Chief Martin Winterkorn's Best Laid Plan for Volkswagen

Nothing will halt Volkswagen chief Martin Winterkorn’s audacious onslaught of the auto business. Not even Europe’s collapsing economy

It was a blowout. Germany was up 4-0 early in the second half over Sweden at October’s World Cup qualifier in Berlin. Naturally, the team relaxed—and things unravelled. With 28 minutes to play, Sweden scored, then scored again. And again. And again. The Germans had no response. Final score: 4-4.

For Martin Winterkorn, a talented goalkeeper who had professional aspirations and now runs Volkswagen AG, the porous performance was hard to witness. Yet, at a recent management meeting he dimmed the lights, cued the video and made his team watch the nightmare play out again. When the lights came back up, Winterkorn solemnly reminded his people of what they already knew: “It’s halftime.” Five years ago, on the eve of the Great Recession, he had laid out an aggressive plan to land Volkswagen at the top of the global auto industry by 2018, surpassing both General Motors and Toyota. “We’ve had three strong years,” he acknowledged. “You might feel good, but we have to stay focussed.”

His goal is more than just topping GM and Toyota financially. By 2018, Volkswagen will be “the world’s most profitable, fascinating and sustainable automobile manufacturer”, Winterkorn says, with annual sales of 10 million vehicles and a pretax profit margin of 8 percent or higher, compared with the modest 6 percent on sales of 6.2 million cars and trucks worldwide when he took over in 2007. He also intends to have the most satisfied customers and employees (there are 550,000 of the latter worldwide) in the industry. “Only an automaker who can achieve all these goals,” he tells Forbes, “can really call itself number one with justification.”

Sceptics may snicker that Winterkorn’s grandiosity is delusional, especially his plan for the US, where VW would need to triple its 2008 volume to meet his target of one million cars a year (800,000 Volkswagens and 200,000 Audis). Competitors like Toyota, Honda and Hyundai aren’t about to yield; neither will the domestics. VW had ignored the US market for decades after stumbling badly in the 1980s and remains saddled with a reputation for high prices, mediocre quality and a tin ear for American tastes.

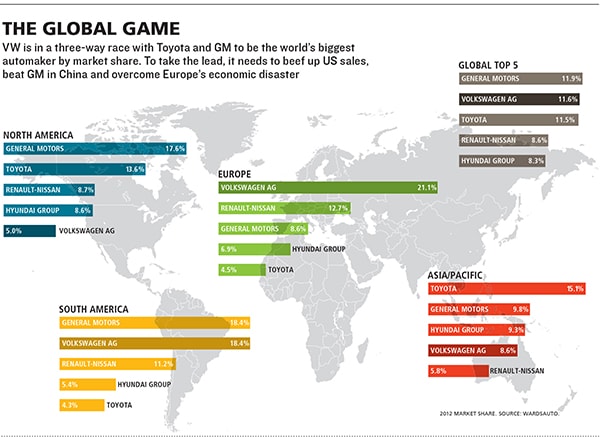

But halfway into Winterkorn’s ambitious strategy, and despite a challenging economy, those 2018 predictions are looking conservative, if anything. Vehicle sales are up 49 percent worldwide since 2008, to 9.3 million units, and its global market share has improved to 12.8 percent, up one-half of 1 percent. Revenues grew even faster (up 63.5 percent), fuelled by strong demand for pricey luxury models from Audi and other premium brands. Europe remains difficult, but Volkswagen is outperforming competitors there. And it has enviable positions in growth markets such as China and Brazil. Even in the US, VW has momentum, with 2012 sales up 31 percent, to 580,000 vehicles (including 438,000 VWs and 139,000 Audis). This all translates into big profits: Last year, VW earned a record 13.2 percent on $250 billion, a performance that makes his long-term forecast of an 8 percent margin look like sandbagging.

To sustain this growth, Winterkorn is deploying this cash gusher towards the biggest spending binge in VW’s history. Over the next two years the company, along with its Chinese joint ventures, plans to invest almost $80 billion in 10 new plants (including seven in China) and scores of new products, from an American-style SUV to a $9,000 starter vehicle for emerging markets, as well as in technologies like plug-in diesel hybrids and advanced infotainment systems.

“Their only vulnerability is themselves,” says automotive analyst Rebecca Lindland of Rebel Three Consulting. “They can be tripped up by arrogance, underestimating their competitors or overspending foolishly.” Neither GM nor Toyota is sitting still. Both are spending about $8 billion a year on research and development, while investing billions more to expand capacity.

That’s why Winterkorn wanted to remind his people what can go wrong if they lose focus midway through the game. In soccer terms, he gives this assessment of VW’s performance so far: “We have completed an extremely successful first half with a strong team and the right strategy. However, one thing is clear: Conditions on the pitch are deteriorating. Pressure is growing.”

“Volkswagen must continue to attack and make good use of its opportunities,” he continues. “Then we will still be ahead when the final whistle blows.”

To fully understand the scope of Winterkorn’s ambitions, it helps to go to VW’s hometown of Wolfsburg, Germany, a small northern city in the middle of nowhere that literally grew up with the Volkswagen Beetle. The city was carved out of farmland in 1938 as a place to house workers assembling “the people’s car” ordered up by Hitler prior to World War II. Until the massive factory with its imposing power plant was erected along the shores of the Mittelland Canal, the most notable landmark was the medieval Wolfsburg Castle, for which the town was named.

Today Wolfsburg (population 123,000) might as well be called Volkswagen City. The 73-million-square-foot factory, employing more than 50,000 workers, and an adjacent 13-storey brick headquarters building still dominate the riverfront landscape. The company’s influence is everywhere, from VW-sponsored cultural festivals hosted in a defunct power plant to the nearby Volkswagen Arena, home of the VW-owned VfL Wolfsburg soccer team, to the VW-owned Ritz-Carlton hotel, where visiting VIPs tend to stay.

But nowhere is VW’s ambition more on display than at Autostadt, the $1.2 billion Epcot-like theme park across the river from the sprawling factory.

Some 2.3 million visitors a year stroll the park’s 69 acres of lagoons and rolling hills or visit the famous ZeitHaus, the most popular car museum in the world. An interactive, multimedia exhibit lets visitors explore the latest developments in areas like vehicle design or sustainability. Some just come for the VW-made currywurst, a popular fast-food sausage with curry-flavored ketchup.

About one-quarter of the tourists are Volkswagen customers who travel from all over Europe—sometimes even farther—to take delivery of their Wolfsburg-built vehicles. Last year, Volkswagen delivered more than 173,000 new vehicles this way, instead of at the dealerships where they were sold.

The cars awaiting delivery each day are stored in one of two iconic 20-storey glass towers that rise above the Wolfsburg landscape. Robotic elevators pluck 500 cars a day from their sky-high perches and present them to their waiting owners down below. Even people who aren’t buying a car can get a feel for the process in a stomach-churning ride to the top in a glass elevator. I buckled into one of a half-dozen seats and held my breath as we climbed past a rainbow of shiny new Golfs, Tiguans and other cars, looking over the entire Volkswagen empire—the factory, one of the largest in the world; the headquarters in the distance; the swooping, white Porsche pavilion (Autostadt’s latest addition) directly below; and the soccer arena across the highway.

It’s a flashy marketing tool for Volkswagen’s kingdom of car brands, which are showcased in museum-like pavilions within the park. Besides VW itself, there is Audi, Porsche, Lamborghini, Bentley, Bugatti, Ducati, SEAT, Skoda, MAN, Scania and Volkswagen Commercial Vehicles, most of which are multibillion-dollar businesses in their own right. As a whole VW works as an automotive conglomerate, with each semi-autonomous unit funnelling profits from sales of 280 different models back to the mother ship, fuelling Winterkorn’s ambitions.

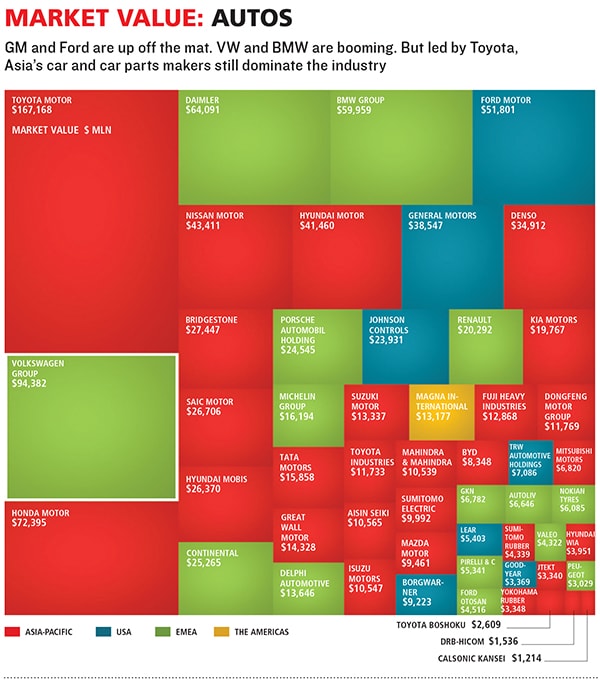

While mass-market cars and financial services constituted almost 60 percent of VW profits as recently as 2007, Winterkorn has nearly reversed that—more than half its earnings now comes from premium brands. Trucks are also a big factor here. Until 2000, Volkswagen wasn’t a big player, selling mostly smaller commercial trucks under the VW brand. But when Volvo Trucks’ 1999 attempted takeover of fellow Swedish truckmaker Scania failed to win regulatory approval, Volkswagen swooped in and bought Volvo’s share. Winterkorn bought the remainder from Investor AB in March 2008. In 2012, VW repeated the trick to gain control of Germany’s MAN, another heavy truck company. As a result, heavy trucks will soon account for 17 percent of earnings before interest and taxes, says Deutsche Bank analyst Jochen Gehrke, while the efficiency resulting from combining purchasing and product-development efforts could yield $1.7 billion in savings. Suddenly, VW’s truck division rivals that of Daimler AG.

Porsche is even more important. VW and Porsche share a history: They were founded by rival branches of the Porsche family. But this permanent coupling began in an unusual way: Early in Winterkorn’s tenure, the sports carmaker, seeing the synergies, tried unsuccessfully to swallow the much-larger VW. Riddled with debt as a result of that effort, Porsche wound up selling to Volkswagen: First a 49.9 percent stake in late 2009; then last summer, after clearing various legal hurdles, VW acquired the balance for $5.7 billion.

In Porsche, Winterkorn’s effort to move VW past the people’s car mission that Hitler envisioned for it finally has a crown jewel and one that he can expand behind the full weight of the parent. Gehrke expects Porsche to generate $2.5 billion in operating profit, which is a margin of 18 percent—the most profitable auto company in the world. Winterkorn is shifting Porsche, once purely a sports car outfit, into a premium luxury brand, with upcoming models like the Macan compact sport utility, a midsize sedan similar to the BMW 5-series and a 2+2 coupe designed to take on Ferrari.

As with the trucks, Winterkorn is to marry surging revenues with waste reduction. His biggest initiative: A new modular “tool-kit assembly” system that will allow the company to build all of its vehicles, from the smallest Skoda to the most luxurious Bentley, using just four basic tool kits—one for small city cars, one for midsize cars, one for sports cars and one for large cars and SUVs. Other carmakers have found similar efficiencies by putting different “top hats” on common engineering platforms. VW boasts that this system will go far past that, standardising the engine position and the distance between the gas pedal and front wheels on every car, where 60 percent of development costs are incurred, allowing the rest of the vehicle to be stretched in any direction: Thus it’s easy to build different-size vehicles using shared components or to swap diesel, hybrid or electric drivetrains for a gasoline engine, depending on consumer demand. The new VW Golf and Audi A3, for example, are the first of about 40 new small and midsize models that will be developed using the small-car tool kit.

This modular approach will in large part determine whether VW can pass Toyota or GM. There’s big risk here: If something goes wrong with a shared component, the problem can quickly multiply across VW’s entire lineup. Just ask Toyota, which was forced to recall millions of vehicles worldwide to deal with quality issues in a handful of faulty parts. “There’s an example of where plans went horribly awry,” says Rebel Three’s Lindland. And Audi and VW don’t exactly have stellar reputations for quality. Both brands rank below average on quality and vehicle dependability in JD Power & Associates’ studies. The upside, though, is tantalising: If it works as it should, modular assembly, VW says, will save at least 20 percent a year in car costs and shorten assembly times by 30 percent.

Winterkorn, born outside Stuttgart in 1947, a decade after the birth of the company he now runs, came of age as VW did, when it rose from the ashes of World War II. With a doctorate in metal research, he worked for the industrial giant Robert Bosch in the late 1970s until 1981, when he was lured to Audi by Ferdinand Piech, the Volkswagen Group chief who would become his mentor for the next 25 years.

He arrived just in time for some of the worst years in VW’s history, the result of a previous generation’s mismanaged global ambitions. In 1978, VW took over a former Chrysler factory in New Stanton, Pennsylvania, and officials confidently predicted that the company would soon grab 5 percent of the US car market. By early 1980, VW had 5,700 employees in Pennsylvania and was producing 200,000 Rabbit small cars a year.

But that incursion onto US soil ended badly. The clunky Rabbit missed the mark with consumers, as small cars from Toyota and Honda proved more reliable and popular. Even after introducing the Jetta in late 1986, the plant was operating at less than 40 percent of capacity. In July 1988, VW closed it for good and shipped the equipment to China. The ’80s were also tough for Audi, which suffered a massive blow after reports of unintended acceleration in its cars. But 1987 also marked the beginning of VW’s strong growth in China. By the late 1990s, VW’s brand image had moved upmarket, and its portfolio was growing with the addition of Skoda, Lamborghini and Bentley.

Winterkorn worked in a variety of quality and production roles at VW and Audi, earning a reputation as a boss who obsesses about the tiniest product details. By 2000, he was named to the parent company’s board, overseeing research and development for the entire group and, in 2002, Piech made him chief of Audi.

His success at Audi, a key profit engine, propelled him to his current position. He succeeded Bernd Pischetsrieder, who had the job only four years before falling out of favour with the still powerful Piech, now chairman of Volkswagen AG’s supervisory board.

Piech and Winterkorn have been called Germany’s “dream team” because of their complementary leadership talents. There’s no question that the mercurial Piech, 76, is still calling the shots strategically. He is the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, developer of the fabled sports cars and inventor of the VW Beetle, and his family still controls about 30 percent of VW’s shares and 53 percent of its voting rights. While group chief executive, Piech started the collection of luxury brands under the Volkswagen umbrella.

Winterkorn, methodical and precise, is now carrying out Piech’s vision. Wiko, as he’s known, differs from other auto industry executives presiding over far-flung empires, however. Unlike Renault-Nissan Chief Carlos Ghosn or Chrysler-Fiat boss Sergio Marchionne, he is a classic car guy. “Winterkorn is very product-focussed. He lets others run the financial show,” says Christoph Stuermer, an analyst at IHS Automotive. “He’d rather kick the financial guys to do some magic to make sure he can still build the best car possible.”

He’s been known to throw production schedules into chaos by ordering last-minute engineering changes. Shortly before Lamborghini was set to introduce the new Aventador superluxury sports car in 2011, for instance, Winterkorn took the 690-horsepower behemoth for a final test drive. After racing around the track at speeds close to 200 miles per hour, he told engineers the instrument panel on the $387,000 sports car had to go. He made them rip out the dashboard and redo it, resulting in a six-month launch delay. Winterkorn isn’t apologetic. “I have always been driven by the ambition to solve every problem I face,” he says. “The main things are dedication to the task at hand and consistency in performance.”

Before the launch of the redesigned VW Passat in 2011, Winterkorn flew to Chattanooga, Tennessee, seven times to inspect the vehicle’s quality. When it was unveiled at a press event, Winterkorn was furious after discovering a tiny paint flaw on one of the media test-drive cars, according to one colleague. At the Frankfurt Motor Show in 2011, he was caught on video poring over a new Hyundai model, griping to one of his engineers that the Koreans managed to cheaply design a steering column adjuster that made little noise, yet VW could not.

Often blunt and sometimes gruff, Winterkorn’s supreme confidence can be mistaken for arrogance. “We are a team, and we have a very clear, common goal,” says Christian Klingler, board member for sales and marketing. “There are a lot of debates about how to achieve it. But he’s a brilliant boss, and you are learning from him every day.” Stuermer has a less pc way of putting it: “He doesn’t like bad news. Before anyone reports to him, they make sure they have good news.”

Pity VW’s heads of China and Brazil, respectively, given how their boss operates. VW has such dominant positions there that bad news will follow a downturn in either of those BRIC nations. Karl-Thomas Neumann, VW’s head of China operations, was pushed out last year, partly because of an embarrassing quality problem with new gearboxes in its cars. VW has a different kind of problem in India, where a failed partnership with Suzuki, whose affiliate Maruti Suzuki has almost half of the Indian market, left the German automaker on its own to develop cheap cars for emerging markets. It hasn’t gone so well: VW’s market share sits below 5 percent.

Things don’t look much better at home. Europe’s weak economies have soured consumers on the idea of buying a car for the foreseeable future, leading to the lowest industry sales there since 1996. The crisis gripping Europe’s industry is similar to the one that bankrupted GM and Chrysler in 2009: There are too many factories and not enough demand. But amid political resistance to cutbacks, it’s been tough to close factories or cut jobs. So carmakers keep cranking out vehicles and selling them at a loss. Winterkorn terms 2013 “a year of truth for the entire industry”. His 280-model brand diversity and broad geographic footprint leave him well-positioned for this year of truth. Some rivals, notably Chrysler-Fiat boss Marchionne, have accused Volkswagen of creating a “bloodbath” by offering aggressive discounts to gain market share during the downturn. While VW says it plans to hold prices steady, “They can always add more features, or they can work with the financing guys to subsidise loans,” says Stuermer. “That way, they can really create some havoc with competitors.”

In a nod to that tactic, Winterkorn predicts that while VW’s revenues will continue to march upward this year, profits will remain at 2012 levels. To him it’s simply gamesmanship. Soccer, after all, remains more than a metaphor. Most weekends he can be found in his usual spot—Row 7, Seat 6—in the VIP section at Volkswagen Arena, cheering on the local team, nicknamed the Wolves. “I am an emotional person, and soccer is sheer emotion,” he says. “For me, it is the best way to unwind.” He is joined at every game by Bernd Osterloh, the powerful union chief who also serves as Piech’s deputy on the Supervisory Board.

During halftime, at one recent game, fans milled around the giant buffet tables on the suite level, loading their plates with currywurst, pretzels and other stadium fare. Winterkorn sat with his back to the field sipping wine with Osterloh and others. He seemed happy. But was he? The Wolves trailed 1-0. His team still had work to do.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)