Scripps Networks Interactive Staying True to its Roots

While most cable networks are off chasing the next Honey Boo Boo, Scripps Networks thrills investors by sticking close to home

The home of cable channels Food Network, HGTV and Travel Channel is tucked between the old Brown Squirrel Furniture Store and the Dead Horse Lake Golf Course at the foot of the Great Smoky Mountains in Knoxville, Tennessee. The building curves around a lake where, on pleasant days, employees take meetings in paddle boats. You know you’ve found the right place when you see the big mural of the squirrel.

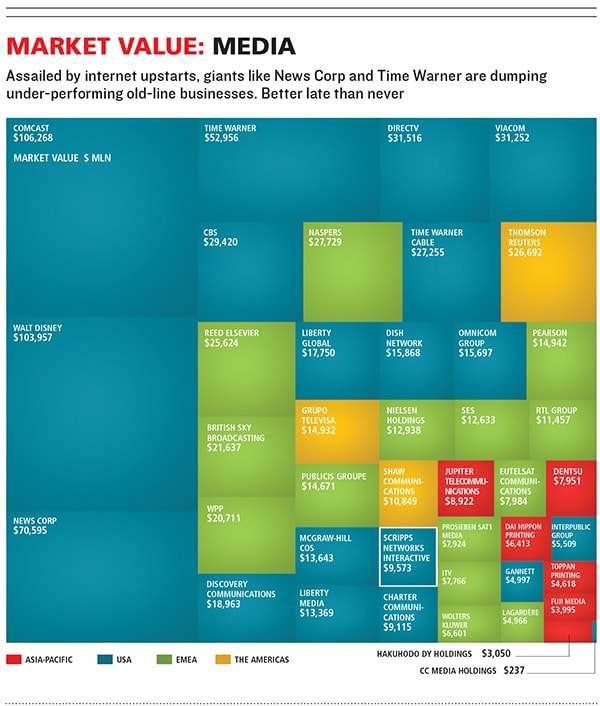

Manhattan media this ain’t, and the folks at Scripps Networks Interactive are just fine with that—as are their investors. Scripps ranks No 1,572 on our Global 2000 list, jumping up 159 spots from last year, and is the best-performing media company on the list based on long- and short-term sales growth, profitability and shareholder return. Over the past five years, revenues at Scripps Networks have increased an average 11 percent per year and net income has increased 50 percent annually. The stock is currently trading at an all-time high of $68 per share. “Food Network has a 57.7 percent cash flow margin,” says Derek Baine, senior analyst at SNL Kagan. “That’s pretty impressive for any company.”

It has succeeded with a radical plan: Staying true to its roots. While ratings at Discovery’s speciously named Learning Channel are driven by shows like Hoarding: Buried Alive and Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, it’s impossible to find a programme on the Food Network that doesn’t deal with cooking. At HGTV, pushing the editorial envelope means a show like Love It or List It, which radically combines buying real estate and home renovation. “When you start chasing ratings and get away from who you are, you’re skating on thin ice,” says Chief Executive Officer Kenneth Lowe, 59.

The network is Lowe’s baby. He started his career running radio stations, and by the early 1990s, he was running nine local affiliate TV stations for newspaper outfit EW Scripps.

A frustrated film director and architect, he had quietly been working on a plan for a cable network focussed on home and garden. He noticed people in their 30s and 40s were talking more about their homes than music and there was no MTV equivalent for the newly settled set.

Lowe pitched his idea to the powers-that-be at Scripps, and they bit. Back in the 1990s, newspapers were flush. The $25 million Lowe needed was paltry. So, in 1994, Lowe launched the new division, installing it in Knoxville (population 180,000) so employees could “live the brand”, tinker with their homes, cook in big kitchens and garden in ample yards.

To persuade cable companies to carry the channel, Lowe offered them retransmission of Scripps’ local networks at a reduced price if the carriers would also take the new home network for a few extra cents. Lowe quickly landed his network in 10 million homes and had to figure out how to fill 24 hours of airtime. Early shows like Wine Cellar and Garden Party aired multiple times a day as Lowe built up his library.

One of the few other lifestyle networks on the air at the time was Food Network, owned by the Providence Journal and a consortium of cable operators. It was extremely sleepy. There was actually a show called How to Boil Water. Worse, Food had signed deals allowing cable providers to carry the network for free for 10 years.

Lowe still saw potential, especially in one of the network’s hosts, a Cajun chef with an outsize personality named Emeril Lagasse. He bought the network—with its dingy Manhattan studio and bad contracts—in 1997 and set about rebuilding. “I don’t even know how we had a health permit,” remembers Lowe.

Lagasse, with his New England charm and catchphrase, “Let’s kick it up a notch!,” was a revelation, drawing crowds—in person and on the small screen. Lowe repeated the pattern, ferreting out talent like Rachael Ray, Bobby Flay and Candice Olson and turning them into household names. Programming was cheap, and cable providers started paying up (Food now commands 18 cents per subscriber per month, HGTV 16 cents, according to SNL Kagan). Advertisers flocked, too. Ad revenue is up 70 percent since 2007 to $1.6 billion.

Not everything went well. In 2001 Lowe launched Fine Living, a channel aimed at an affluent audience. It was announced on September 11. “There was a lot of money there, but the country wasn’t in the mood to celebrate upscale living,” says Lowe. The network limped along until he rebranded it the Cooking Channel in 2010.

Lowe’s biggest challenge now is the Travel Channel. Scripps bought a 65 percent stake from Cox Communications in 2009 for $181 million, outbidding News Corp.

Unlike the Food Network, Travel already had its own stars, including Anthony Bourdain and Adam Richman. Bourdain defected to CNN last year (his new show started on April 14) and took some parting shots at Scripps after the network re-edited footage from his show to make it look like he was endorsing Cadillac. He may have been mad, but he had little recourse for action. While other networks pay a fee to use content from their shows’ production companies, Scripps insists on owning the content, which (as Bourdain acknowledges) gives it the right to edit and reuse the material any way it wants.

There are bigger issues. Right now Travel earns 14 cents per subscriber per month from cable companies, and last year the network brought in $280 million in revenue to HGTV’s $786 million. But Travel has potential internationally. Food Network is available in 85 countries, but outside of that Scripps has been slow to expand overseas. Last year, the company bought UK-based Travel Channel International, and Scripps is starting to produce shows unique to different countries.

That doesn’t mean Lowe is going to alter the formula. Cookin’ with Honey Boo Boo? Not gonna happen. “At the end of the day,” says Lowe, “you have to stand for something.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)