What Renuka Sugars Learnt From Brazil

Narendra Murkumbi has learnt some bitter lessons with his Brazilian ventures, but he might be putting them to good use

There really is no way to sugar coat this. Narendra Murkumbi is in a tight spot.

In 2010, he was the poster boy of the Indian sugar industry. He had been responsible for India’s largest investment in Brazil, a country where Shree Renuka Sugars, founded in 1998 by the mother-and-son duo, had picked up two ailing sugar mills.

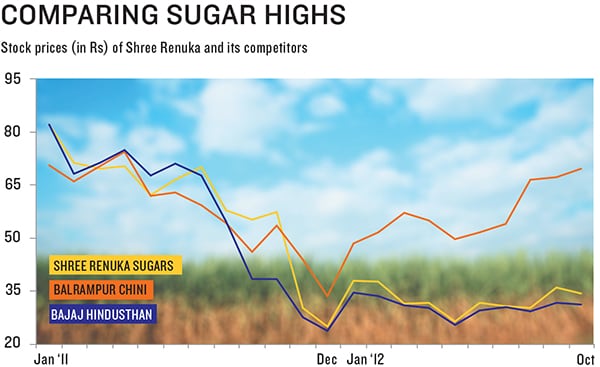

Two years later, Murkumbi’s company Shree Renuka Sugars has all its vital statistics messed up. Last quarter, Renuka do Brasil, the larger of the two mills, lost Rs 116.7 crore. This has proved a drag on the company. Its stock price is Rs 35, one-third of what it was when Murkumbi made his acquisitions. The debt on the balancesheet has doubled to Rs 9,100 crore, and interest expense is one of the biggest destroyers of shareholder value now.

Selling assets is one option. The company has been trying to sell a Renuka do Brasil asset that produces 138 MW from a co-generation power capacity (cane crushing units can also generate power). With power prices low in Brazil, Murkumbi says he’s having difficulty finding a buyer.

Joe Louis, the legendary boxer, once said: “Everyone has a plan until they’ve been hit.” So did Murkumbi. In an interview at his Worli office, in mid-town Mumbai, he admits: “I myself was not fully aware of the depth of the problem, and it is a new and humbling experience.”

To be fair, it is not as though Murkumbi was under any illusion that turning around his Brazilian investments would be easy. But think of an ambitious homegrown Indian company that, in its first decade, acquires an asset twice as large as the ones it has in India; add to that the operational challenge of conducting a business in a country with an alien language and culture, and 11 time zones behind. And the result, as Murkumbi puts it, is “information flows were a challenge”.

But the weather is turning favourable for Shree Renuka. Murkumbi has increased his personal and his team’s level of involvement in the Brazilian operations. They have learnt some tough lessons, and are now effectively putting them to use.

For now, the company is holding its head above water where debt repayments are concerned. It needs to sell sugar at more than 22 cents per pound. It’s already hedged half its production at 22.5 cents per pound. Global sugar prices have ranged between 19 and 23 cents per pound since April.

The Plan

What exactly was Murkumbi trying to do with the acquisitions?

To understand why Murkumbi ventured into Brazil, a place where no other Indian sugar company has stepped foot, one needs to look at its business operations in India.

The Indian sugar industry is highly politicised: The government decides how much companies pay for cane, how much they can sell in the open market, and how much they can export. Companies are also prohibited from growing cane.

Indian sugar mills are owned either by families who have been in the business for generations, or by state- and farmer-run cooperatives.

Into this industry Narendra Murkumbi, and his mother Vidya, entered like a gale force in 1998. They bought an old mill in Andhra Pradesh, trucked it to Belgaum, Karnataka, and raised operating finance by offering farmers a stake in the mill. Being completely new to the business, they partnered with farmers rather than have an adversarial relationship with them, something that mills across the country are known for.

By the early 2000s, their model was an acknowledged success, and the company had expanded to seven mills by taking over sick mills, partnering with farmers, and turning them around. In 2005, when the company listed to raise a modest Rs 100 crore the market lapped it up; the issue was oversubscribed 15 times—an incredible performance even in those bull market days. Since then the stock has risen four times, and the company has rewarded shareholders through bonuses and stock splits.

It was by 2006 that Murkumbi went looking for his next big challenge. The answer came from half-way across the world—Brazil, a country that moves the world sugar markets.

On paper, the plan was rock solid, and its main aim was to counter the cyclical nature of the sugar industry in India. Here’s how it works: India is the world’s largest consumer of sugar, and needs 24 million tonnes (MT) a year. But yearly production oscillates between 18 MT and 26 MT. When production falls short, the government, in an ad-hoc manner, allows imports. Similarly, when there’s a glut, it allows exports.

Add to this the fact that crushing season in India lasts for six months, from October to March. This leaves companies unable to take advantage of, say, improved global prices at other times of the year.

Now, imagine a company that has the capability to produce sugar all year long. Being in the southern hemisphere, Brazil’s crushing season is from April to December, which nicely complements India’s. Its other advantage is the lack of restrictions on exports. “Our aim was to have year-long production capacity to balance demand,” said Jonathan Kingsman, an international expert on the sugar industry and a board member at Shree Renuka Sugars, in a February 2011 interview.

With the financial crisis lowering asset values, in March 2010, Renuka acquired Vale do Ivai (to become Renuka Vale do Ivai). In July, 2010, it acquired Equipav SA Acucar Alcool (to become Renuka do Brasil). They cost Rs 6,500 crore ($1.3 billion), roughly the same as its then market cap. Both mills added 70,000 tonnes crushed per day (tcd) to Shree Renuka’s capacity, compared to the 40,000 tcd it has in India.

Unlike India, where mills buy cane from farmers at a fixed price, the Brazilian mills came with their own huge plantations. In southern India, which grows more productive cane than the north, the yield averages 65 tonnes per hectare. In Brazil, with mechanised farming, the yield is 80 tonnes per hectare. While the sugar content in Indian cane is 9.5 to 11.5 percent, in Brazilian cane it is 14 percent. Indian cane has to be planted afresh every two years, in Brazil it is six to eight years.

The Unforeseen

And then, the plan took a hit.

It can’t be denied that the events were beyond Murkumbi’s control. In 2011, Brazil suffered three months of drought, for the first time in a decade. Then, unexpectedly, in the winter months of June and July, there were two instances of frost. “In such a situation, the crop stops growing. So, instead of sugarcane that is, say, two metres tall, we were left with cane that was only one metre tall,” says Gautam Watve, chief executive of Shree Renuka’s Brazil operations.

Watve says that the company has had experience in turning around distressed assets in India. But, unlike in India, where farmers grow cane, in Brazil, the company cultivates 102,000 hectares. Clearly, agriculture was not its forte; something Murkumbi and his team are working overtime to address.

The drought not only reduced the harvested quantity of cane, it also reduced yields to 59 tonnes per hectare, from 80 tonnes per hectare.

The plantations had to be replanted. Brazilian cane has a life cycle of seven years. With each year, its sucrose content decreases, and by the seventh year the yield drops to a fourth. Replanting each hectare costs $2,500 (Rs1.25 lakh), and, given the costs, the previous plantation owners had gone easy on replanting.

This is a huge investment, and industry watchers say that if Shree Renuka had been more aggressive in replanting, it would have been in a better position. Vikash Jain of CLSA wrote in a report: “Renuka’s disappointing performance in FY12 was entirely driven by a drop in cane yields due to a lack of new planting as well as unfavourable weather.”

CLSA, however, believes the company can turn things around and has put a ‘buy’ on the stock.

Now what?

Does Murkumbi have a plan B?

Murkumbi admits it took them longer to anticipate the drought and react to operational challenges. Initially, he had operated the two Brazilian companies as independent entities, and had not changed their management. But since the beginning of this year, he makes sure he receives information every day.

Murkumbi is also spending a lot more time in Brazil—15 days every month. He’s well versed with the operations of a mill, and spends time on the shop floor, driving his team. In India, his work day stretches till 2 am, when he finishes his daily calls with his office in Sao Paulo.

He has also changed the company’s management: Paulo Adalberto Zanetti, CEO of Renuka do Vale, comes from an agriculture background and has taken over as CEO of both the companies. And Watve, Murkumbi’s head of strategy and planning, along with four members of the finance team, have relocated to Sao Paulo.

With good weather, Shree Renuka expects yields to rise to 65 tonnes per hectare and move towards 80 tonnes per hectare over the next two years. The last two months have seen 26 percent higher cane crushing, at 4.6 million tonnes.

With costs being fixed, the company would be on track to improve profitability. It is also working on cost savings: By combining procurement of fertilisers and farm equipment for its Brazil operations it was able to reduce operating costs by eight percent. Shree Renuka has also reconfigured its mills to produce either sugar or ethanol, based on prevailing prices for both commodities.

If the increasing profits of the past two quarters are any proof, then it does mean that Murkumbi and his team are slowly coming up with the answers. Foreign financial investors (FIIs), who held a large percentage of his stock, had sold their holdings. So had Indian fund managers. (FII investments and institutional holdings are down in the sector as a whole because of its cyclical downswing.) Seeing these investors getting back into the Shree Renuka story will take more time, but will also indicate a recovering company.

Murkumbi has a while to go before being back on a poster.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)