trigger one’s actions and the historic underpinnings that lie at the heart of it, was the courageous journey that Alkazi—the son of parents from the Arabian peninsula, who had chosen to settle in Pune—embarked on. He expressed himself through a kind of hybrid, multi-domain practice in the arts, marked by a distinct visual approach to his acclaimed work in theatre. Photography had been a useful tool to document the work he was doing. It was the need to save an important slice of history, which was intertwined with his own, a history linked to issues of identity, race and social structure.

In the late 1970s, Alkazi set out to collect photography, bringing to it his tactile and compelling instinct for value. Alkazi’s first forays as a young student were to the flea markets in London, where he was struck by the knowledgeable dealers at the stalls who sold him postcards and photographs. Slowly, he began to acquire a reputation among them as this bloke who specialised in India photographs. He bought entire albums, which would’ve otherwise been dismantled by the dealers and sold as individual photographs. He went to auction houses such as Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams, finding them expensive and himself ‘too awkward’ to bid for anything, but got an idea of how to look for these photographs. Drawn to photographs that document the Indian subcontinent’s history in certain contexts, he was quoted in Mint as saying he believed “history is a living thing that never dies and unless you make yourself a part of it, you can never really comprehend what it is all about”.

Alkazi’s strength lay in his tireless quest for knowledge, which made him into a walking library of sorts. Often soliciting the help of scholars and historians, he made acquisitions from auction houses, with passion and rigour over three decades, making it one of the largest holdings of 19th and early 20th century photographic prints from South and Southeast Asia, amounting to over 90,000 images. The core of the collection comprises works in the form of photographic albums, single prints, paper negatives and glass plate negatives from India, Burma, Ceylon, Nepal, Afghanistan and Tibet. Almost every region with a history touched by British colonial rule is represented. These vintage prints document sociopolitical life in the subcontinent through the linked fields of history, architecture, anthropology, topography and archaeology, beginning from the 1840s and leading up to the rise of modern India and the Independence Movement of 1947. The collection has now expanded to include contemporary works and the technologies that are used to produce them.

In the wake of the 2001 terror attacks on the World Trade Centre, Alkazi chose to bring his vast collections home from New York and London and house it in a foundation to ensure that his endeavour won’t crumble into anonymity after him. The Alkazi Foundation for the Arts supports scholars to draw on its resources in archiving and curatorial practice, through a series of publications, exhibitions and seminars. Establishing a relationship between painting, photography and performance, the collection has more recently been used for installation pieces that are part of enactments.

Ranging from work by Raja Deen Dayal, one of India’s earliest professional photographers to Homai Vyarawalla, the first Indian woman photojournalist, the archive is, as its curator Rahaab Allana says, “an ongoing process as there are no limits to what it can be”.

A Bengali Couple (c1880-1920)

A Bengali Couple (c1880-1920)Johnston & Hoffman Oil paint on Opalotype, 505 x 380 mm

A rare example of Opalotype— an image handprinted on a type of glass—from a photo studio in Calcutta (now Kolkata), of a couple expressing a certain cosmopolitanism

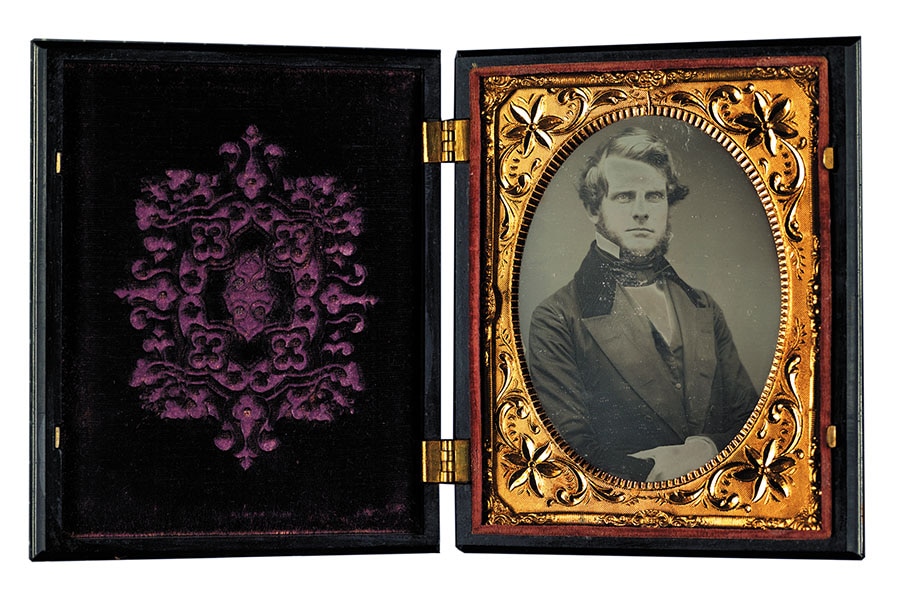

Unknown photographer; Littlefield Parsons & Co (Case Maker) Tinted Daguerreotype, 108 x 82 mm

An early example of a tinted daguerrotype, the first photographic process to arrive in India upon the invention of photography

Anuradhapura, Ceylon, from the album Views of Ceylon (late 1870s)

Skeen & Co [Attributed] Albumen Print, 213 x 271 mm

A striking example of early interest in the picturesque, especially of archaeological sites, using people to define the scale of the monuments

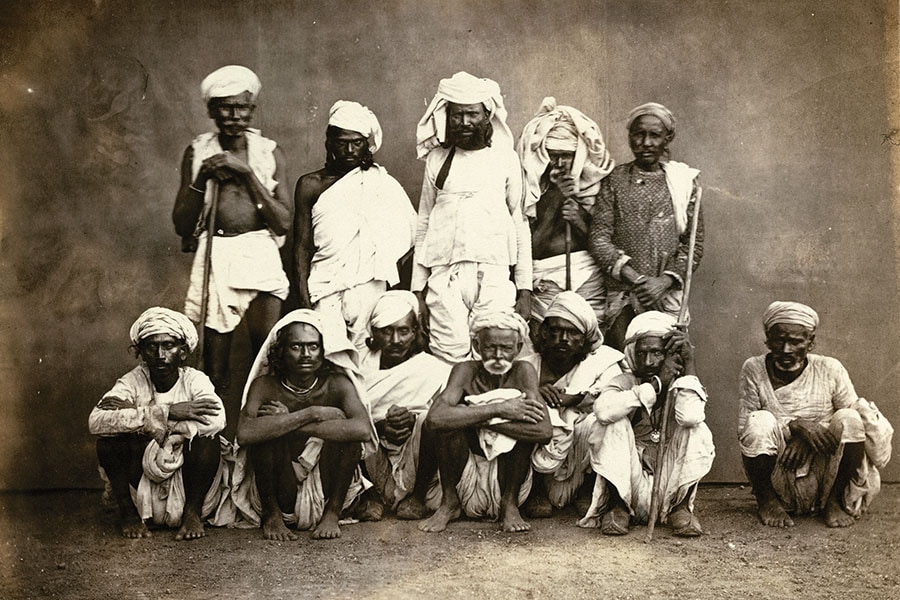

Bheelalahs, Sehore

Bheelalahs, SehoreJames Waterhouse, from The Waterhouse Albums Albumen Prints, c1862

A British soldier, Waterhouse toured extensively through Central Indian provinces on commission from the government, photographing nobles, tribes and archaeological sites

Her Highness the Nawab Secunder Begum, Bhopal

Her Highness the Nawab Secunder Begum, BhopalJames Waterhouse, from The Waterhouse Albums Albumen Prints, c1862

A British soldier, Waterhouse toured extensively through Central Indian provinces on commission from the government, photographing nobles, tribes and archaeological sites

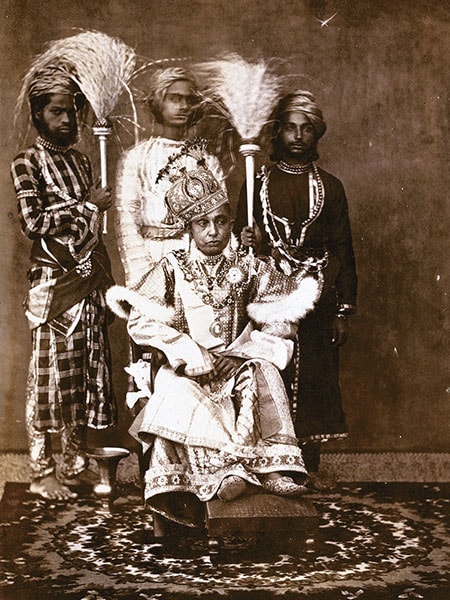

Keshorao Appa Changun (probably at Indore)

Keshorao Appa Changun (probably at Indore)James Waterhouse, from The Waterhouse Albums Albumen Prints, c1862

A British soldier, Waterhouse toured extensively through Central Indian provinces on commission from the government, photographing nobles, tribes and archaeological sites

A Young Tamil Hindu Girl (1890)

A Young Tamil Hindu Girl (1890)Scowen & Co Albumen print, 261 x 250 mm

An early image of a transnational, a young Tamil girl from Ceylon, whose parents had crossed borders to work in the plantations there

A student at the JJ School of Arts, Bombay (now Mumbai), late 1930s

A student at the JJ School of Arts, Bombay (now Mumbai), late 1930sHomai Vyarawalla

An image from Vyarawalla’s early years in Bombay, when her work was featured in advertising and on magazine covers like Illustrated News

Venkatesh Shirodkar, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry (now Puducherry) (1948-1975)

Venkatesh Shirodkar, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry (now Puducherry) (1948-1975)Illusion Gelatin silver print, 245 x 291 mm

An interest in pictorialism and painterly composition marks this image by a student at the school set up by Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1955

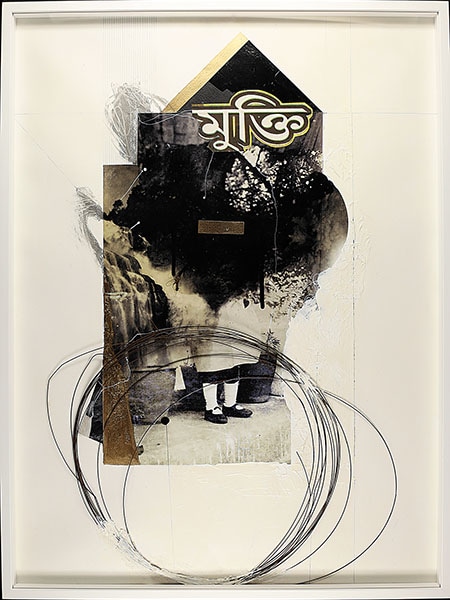

From the series ‘Isometries’ (2018)

Sukanya Ghosh Archival photographs and mixed media

A recent acquisition, this work brings collage-montage-analog practice to the fore, using the artist’s family photo archive to reinvent personal histories

From the series ‘Being Gandhi’ (2016)

From the series ‘Being Gandhi’ (2016)Cop Shiva Hahnemuhle photo rag bright white paper

An image that combines nationalist symbol and performance and its meaning in contemporary times

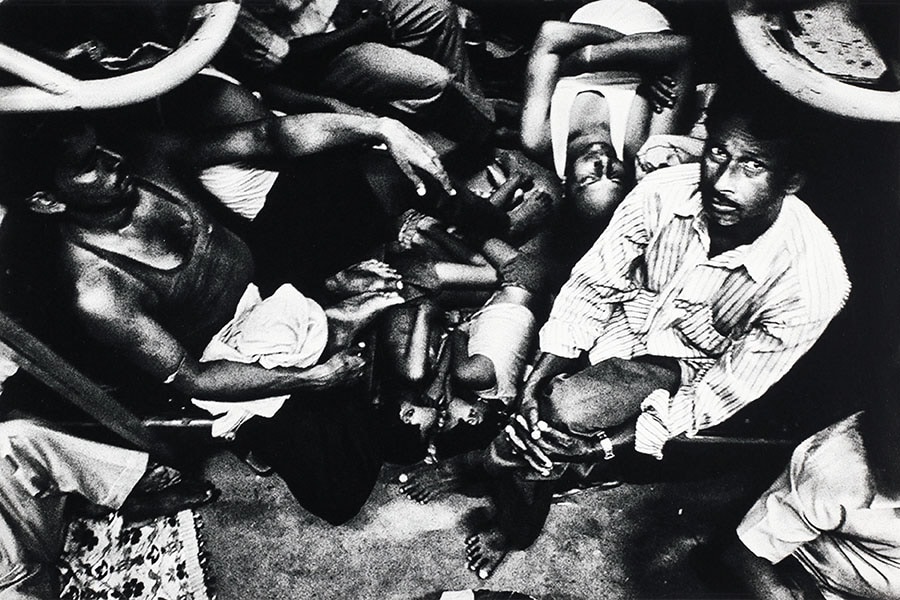

From the series ‘Don’t Breathe’ (2009-10)

From the series ‘Don’t Breathe’ (2009-10)Ronny Sen Digital

The chaos of mass transit and the descent into facelessness is also a metaphor for a citizen’s devalued identity, robbed of belonging