Amritanshu Khaitan: Recharging Eveready

Armed with a sound balance sheet, the MD is leveraging his company's strong brand and distribution network to grow its business beyond batteries

Amritanshu Khaitan, managing director of Eveready Industries India, believes in organic growth, even if it is at a slower pace

Image: Debarshi Sarkar for Forbes India

Image: Debarshi Sarkar for Forbes India

We haven’t done justice to the Eveready brand over the last 110 years,” says Amritanshu Khaitan, managing director of Eveready Industries India, famous for its dry cell batteries and flashlights.

Khaitan’s candid yet curious admission is characteristic of the 33-year-old’s straightforward and to-the-point manner of speaking, as well as his approach towards business. His statement is interesting because 700 million Indian consumers use Eveready products every year and the company is a leader in the organised market for batteries in India with a 50 percent-plus share. What’s more, its extensive distribution network, through which it reaches 3.2 million outlets across India, is only marginally smaller than the 3.6 million outlets covered by fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) major Marico.

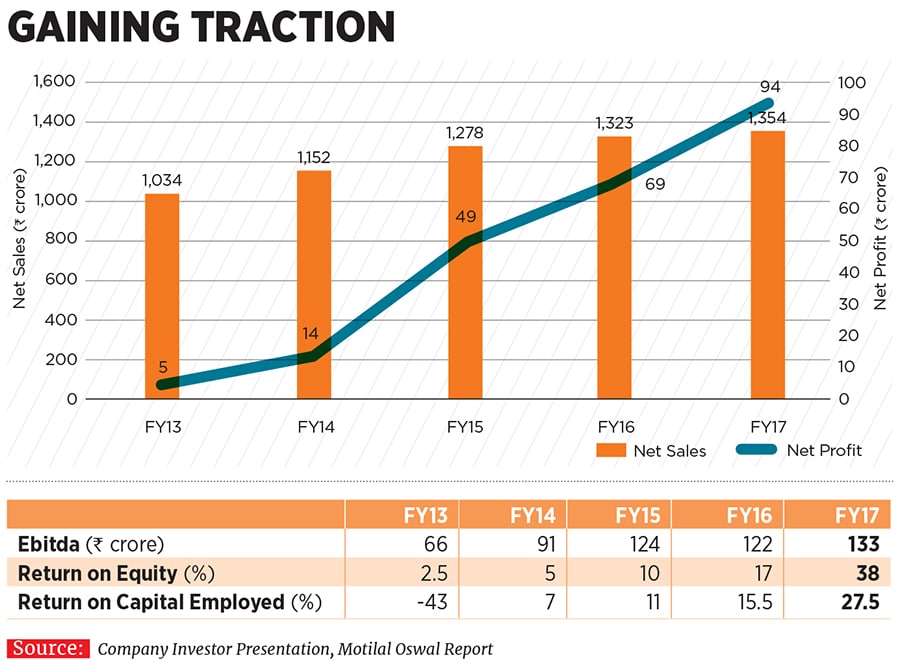

So how has justice not been done to the brand? We are sitting in the company’s headquarters in south Kolkata’s upscale neighbourhood of Rainey Park and Khaitan, a third-generation business leader from the Khaitan family—led by patriarch Brij Mohan Khaitan—explains. According to him, though Eveready has, for over a century, been a powerful and trustworthy consumer brand in India (promoted through iconic ad campaigns like ‘Give Me Red’), restricting itself largely to the Rs 1,500-crore dry cell battery market has meant that even after exploiting its maximum potential in this segment, the scope for future growth remained limited. For fiscal 2017, Eveready, a part of the Williamson Magor (WM) Group (whose businesses range from tea and engineering to consumer goods) reported net sales of Rs1,354 crore, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7 percent since fiscal 2013.

This lack of scale that is purportedly inhibiting the Eveready brand from realising its true potential is what Khaitan—son of Eveready’s former chief Deepak Khaitan, who died in 2015—has set out to rectify since assuming the corner office at Eveready in 2013.

Brand Advantage

The idea is to take the company’s biggest assets—a powerful brand and a deep distribution network —and leverage them to the hilt. Consequently, after batteries and battery-powered flashlights, Eveready has, over the last couple of years, expanded its portfolio of products to include lighting solutions such as LED bulbs and household electric appliances like fans, mixer-and- grinders, and ovens. In June, the company also announced its intention to form an equity joint venture with another group firm, McLeod Russel, to jointly procure and market packet tea under the Eveready brand. By getting into these new businesses, Eveready seeks to expand the field in which it plays to an addressable market size of Rs30,000 crore, 20 times bigger than the traditional battery market in which it leads.

“We did some research to see where the Eveready brand can fit in. We found lighting was a logical first step and there are some great examples of what other companies have done in this space,” says Khaitan. “I have no qualms in admitting that Havells India is a great case study of how the Gupta family has taken the company from being a wire manufacturer to where it is today.”

Founded in 1983 by Qimat Rai Gupta (and currently led by his son Anil Rai Gupta) as a wire maker, Havells India has metamorphosed into a sizeable homegrown electrical appliances company—making everything from fans to LED bulbs to personal grooming products—with a turnover of Rs 6,135 crore.

Balance Sheet Repair

Along with expanding the scope of its operations, Khaitan has also been working on fixing the company’s balance sheet. For instance, a process of demerger in 2004 whereby the bulk tea and battery businesses were housed under separate entities (McLeod Russel and Eveready respectively) led to a significant quantum of goodwill and debt on Eveready’s books. According to Khaitan, this goodwill, under Indian GAAP accounting norms, amounted to around Rs430 crore and the amortisation of this intangible asset over a period of time kept Eveready’s return ratios “artificially” depressed. The company decided to write off this goodwill recently against its general reserves and this led to a dramatic improvement in its key financial metrics.

In 2015-16, Eveready reported a modest return on equity (RoE) of 9.8 percent and a return on capital employed (RoCE) of 10.4 percent. Post the write-off of goodwill, the company’s RoE has improved to 37.7 percent, and RoCE to 27.5 percent.

Between fiscals 2013 and 2017, the company’s bottomline, too, improved considerably—from a reported net profit of Rs5.1 crore in FY13 to Rs93.5 crore in the last fiscal, a CAGR of close to 107 percent. Improved cash flow from operations have also helped Eveready pare debt. A net debt of Rs276 crore in 2012-13 has come down to Rs196 crore in 2016-17. The resultant debt-to-equity ratio of the company has improved to 0.68 from 1.41 in the same period; while the debt service coverage ratio has gone up from 0.52 to 0.65.

Measured Approach

A fund manager with a large mutual fund house that is invested in Eveready says Khaitan has done well to identify the issues that needed to be addressed following the demerger in 2004, which had led to Eveready’s balance sheet getting bloated.

“Amritanshu has age on his side and has shown maturity as a leader,” the fund manager, who did not wish to be named, says. “As a long-term investor in a company, we always look for someone who can be at the helm of affairs for the next 20-30 years and help in value creation.”

Considering Deepak Khaitan was one of the most well-known figures in Kolkata’s business circles, comparisons between the father and son’s leadership styles are inevitable. In Khaitan’s own assessment, his father and he were united in their belief in the Eveready brand and the premium it commands. “As a businessman, he was hungry for growth and keen on acquisitions. This is where I differ. I feel if we can grow organically, albeit at a slightly slower pace, it is a much better option. But if an acquisition opportunity presents itself at the right time, we shouldn’t shy away,” says Khaitan, who lives in a joint family with his grandfather and uncle, Aditya Khaitan, and their families.

Aditya Khaitan, a director on Eveready’s board and managing director of McLeod Russel, the group’s tea business, agrees that his nephew has more patience than his brother, who was more aggressive. “Amritanshu wants to consolidate and grow the business as well as focus on streamlining operations, which is the right way to go,” he says.

The market appears to have believed in the Eveready growth story. From fiscal 2012 till date, Eveready’s market capitalisation has soared over 25-fold to Rs2,571 crore. The Eveready stock has also garnered greater attention from foreign institutional investors (FII) in the recent past, with FIIs hiking their stake by as much as 7.7 percentage points in the January-March quarter alone, to 23.4 percent.

As Eveready seeks to replicate the success of larger peers such as Havells, investors may be sensing a buying opportunity in the company’s stock as it trades at a much lower price to earnings per share multiple than the latter.

700 million Indian consumers use Eveready products every year. For fY17, it reported net sales of Rs1,354 crore, a CAGR of 7% since FY13

A Bigger Play

While Eveready has achieved much, there is still a lot more to be done. Khaitan wanted to clean up the company’s balance sheet at the earliest possible and he says that objective was met on March 31, 2017. The focus is now on growing some of the newer businesses to a larger scale.

The LED lighting business, which they got into in 2015, reported a turnover of Rs200 crore in FY17, double from the preceding fiscal. This includes a government business of Rs50 crore. The plan for FY18 is to double the Rs150-crore turnover realised from retail sales of LED lights as well as enter new segments such as professional lighting. This business vertical turned in a profit in FY17 and is expected to add more meaningfully to the company’s bottomline in the coming years. “We think a 6-7 percent share of a market (the retail market is estimated to be worth Rs6,000 crore and the professional market another Rs5,200 crore) that is growing at more than 50 percent is substantial,” Khaitan tells Forbes India.

“The potential in LED lighting is significant as the government lays greater emphasis on energy-efficient lighting, and the technology shifts from CFL to LED lights,” says Pankaj Tibrewal, senior vice president and equity fund manager at Kotak Asset Management. “Brands that have a strong distribution reach and high quality products will do well in this segment. But bulbs alone won’t be sufficient to sustain growth in this space. Companies will need to sell high quality fixtures as well to differentiate themselves.”

Then there is the appliances business, which they got into in 2016. For FY18, Khaitan says he is looking at a modest turnover of Rs100 crore from this business, at which level it will break even. “I haven’t set a very stiff target for this business yet since the space is very crowded and we will need to make more investments. We are testing the market at present and seeing which categories fit well with our brand before taking a larger leap,” says Khaitan.

Tibrewal says with low penetration of electrical appliances across Indian households, the growth opportunity in appliances is a derivative of the electrification drive in the country. “As more households receive stable electricity supply, they will consume more such appliances. There is room for at least five to six companies with strong brand recall to exist in this space.”

According to Aditya Khaitan, 60-65 percent of the company’s revenues can come from these new businesses over the next five to 10 years.

But do the relatively thin profit margins generally seen in businesses like LED lights and electrical appliances (both crowded markets) make it worth Eveready’s efforts to explore them? Khaitan thinks so. “Our core business (batteries and flashlights) is highly profitable and takes care of most of our overheads,” he says. “So even if margins are lower in the lighting business, the flow-through of profits to the bottomline will be very good. All that we need is economies of scale.”

While the battery and flashlights business contributes most to the company’s turnover and profits at present, there are challenges there to deal with as well. Import of cheap batteries from China—in the absence of any anti-dumping duties—that are sold through the unorganised market, coupled with the effects of demonetisation in the last fiscal, have led to subdued growth.

But steps like demonetisation and introduction of the Goods and Services Tax will help curb the unorganised market, improving the outlook for organised players like Eveready, says Khaitan. As a result, the company isn’t shying away from incurring capital expenditure to increase capacity in this business and has invested Rs100 crore for a new battery-making facility in Assam.

Khaitan also wants to leverage Eveready’s brand appeal and distribution network to expand its presence in the FMCG space. While the firm had a small packet tea business (accounting for 5 percent of its revenues), it wants to make a bigger dent in that market, estimated to be worth Rs10,000 crore. “We can scale up our packet tea business to at least Rs250-300 crore from where it is today,” according to Khaitan.

For this purpose, Eveready and McLeod Russel will be forging a joint venture that will procure and market packaged tea. It is also the first time that two WM Group companies will be exploring cross-synergies. Eveready stands to benefit from McLeod Russel’s expertise in the tea procurement and manufacturing process while the venture presents a new business opportunity for McLeod Russel—the world’s largest tea producer and exporter—in the domestic, branded tea market. If the distribution channel accepts Eveready’s packet tea, it may be utilised to sell some other FMCG products, which can either be branded Eveready or belong to other brands looking to enter India.

Khaitan clearly has ambitious plans for Eveready, the company acquired by his grandfather from the US owners of what was then known as Union Carbide India in 1994. Over the next three to four years, he expects Eveready’s turnover to grow at a CAGR of 15-20 percent, and growth in profitability to be even better than that.

“The whole puzzle has been put into place,” says Khaitan at the start of this interview. And the picture that finally appears looks promising.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X