Asian Paints: Riding the Indian Middle Class

Asian Paints has decorated India’s walls and ceilings for decades. Its secret? A loyal rural base, smart use of technology and a fixation on customer service

If you wanted to have a paint company, you’d want to be in an industrialising country, where millions were joining the middle class and buying their first homes. And you would have started it decades ago, lining up paint dealers in every town so you’d have a lock on the market when the country takes off. To keep your head start, you’d obsess about customer service, stay on top of technology and hire managers trained at the best schools. This is how Asian Paints came to dominate the walls and ceilings of India, creating three billionaires along the way.

Asian Paints started in 1942, reached the top of the Indian market in 1967 and has stayed there ever since. It now sells through 35,000 dealers across India. Over the last five years its revenue has nearly doubled, to $2 billion for the year ended March 31. Profits have more than doubled over the same period, to $205 million for that year. And the stock has jumped 140 percent since August 2008, giving it a market capitalisation of $6.3 billion.

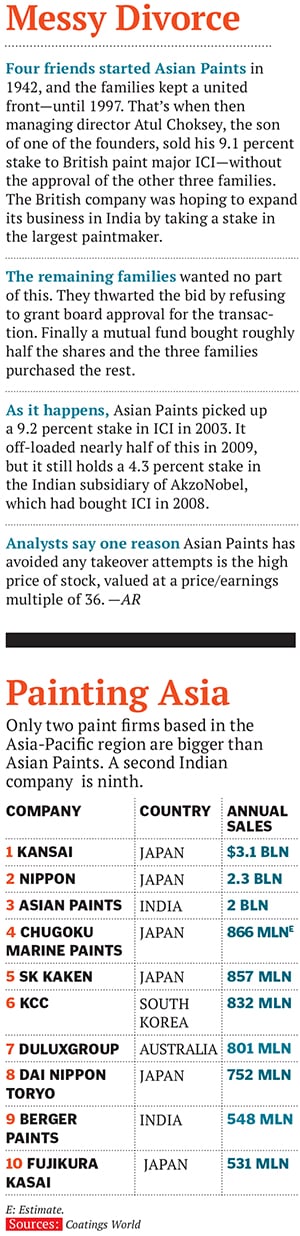

It ’s now Asia’s third-largest paint company, behind Japan’s Kansai and Nippon (see table), and the world’s 13th largest. This year it appears on the Fab 50 for the third time in a row. “The company knows its customers well,” says Adrian Lim, senior investment manager at Aberdeen Asset Management, a UK firm that owns 1.6 percent of Asian Paints. “It has resilient business plans, healthy cash flows and a strong balance sheet.”

The Mumbai company—which sells paint and similar products—has been refashioning itself into a home decor company, hoping to benefit from India’s soaring urbanisation. “There’s been a massive transformation in the Indian consumer,” says KBS Anand, Asian Paints’s managing director and chief executive. “Earlier, people used to paint when the walls were peeling. Now it’s about decor.”

To capitalise on the trend, the company launched a premium range of paint in 2004 called Royale Play. Each paint adds a different special effect to interior walls, lending them a metallic luster, a soft sheen or a stucco finish, for example.

Stores too have gone upmarket. In 2009 the company introduced dealer-owned Colour Idea stores and now has 100 of them. Unlike traditional dealers who sell through hardware stores, the new stores focus on matching customers to the right colour.

They’re outfitted with boards displaying samples of interior and exterior finishes, and there’s a consultant who provides computer visuals showing how a room will look when painted. Asian Paints also runs two high-end showcase stores, in Mumbai and New Delhi. These don’t sell any paint, but have walls of displays showing various shades and textures under different light settings.

The company’s four founders sure weren’t thinking signature stores when they began making paint during World War II. With the war curtailing paint imports, Suryakant Dani, Champaklal Choksey, Chimanlal Choksi and Arvind Vakil decided to make paint locally. Today Asian Paints does business in 17 countries in the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, the Caribbean and the South Pacific, and operates 25 paintmaking plants—10 in India and 15 overseas.

Descendants of three of the four founders—the Danis, Choksis and Vakils—own more than half the company, each with fortunes crossing $1 billion. The Chokseys exited in the late 1990s.

Anand, 58, took charge in April 2012 and is now spearheading three initiatives: A foray into the home improvement segment, bolstering the industrial paint division and boosting the international business. Last month Asian Paints bought a 51 percent stake, for $20 million, in Indian kitchen company Sleek International, which sells modular kitchens and kitchen accessories. “This is an aligned business,” says Anand. “The basic customer is the same—the homeowner. Eventually we want to be in all areas of home improvement.”

With industrial paint Asian Paints last year forged a second joint venture with the US’s PPG to make industrial coatings, which include floor coatings and road markings. (The first JV was in 1997 for automotive coatings.) Industrial paint comprises only 6 percent of revenue, but is important for diversification.

As for the international business, which contributes 13 percent of revenue, the company is looking to do more business in emerging markets such as Bangladesh and Nepal—and in the Middle East, which supplies half its overseas revenue. It wants 25 percent of revenue to come from international operations eventually.

Back in India, the economy has been slowing for three years. Another challenge is the falling rupee, because the company imports most of its raw materials. It raised prices by 5 percent last year and has announced three price hikes for this fiscal year.

Company executives are philosophical about the slowdown. “If the economy doesn’t grow [faster] and purchasing power is reduced, I don’t think paint is the most important thing that you’ll buy,” agrees Anand, who has seen many down cycles in his 34-year stint. “We’ll have to learn to live with lower growth.”

But the long-term story is solid. India’s urban areas are expected to gain 200 million people by 2030, meaning more construction and more paint. The Indian market certainly has room to grow: Annual paint consumption is 1.9 kilos a person, as opposed to 5.5 kilos for the Asia-Pacific region. Consumption in rural areas is growing even faster, and that’s where the company has long been the strongest—Asian Paints wooed small shopkeepers in villages and tiny towns early on because foreign companies dominated paint sales in the cities.

“When everybody was concentrating on urban markets, they realised that there could be a big rural market,” says NK Bhatia, a past president of the Indian Paint Association. Even the colours Asian Paints made were a nod to what rural India wanted—dark aquamarine or deep daffodil, because dark shades were considered to be powerful.

Loyal dealers form the backbone of Asian Paints. Take S Muralidharan, who has been a dealer for 25 years, selling to builders and retailers in Chennai. “We get lots of customers because of Asian Paints’s brand image and the quality,” he says. “The service is good, the supply is good, and the dealers are taken care of.” The company has nearly three times the number of dealers as Berger Paints—India’s second-largest paintmaker—and adds 1,000 to 2,000 every year.

Asian Paints certainly found itself well positioned when the boom came, but it didn’t blow its lead. Nomura Securities notes that in the past decade the company has gained market share. One strategy was to find more ways to stay close to its customers. In the late 1990s it started a customer helpline, which now gets 2,000 calls a month. It offers home-painting services in 13 cities—an employee comes to a home, sizes up the job, brings in painters who cover up the furniture and do the work.

It sent out Happy Painting Guides to 300,000 customers last year. It provides colour consultancies, in which an employee with interior-design training comes to the home to suggest what can be done for the walls. It trains 8,000 painters a year in two-day workshops to ensure they apply its premium paint in the right way.

Customer interaction leads to insights: It has started offering 200 ml samples of its premium paint at a nominal price, allowing a customer to paint a swath of a wall to see how the colour will look—a significant improvement over the shade card.

Asian Paints’ pioneering use of technology has also been critical to its growth. It bought its first mainframe computer in the 1970s, when computers were virtually unheard of in India. Soon it began using computers to forecast demand and improve the supply chain.

It introduced computerised colour-matching in the mid-1970s. There were PCs in branches by the early 1980s. Today it dishes out a free paint app for smartphones. “A key factor in Asian Paints coming out ahead of the competition is the significantly better supply chain it had, which allowed the company to service a much larger number of dealers than the competition,” says Manish Jain, research analyst at Nomura’s Mumbai office.

Analysts also say Asian Paints understood early on the importance of a good management team. It started hiring from premier engineering and business schools in the 1960s.

Anand himself holds an engineering degree from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, and a diploma in management from the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta. The son of a Navy officer, he was hired off campus in 1979 and has done everything from running a paint factory and handling labour negotiations to leading the decorative business.

These days Anand has his eyes on the competition. All the major players in the $5.3 billion Indian paint market are expanding capacity and seeking to boost market share. Kolkata-based Berger aims to double its revenue in the next five years to top $1 billion; it bought the Indian decorative paint business of US paint company Sherwin Williams in March. Kansai Nerolac, the third-largest Indian paintmaker and a wholly owned subsidiary of Kansai, has raised its capacity by 25 percent in the past year.

The world’s largest paint com- pany, the Netherlands’ AkzoNobel, entered India in 2008 with its purchase of British paint major ICI and plans to reach $1.3 billion in annual revenue by 2018.

“The multinationals are seeing a slowdown everywhere, so everyone’s going to try things in India,” says Anand. “Competition, while already stiff, will get stiffer.” But the competition notwithstand- ing, “Asian Paints appears to have figured out how to grow ahead of the market,” says Nomura’s Jain.

“We expect it to maintain its leadership in the long term.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)