The state of liberal arts education in India

Colleges offering these courses in India have begun to gain ground, but for them to truly shine on the global map, they must be cognisant of the country's culture and challenges

At Ashoka University in Haryana, one can choose from 21 major and 18 minor courses

At Ashoka University in Haryana, one can choose from 21 major and 18 minor coursesAcademician Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s resignation from Haryana-based Ashoka University in March not only resulted in protests by students, but also put the spotlight on universities that offer them the option of getting a well-rounded and expansive intellectual grounding in all kinds of humanistic inquiry—in the form of a liberal arts degree.

Though specialised liberal arts colleges in India are still relatively young—most of them were established only about a decade ago—they are increasingly becoming popular and beginning to gain a wider student base.

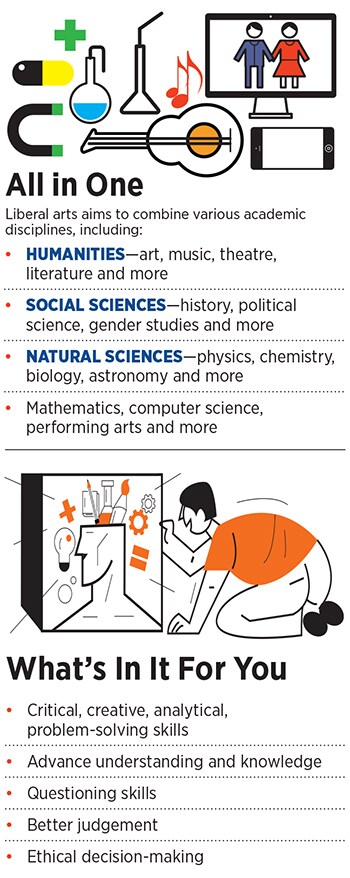

Liberal arts courses are designed to introduce students to four areas of study—arts, humanities, natural and social sciences—and enable them to critically evaluate the environment around them. According to the draft National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 document, “A liberal arts education enables one to truly develop both sides of the brain—the creative and analytical side.”

How, not what

Courses under the umbrella of liberal arts are designed with a multi-faceted approach to challenge students’ understanding beyond their lived experiences. They are focussed on the ‘how’ rather than on ‘what’.

“Students are not taught what to think, but how to think,” says Dishan Kamdar, vice chancellor of Pune-based Flame University. “Such a learning system helps students develop abilities to connect the dots, hone a creative mindset, and inculcate skills to think out of the ordinary”.

Flame University has seen a spike in the number of students opting for liberal arts courses

Flame University has seen a spike in the number of students opting for liberal arts coursesThe development of skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving and adaptability makes liberal arts even more important in today’s times given the fact that for several decades, the Indian education system has focussed on early specialisation and encouraged rote learning.

“This has resulted in a majority of the graduates coming out of our education system not being employable as they lack the requisite skill sets for 21st century jobs,” says professor Malabika Sarkar, vice chancellor, Ashoka University. “Liberal arts’ focus on all-round development and in shaping students’ intellectual, aesthetic, social, physical and emotional capacities not only equips students for a career but also for life.”

Every liberal arts college provides an opportunity to combine multiple academic interests into a single degree programme ranging from arts and performance, communication and design, to history, economics and even international relations.

At Ashoka University, a not-for-profit university and a philanthropic initiative that has raised over ₹1,100 crore in the past eight years through 119 individual and 27 corporate founders, students can choose from a range of 21 majors and 18 minors while making it mandatory to opt for two co-curricular courses.

The Shiv Nadar University allows students to specialise in a subject while experimenting with other electives

The Shiv Nadar University allows students to specialise in a subject while experimenting with other electivesAt Delhi-NCR-based Shiv Nadar University, too, the course is designed to allow students to specialise in a particular subject while studying and experimenting with a wide range of other elective subjects. “Our programmes are designed to strengthen the learner’s foundation or core with a broad multidisciplinary approach and provide depth of learning in a major subject. While there is flexibility in the curriculum, an equal focus is laid on academic rigour,” says Dr Rupamanjari Ghosh, vice chancellor of Shiv Nadar University. The university, funded by the Shiv Nadar Foundation to the tune of $300 million, started in 2011.

Slow, steady growth

In the past few years, the awareness of liberal arts education has increased considerably, say academicians.

For instance, Bengaluru-based Azim Premji University, which began by offering two postgraduate programmes in 2011, currently operates 11 degree programmes and 30 short-term courses across the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Mumbai-based Jyoti Dalal School of Liberal Arts (JDSoLA), established in 2016, started with a batch of 60 students; today it has 120.

“During our recent admission drive, we received applications that exceeded the size of the current batch by more than 10 times, a clear indication of the rising demand for liberal arts education. We expect the demand to rise exponentially in the coming years,” says Dr Achyut Vaze, dean and academic advisor, JDSoLA, SVKM’s NMIMS.

Shivali Padmanabh, 25, who completed her liberal arts undergraduate course in 2017 from Pandit Deendayal Energy University, Gujarat, recalls it was a new concept when she signed up for it. “When I was looking for options for my undergraduate degree, I was looking for a holistic approach over any specialised degree. Liberal arts back then was a rather new concept,” she says, adding that since her graduation she has noticed a considerable increase in the number of students per batch in her university.

“Applications have grown manifold in the last few years, with higher growth seen from international boards and from students who have taken international entrance tests like the SAT or ACT,” says Kamdar of Flame University, a private philanthropic initiative that receives funding through grants. “Our incoming class has more than doubled in the last few years.”

One of the factors behind the growing popularity, say experts, may have to do with the faculty chosen. At JDSoLA, candidates need to have a PhD or an MA and six to seven years of industry experience in the specialised area. Selection is done after several rounds of rigorous interviews, and once selected, they go through intensive training, informs Dr Vaze.

At Azim Premji University, says the registrar Manoj P, “We look for deep and sound disciplinary expertise.” After multiple rounds of interactions, including campus visits, the faculty’s abilities are also gauged on the basis of their display of passion for teaching, and more importantly, an openness to engage with a learning community beyond their disciplinary boundaries.

Another factor that might have worked in favour of these universities is that they are increasingly opting for foreign collaborations to stay true to their idea of exposure. Many foreign universities—from the best in business schools to Ivy League Universities—have signed MoUs with universities like Ashoka, Azim Premji, and NMIMS in India, which ensure that international professors visit these universities for classes/sessions. Some of them also offer exchange programmes.

What the future holds

The NEP 2020 envisions academic disciplines beyond the ‘professional versus liberal education’ binary with recommendations on de-compartmentalising Indian education. While technical institutions will be asked to integrate their curriculum with arts and humanities, students in the latter will have the option to study more science and vocational subjects.

However, one of the biggest concerns about liberal arts education is about its future prospects, meaning how and what the degree could lead to, especially because these three- to four-year courses can cost anywhere between ₹4 lakh and ₹10 lakh a year.

Dr Neeti Sethi, Chair programmes, and professor of liberal arts courses at Thapar School of Liberal Arts and Sciences, in Patiala, Punjab, points out that while the purpose of liberal arts education is much beyond just securing a job, getting a job is not something that can be completely ignored since many students might have educational loans to pay off.

Besides, parents still struggle to fit such courses in the ideal educational path they imagine for their children. “There is a lot of interest for such courses in India but that comes mostly from students, not parents. People from my generation rarely understand the significance of liberal arts,” adds Sethi. This, she says, might also have to do with the limited number of degree options while growing up.

But all this seems to be changing. A 2017 Dell Technologies report predicted that 85 percent of the jobs of 2030 have not been invented yet. In this context, liberal arts universities believe that the jobs of the 21st century will require a capacity to think critically, read discerningly, write persuasively, and be conscious of the impact of one’s actions on society and environment.

“In my experience of studying higher education trends, I’ve seen that liberal arts courses are still misconstrued as not an equivalent of their mainstream counterparts. Majorly so because of the narrative of securing a decent job as the outcome of enrolling in a degree. This is slowly changing as students focus on education more than the need of securing a job,” says Akshay Chaturvedi, founder and CEO, Leverage Edu, a higher education and career guidance platform.

Harshali Padmanabh, who is pursuing arts and business from the University of Waterloo, Canada, says the reason behind opting for liberal arts was the exposure to a wide array of subjects. “I did not know what I wanted to get out of the degree back then, but I knew I wanted to acquaint myself to newer ideas for which the degree seemed ideal,” she says. “Employment is a secondary consideration. When you want to learn life skills, charting out a unique path becomes the focus.”

Chaturvedi adds that though it’s still an urban concept, over the last three to five years such courses are being increasingly opted for by people from Tier II and Tier III cities as well, indicating the rising awareness about its significance.

Global vs local

Despite the efforts taken to put India’s liberal arts universities on the global map, they have failed to grab a spot even in the top 100 over the years. The reasons might be many, say academicians.

“Universities should focus on providing quality education and their interests should be towards the concerns of the students more than those of their investors,” says Balveer Arora, chairman, Centre for Multilevel Federalism, Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi.

“ We received applications that exceeded the size of the current batch by more than 10 times, a clear indication of the rising demand for liberal arts education.”

Dr Achyut Vaze, dean, Jyoti Dalal School of Liberal Arts

Azim Premji University’s Manoj P believes that liberal arts courses should be designed in accordance with India’s culture and challenges rather than mindlessly copying the US or an international model. “A good Indian liberal education is one that is well-designed, facilitates a better understanding of India, and affordably prepares students for a meaningful life and public good,” he says.

Elucidating what the Indian education landscape has to offer, Vaze says a local perspective will further develop the creative thinking, innovation, and problem-solving abilities of students. “India has a rich cultural heritage, thriving schools of philosophies and ideologies, and a vibrant political and social life. It provides a unique, multi-dimensional, and highly specialised foundation for an education in liberal arts, giving an edge to Indian colleges that cannot be replicated abroad,” he says.

Another aspect that Indian universities still lack in comparison to the ones abroad is the focus on admitting students from diverse backgrounds to enable the exchange of different viewpoints. “In India, such programmes must become truly inclusive. If the student body does not truly reflect India, and somehow becomes an island of privilege, it would not serve its intended purpose,” says Manoj P.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)