Can Novartis Chief Joseph Jimenez Cure Cancer?

With a radical new treatment, Joseph Jimenez is dedicating Novartis to one overarching mission: Vanquishing mankind's ancient adversary. Its breakthrough might be the most tangible... ever

For 85 percent of kids with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chemotherapy is a cure—but not for Emily Whitehead, 6. Diagnosed at 5, she got an infection from her first round of chemo and nearly lost her legs. Then the cancer came back; she was put into remission and scheduled for a bone marrow transplant. As she waited, the cancer returned yet again. There was nothing else to try.

Nothing except a crazy experimental treatment never before given to a child: Blood was taken out of Emily’s body, passed through a machine to remove white cells and put back in. Scientists at the University of Pennsylvania used a modified HIV virus to genetically reprogram the white cells so that they would attack her cancer, and reinjected them.

But the cells attacked her body, too. Within days Emily was so feverish she had to be hospitalised. She was sent to the intensive care unit and put on a ventilator. A doctor told her family that there was only a one-in-1,000 chance she would survive the night. Then the miracle breakthrough: Doctors gave Emily a rheumatoid arthritis drug that stopped the immune system storm—without protecting the cancer. Emily awoke on her 7th birthday and slowly recovered. A week later her bone marrow was checked.

Emily’s father remembers getting the call from her doctor, Stephan Grupp: “It worked. She’s cancer free.”

She still is, two years later—taking piano lessons, wrestling with her dog and loving school, which she couldn’t attend while sick. “I’ve been an oncologist for 20 years,” says Grupp, “and I have never, ever seen anything like this.” Emily has become the poster child for a radical new treatment that Novartis, the third-biggest drug company on the Forbes Global 2000, is making one of the top priorities in its $9.9 billion R&D budget. “I’ve told the team that resources are not an issue. Speed is the issue,” says Novartis Chief Executive Joseph Jimenez, 54. “I want to hear what it takes to run this phase III trial and to get this to market. You’re talking about patients who are about to die. The pain of having to turn patients away is such that we are going as fast as we can and not letting resources get in the way.”

A successful trial would prove a milestone in the fight against the cancer. Coupled with the exploding capabilities of DNA-sequencing machines that can unlock genetic code, recent drugs have delivered stunning results in lung cancer, melanoma and other deadly tumours, sometimes making them disappear entirely—albeit temporarily. Just last year the Food & Drug Administration approved nine targeted cancer drugs. It’s big business, too. According to data provider IMS Health, spending on oncology drugs was $91 billion last year, triple what it was in 2003.

But the developments at Penn point, tantalisingly, to something more, something that would rank among the great milestones in the history of mankind: A true cure. Of 25 children and five adults with ALL, 27 had a complete remission, in which cancer becomes undetectable. “It’s a stunning breakthrough,” says Sally Church, of drug development advisor Icarus Consultants. Says Crystal Mackall, who is developing similar treatments at the National Cancer Institute: “It really is a revolution. This is going to open the door for all sorts of cell-based and gene therapy for all kinds of disease because it’s going to demonstrate that it’s economically viable.”

There are still huge hurdles ahead: Novartis has to run clinical trials in both kids and adults around the world, ready a plant to create individualised treatments and figure out how to limit side effects. But Novartis forecasts all that work will be done by 2016, when it files with the FDA.

Progress like this explains why Jimenez is focusing his pharmaceutical giant on a simple mission: Cure cancer. Cancer drugs represent $11.2 billion of Novartis’ $58 billion in annual sales, but he says he’s “doubling down” on the cancer business. In April he did a deal that essentially traded Novartis’ unprofitable vaccine and consumer businesses and up to $9 billion in cash to GlaxoSmithKline in return for Glaxo’s cancer drugs, which generate $1.6 billion in sales but which Jimenez says include three pills he can turn into $1 billion sellers. The same day, he sold his veterinary business to Eli Lilly. He calls it “precision M&A”—bartering for the divisions you want, instead of bidding $100 billion for an other rival, as Pfizer is doing with AstraZeneca. Jimenez’s move, which he terms “the antithesis of megamergers”, will drop Novartis’ 2016 sales 5 percent but boost earnings per share (before extraordinary items) by 10 percent, according to investment bank Jefferies.

Jimenez has competition: Seattle-based Juno Therapeutics, which counts Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos among its backers. But that’s to be expected when the potential is so staggering—and tangible. “Anybody that gets associated with this technology and sees what this technology has been able to do really believes they’re participating in something that’s historic,” says Jimenez. “I look at it and think about the potential breakthrough that it could be. You could be looking at a transformation of the treatment of cancer over the next 20 to 30 years.”

Jimenez seems an unlikely backer for one of the most revolutionary medical breakthroughs any company has ever tried to develop. He’s a marketer who, until he came to Novartis in 2007, managed brands like Clorox and Peter Pan Peanut Butter before running the North America business for Heinz. But a seat on the board of AstraZeneca got him interested in selling products that saved people’s lives. He was brought in to run Novartis’ $4 billion consumer products division, home to Triaminic and Theraflu, was rapidly promoted to run drug marketing and, in a surprise to everyone, made the chief executive.

Jimenez’s predecessor, Daniel Vasella, saw in him someone who could pilot Novartis through what was going to be a tough time. On Jimenez’s watch, manufacturing problems temporarily shut plants in consumer and animal health. By leaning on its generic-drug business, the world’s second largest, and its eyecare division, Alcon, Jimenez kept sales and earnings stable, at $58 billion and $9 billion. Novartis benefited from a 33 percent stake in rival Roche, with $31 billion in oncology sales. He fixed the plants, and Novartis’ stock has outperformed the S&P 500 over five years—a total return of 176 percent versus 139 percent—and outpaced the American Stock Exchange’s pharmaceutical index.

But Jimenez’s job wasn’t just to make numbers, it was to protect a legacy. Vasella’s proudest moment was the decision to ignore his own marketing people and instead listen to an Oregon oncologist named Brian Druker, who was begging him to develop a cancer drug called Gleevec. Gleevec became a breakthrough, helping almost every patient with a particular rare blood cancer, chronic myelogenous leukemia. Patients stay on it for years, and it is so valuable that Novartis has quadrupled its annual price from $24,000 per year in 2001 to more than $90,000 today. Even the stingiest insurers pay, though some patients get it free.

What the marketers thought was a $400 million drug, Jimenez notes, is now a $4.6 billion one, and Novartis’ top seller. The lesson: Worrying about marketing, instead of whether drugs work, is bad for business. “We keep our commercial people away from key decisions that are being made in research at an early stage,” Jimenez says. “Whereas another company might have commercial people in there looking at business opportunity or market size, we have said we don’t want that.”

Gleevec literally changed the architecture of the company’s Basel headquarters. A drab manufacturing campus was reimagined like a college, with sidewalk cafes, benches to facilitate conversations and a glass building designed by Frank Gehry. Vasella moved its research headquarters to Cambridge, Massachusetts, a block from MIT.

Unfortunately for Novartis, the patent for Gleevec could expire as soon as July 2015. And lately Novartis’ R&D has lagged; in the decade before Jimenez took over the company launched 16 drugs, more than any other company, according to consultancy InnoThink, but in the four years since it has managed only one a year, half as many as Johnson & Johnson. Worse, it seemed to Jimenez that Novartis H&M was missing out on a new vanguard of drugs Bristol-Myers Squibb was pioneering that used the immune system as a weapon against tumours.

“We’re behind the leaders here,” Jimenez says. He worries that his scientists have taken too much to heart another lesson from Gleevec, that understanding the bio-chemical mechanisms behind a drug is essential. Instead, he says, sometimes you just have to say: “This works, and we better jump in.”

Everything changed for Novartis with a patient named Douglas Olson, then 64, who had been diagnosed 14 years before with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. His disease no longer responded to chemo, and he had two years to live without a risky bone marrow transplant. Then he got the cell treatment that Novartis would soon buy. He spiked a fever of 103 and had to be hospitalised because his kidneys were failing. His kidneys made it, but the cancer didn’t. Five pounds of cancer cells disappeared from his blood and bone marrow. “I had a complete mind shift. All of a sudden you don’t have this thing sitting there waiting to kill you.” He bought a boat and, four years later, still cancer free, scheduled an interview with Forbes around chainsawing trees on his Pennsylvania property.

Olson’s result was published, without his name, in the New England Journal of Medicine in August 2011. Data from two other patients were published at the same time in Science Translational Medicine. “The phone started ringing off the hook with people wanting to start companies and all sorts of venture capitalists and all that,” says Carl June, the Penn researcher whose team developed the therapy and who three years before couldn’t raise money around it. “Then we had three Big Pharmas coming. It was incredible how it happened.”

All three companies—two still unnamed because of confidentiality agreements— offered the same cookie-cutter financial terms: $20 million up front, with a royalty on sales and milestone payments paid to Penn. June gets only a pittance compared to what he would get if he’d started a bio-tech, but he says he doesn’t care. The bio-tech route would be too slow.

Novartis made a full-court press. R&D head Mark Fishman came personally—he knew June’s boss, Penn medical school dean J Larry Jameson, early in their medical careers. The personal history helped. June also knew Barbara Weber, Novartis’ head of translational medicine, and Novartis scientist Seth Ettenberg had trained with June and shared his sense of mission—Ettenberg went into cancer research because his brother had died of leukemia. June, like Fishman, likes to talk about curing cancer as his goal. But what really sold June was the story of Gleevec. Novartis already knew blood cancers, and it knew breakthroughs, and that was good enough for him.

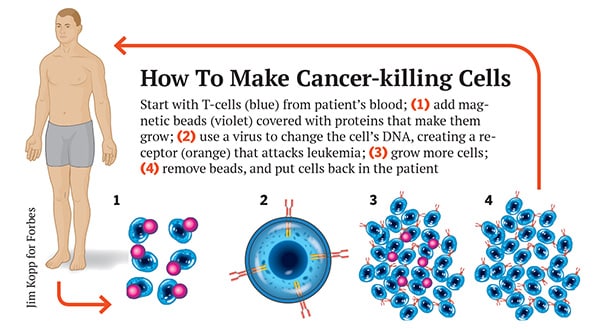

But commercialising June’s cancer-killing cells would be like no drug development programme ever. Scientists call them chimeric antigen receptor T-cells, or CARTs. T-cells are the immune system’s most vicious hunters. They use their receptors to feel around in the body for cells with particular proteins on their surface and destroy them, targeting infected cells and cancer. With CARTs scientists add a manmade receptor—the chimeric antigen receptor—assembled from mouse antibodies and receptor fragments. A gene code for the manmade receptor is inserted into the T-cell’s DNA with a virus, usually a modified HIV. If the receptor sees cancer, not only does it kill it, it starts dividing, creating a cancer-killing army.

Downsides: “So far, it’s only blood cancer, it’s high technology, it’s customised therapy, it’s going to require major investment,” warns Clifford Hudis, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, who is nonetheless excited about the cells. The current CARTs kill not just cancer cells but any B-cell, the type of white blood cell that goes wrong in leukemia. Patients are likely to get injections of a protein that B-cells make, called gamma globulin, for the rest of their lives; if the treatment becomes popular there may not be enough gamma globulin to go around.

First comes the challenge of figuring out how to deliver a personalised therapy to patients with ALL. Their blood will need to be filtered at hospitals, then sent to Novartis, then sent back. How do you manage that? Luckily, one biotech, Dendreon, solved this problem with its prostate cancer treatment, Provenge. Even luckier for Novartis, Provenge was not that effective and flopped, and Dendreon was looking to offload a manufacturing plant. Novartis gave Dendreon $43 million and kept 100 of the plant’s 300 employees. In fact, its treatment will be easier to manage than Provenge: The T-cells can be shipped frozen; Provenge couldn’t. Bruce Levine, tasked with growing cells at Penn, says the facility is a dream come true. “The results are there, the science is there,” he says. “It’s an engineering issue.”

Getting approved is the easy part. Will CARTs work for all cancers? Targeted drugs like Gleevec are more effective against blood cancers than solid tumours like lung or breast cancer; the same thing may be true with CARTs. Even going from Emily’s disease, acute leukemia, to the chronic leukemia Doug Olson had, the rate of complete remission drops from 90 to 50 percent.

“It’s a little early to know whether or not the remarkable results we’re seeing will show us whether these are the drugs we’ve been looking for or whether these are the first powerful signals that we’re headed in the right direction,” says Louis M Weiner, the director of Georgetown University’s Lombardi Cancer Center. Though the cells are “amazing”, says Charles Sawyers, the past president of the American Association for Cancer Research and a Novartis board member, “what we don’t know is how broadly does this scale?” Penn and Novartis will soon begin studies in mesothelioma, a lung cancer, to start answering that question.

Then there is the problem of competition. June, Novartis’ partner, wasn’t the only one to think of using CARTs to attack cancer, just the first to publish evidence that it could work. But others were on the same trail, and most of them pooled their efforts into a bio-tech: Seattle’s Juno Therapeutics.

Juno was the brainchild of Larry Corey, the director at “the Hutch”—the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, perhaps the centre of research into how the immune system keeps cancer in check. Richard Klausner, former head of NCI, helped find backers: ARCH Venture Partners and the Alaska Permanent Fund, and then others, including Bezos, who have together put in $175 million, perhaps the largest Series A round ever in bio-tech.

The reason for the excitement: Six of the top researchers in the CART field, from the Hutch and elsewhere, have banded together to produce the next generation of cancer-killing cells. “We want to be a $50 billion market cap company that cures people,” says ARCH partner Robert Nelsen. While Novartis bought one of Dendreon’s plants, Juno hired the man who built them: Former Dendreon CEO Hans Bishop, 50. “I’ve just never seen early clinical data like this,” he says. “I’ve been in this industry a long time and been in clinical development a long time, and the things we see are as different as night and day.”

In February co-founder Michel Sadelain of Memorial Sloan Kettering published data in acute leukemia that rivals that of Novartis: His CARTs induced a complete remission in 18 of 21 adults. And then there are other Juno CARTs created in Seattle, with miracle stories like that of Milton Wright III, 20. He got ALL at 8, but his cancer came back twice, five years apart. He’s handsome and fit but with heart problems from chemo. The third time, he was offered CART therapy, which was followed by high fevers, low blood pressure, a disappearance of cancer and a bone marrow transplant.

A next-generation CART method being developed at the Hutch by Juno seems to cause less severe fevers. Juno has another option: A T-cell that uses natural receptors to detect cancer. It will mix and match to create even better CARTs.

There’s already an ethical battle brewing. Juno and other CART researchers say they are ethically bound to offer patients bone marrow transplants, which, though often fatal, are proven cures; so far, many patients from Novartis and June’s studies are not doing this. Penn researchers say many of their patients are not eligible for transplant and that, in some, their CARTs seem to work for years.

Other competitors include an unpartnered CART programme at MD Anderson Cancer Center and another from Kite Pharma, which has paired with NCI immunology pioneer Steven Rosenberg, and a third from bio-tech giant Celgene, which is working with tiny Bluebird Bio. “You look at a company like Celgene, and you know they’re going to figure it out,” Jimenez says. “And they should figure it out. It will be good for patients. We want to beat the competition, but we’re really using the competition to trigger us to get to the patient.”

Despite the promise presented by the treatment, Jimenez says, the biggest hurdle in developing new cancer cures might be economics, not science. “What you know is not going to happen is the ability to stack therapies on top of each other at the current price and expect people to pay,” he says. “The whole oncology pricing structure needs to be rethought because it’s reached the level that is not going to be sustainable for the long term.”

This is actually what’s driving his strategy of bulking up his cancer division—so it can compete—and at the same time betting on the wildest technology. He expects “a new brutal world” for health care companies as countries around the world are forced to double health care spending because of age and illness over the next 10 years. Paradoxically, the rapid increase in costs will lead governments to try to cut costs, making competition between hospitals, doctors and drug companies tougher.

“You’re going to see these companies that are going to get crushed by this new environment, despite the fact that health care spending is going to almost double,” Jimenez says. He has a team exploring ways of pricing cancer drugs, in which several medicines are sold for the price of one, or health systems or insurers pay based on how many patients are cured.

When researchers talk about CARTs they often reference the cost of a bone marrow transplant—$350,000 for a single course of treatment. Why not? There are bio-tech drugs for rare diseases that cost $400,000 or more a year. But Jimenez says that would be too much—that even for a breakthrough the cost needs to be lower.

Earlier this year Novartis bought its way into the field of immune-stimulating cancer drugs by purchasing CoStim for an undisclosed price, figuring it needed to combine them with its targeted pills and CARTs.

It’s also the force behind his Glaxo deal, getting rid of unprofitable divisions and giving him volume to negotiate with the drug buyers of the future: Governments and insurance companies.

He met Glaxo CEO Andrew Witty at meetings of the European pharma trade group. They started talking about vaccines and quickly realised that each had businesses the other wanted. They had to push the complicated deal through their companies.

Among the toughest points was making sure Novartis will have opt-out rights for the consumer health joint venture they created, which Glaxo will control, if things go sour.

Can Novartis deliver? The company that topped the pack when it came to new drugs a decade ago now ranks 18th out of 22 in a new analysis by Sector & Sovereign Research that ranks drug companies based on the economic returns of their R&D. But things are turning, with not only the cancer drug but a pair of heart medicines that may become blockbusters. As Gleevec showed, it takes only one drug to change a company.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)