Vince McMahon's Direct-to-Fans WWE Network

Pro wrestling billionaire Vince McMahon sucker punched his traditional television partners when he launched his direct-to-the-fans WWE Network earlier this year. The unorthodox manoeuver could transform his business— or he could fall flat on his face

Subtlety has no place in professional wrestling. Either you play big—to the smallest fan in the last row of a sold-out arena, to the millions tuning in each week on television—or you go home. And no one has understood that concept, what Roland Barthes once described as wrestling’s “spectacle of excess”, better than Vince McMahon.

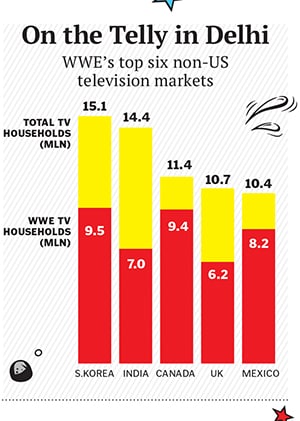

In the four decades he has ruled World Wrestling Entertainment, the 68-year-old chairman and CEO has built the company from a solid regional operation to a powerful international brand that’s valued at $2.3 billion. Today, in addition to weekly television shows, which reach 15 million viewers in the United States, WWE has programming in more than 150 countries and 30 different languages. There are WWE movies, books, videogames, as well as the requisite T-shirts, hats and action figures.

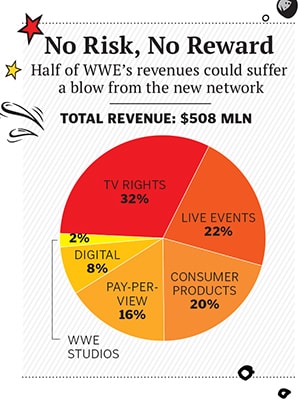

Despite the breadth of its businesses, revenues have barely budged over the last few years, hovering at around $500 million since 2008, and profits have been similarly stagnant. Excluding a one-time writedown of $11.7 million, the company made $14.5 million last year, compared with $31.4 million in 2012 and $24.8 million in 2011. Despite these flaccid fundamentals, WWE’s stock price has more than tripled in the past six months, zooming from $9.70 in September 2013 to a recent all-time high of $31.98, enough to make McMahon, who owns 52 percent of the thinly traded shares, a billionaire once again (he was briefly a paper billionaire in 2000).

The shares are flying both because WWE is seeking a new television contract, at more than twice its current rate of $160.9 million, and because of persistent speculation that McMahon, who has never articulated a clear succession plan, might sell the company outright (both Comcast and the Madison Square Garden Co. have been rumoured as suitors). Another bright spot: Emerging market revenue has been growing at a 7 percent annual rate for a decade in countries such as India, Mexico and even South Korea, to $116 million last year.

But the world—and a ten-figure fortune—is not enough for McMahon. Which is why he roostered onto the stage at Las Vegas’s Consumer Electronics Show in January to announce a bold new venture: The WWE Network. McMahon told the cheering audience that the WWE Network would not be broadcast on cable television, where Monday Night RAW has consistently been a top-rated programme each week, nor would it be another pay-per-view (PPV) play. Rather, the WWE Network will stream content 24/7 directly to viewers on the internet or what’s known in the entertainment industry as going over the top. It’s a move that directly endangers both WWE’s PPV revenues ($82.5 million) and its potential new TV deals, a huge gamble that according to some estimates could double the size of the WWE’s business in two years—or fall flat on its face, enriching sceptical investors who have sold 4 million shares of the company short. It’s risky, exciting and deeply unconventional.

Of course it is. Why would Vince McMahon do it any other way?

In his black-and-red office at WWE headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut, McMahon stares at a stark reminder of what motivates him. To the left of his desk, mounted on square panels of what looks like scarlet fur, is an enormous dinosaur skull. The fearsome open jaw was a gift from his son-in-law, Paul Levesque, better known to wrestling fans by his nom de guerre, Triple H. And the metaphor isn’t lost on McMahon.

“I look at it like it’s a really nice monster,” he says in a low, gravelly voice familiar to millions of wrestling viewers who know him as “Mr McMahon”, the megalomaniacal lord of the ring. “When you feed the monster, the monster is happy. The problem with that is, the monster grows. And as the monster grows, then the monster wants more to eat. And as long as you do that, everything’s great. And if you don’t provide the food, then bad things start to happen.”

Is the monster the audience?

“You can look at it that way, absolutely,” McMahon says with a smile.

Or it could be the competition— whether it’s mixed martial arts, the NFL or Marvel superhero movies that are vying for his younger viewers, 21 percent of whom are under 18. And in part, the beast represents his own insatiable desire to win.

Over the past two years WWE has spent $75 million preparing for the launch of the WWE Network, which went live on February 24. The initial demand was enough to crash the servers of WWE’s technology provider, Major League Baseball’s MLB Advanced Media, but success is no sure thing. Still McMahon lives for these kind of risks, especially when it comes to technology. He embraced closed-circuit television early in his career, and though boxing beat wrestling to the televised punch when it came to pay-per-view events, McMahon is considered a pioneer of PPV programming.

He has been promising fans and investors a WWE Network since 2011, and in that time the vision for it has changed dramatically. It was first conceived as WWE’s version of the MLB or NFL Network. In theory a channel devoted to wrestling makes even more sense than a professional sports league, since, unlike baseball or football, WWE doesn’t have an off-season. (It puts on more than 300 live shows, 52 weeks a year.) But McMahon claims that model was only going to generate an anaemic 20 cents per month per subscriber, roughly on par with third-tier networks like MSNBC and Bravo, $0.21 and $0.24 a month, respectively (almighty ESPN commands an astronomical $5.54 a month). So he walked away.

The next plan for the network followed a pay-channel model (like HBO), but again McMahon didn’t like deals he had in place. So in true wrestling fashion, WWE kicked out of them in 2012 and began exploring the over-the-top strategy. The phenomenal success of Netflix, which now has more than 44 million subscribers, inspired WWE to seek a model that went directly to its biggest asset: Its passionate fan base.

If WWE Network takes off and doesn’t destroy the company’s pay- per-view and cable TV businesses in the process, it will dramatically change the corporation’s economics. It could also change the way similar companies do business. UFC and the boxing PPV divisions of HBO and Showtime are surely waiting to see if McMahon has bet right. And yet, for such a risky venture, the math to success is relatively simple.

For $9.99 per month (and a six-month commitment) subscribers will have access to more than 130,000 hours of WWE programming, matches that date back to the 1950s. There are also original programming and a “second screen” experience on the WWE app that allows viewers to interact with one another and watch live content during commercials.

But the real draw of the subscription is that WWE Network will broadcast all 12 of its PPV events. When you consider that the average WWE PPV costs about $55, a customer who was previously purchasing two PPVs will feel like he’s getting the better of Vince McMahon.

Allowing for the cannibalisation of its existing PPV customers (which WWE estimates could be as much as $60 million a year), the company needs 1 million subscribers to break even. At 2 million subscribers WWE projects adding $50 million to its EBITDA. At 3 million that number jumps to a robust $150 million.

Naturally, some of WWE’s television partners felt sucker punched by the over-the-top strategy. In advance of the launch, DISH Network announced it was dropping all WWE’s PPVs—including WrestleMania XXX on April 6. And DirecTV issued a less-than-thrilled statement about the new venture: “Clearly we need to quickly re-evaluate the economics and viability of their business with us, as it now appears the WWE feels they do not need their PPV distributors.” McMahon, for his part, thinks that it would be “foolish” for distributors not to carry his events, calling it “found money” for them; Vince McMahon has always made money for his partners. And, of course, himself.

Not that McMahon is keeping score. “I don’t consider myself a rich person,” he says in a rare moment of modesty. “I know that I am, but it’s not like I belong to any country clubs.”

He and his wife, Linda, live in nearby Greenwich, Connecticut, but he doesn’t exactly treat himself to expensive toys. Years ago he owned a cigarette boat called Sexy Bitch, but McMahon’s indulgences are limited these days. “I have a car that goes very fast and a motorcycle that goes extraordinarily fast,” he says of his Bentley and a Boss Hoss 502. “I love speed.” Beyond that, he adds, “I don’t really have anything in common with anyone in Greenwich except zeros. Normally I do not like rich people.”

A third-generation wrestling promoter, McMahon didn’t meet his biological father, Vincent James McMahon, until he was 12. He was raised in a trailer park in rural North Carolina by his mother and several physically abusive stepfathers. A thuggish teen who was always getting into fights, McMahon was shipped off to Fishburne Military School in Virginia, where he was a star wrestler.

During those high school years McMahon began spending summers with Vince Sr in New York and other cities in the Northeast. To a kid who grew up without indoor plumbing, the life of a professional wrestling promoter seemed glamorous. “When people would say, ‘Do you think can you follow in your old man’s footsteps?’ I would immediately say, ‘No, and I don’t want to, and I can’t fill my dad’s shoes. I have to do things my own way.’ ”

After Fishburne McMahon enrolled at East Carolina University and graduated with a degree in marketing. But he had never lost his passion for the squared circle. Vince Sr tried to push him away from the family business, but in the early 1970s he eventually agreed to let his son promote matches at a small arena in Bangor, Maine. There, McMahon learned what it took to be a small-time promoter, but he felt that wrestling could be so much bigger. And he believed he saw its future: Television.

Professional wrestling had been broadcast on national TV since the late 1940s, but by the 1960s the dozens of small-time wrestling organisations in the US, and their respective TV shows, were local. For the most part these regional companies played nicely with one another. They didn’t invade other territories or steal talent.

Vince McMahon saw things differently. If the business was going to be called “World Wide”, he reasoned, it ought to at least be national. In 1982 McMahon took his first big risk: He purchased the company from his father and his partners. “It was a balloon payment situation,” he says, “so if I didn’t make the last payment they took the business back and kept the cash.”

Once the final payment was made McMahon set off a battle royal in the industry. Territories no longer existed as far as he was concerned, and anyone’s talent was fair game. He also eventually admitted that matches were scripted, calling his product “sports entertainment”. To old-school wrestling promoters and talent, it was tantamount to a magician revealing how he saws the lady in half.

From there McMahon began an all-out television assault—largely on the suntanned shoulders of his biggest star, Hulk Hogan—to expand his brand, now called the World Wrestling Federation. He used broadcast TV and pay-per-view, and moved into cable. Within a few years his pop-culture-savvy programming was everywhere—Hulkamania and the WWF were running wild.

Over the ensuing three decades McMahon has been knocked around, even counted out, in the business. In the summer of 1994 the federal government put him on trial for illegally distributing steroids to his performers, but McMahon was eventually acquitted.

A few months later, the “Monday night war” began. Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling started using McMahon’s own strategies against him. WCW signed former WWF stars (including Hulk Hogan) and aired a competing programme, Monday Nitro, opposite RAW. For nearly two years Turner’s programme throttled McMahon’s. “It came down to attrition,” McMahon says. “Who was going to burn out before the other guy did?” In the end it was Turner. In 2001 he sold the name rights of WCW to WWF for $2.5 million, plus the entire video library of matches.

But there were huge missteps, including a WWE-themed restaurant in Times Square that cost nearly $25 million and closed after three years, and the XFL, McMahon’s disastrous attempt to bring WWE attitude and storytelling to a professional football league.

“I like learning from my mistakes and bringing the values I’ve learned forward,” McMahon says of his failures. “But I’m not good at patting myself on the back. I’m not good at looking back.”

Moving ever forward, McMahon wasn’t taking any chances to launch the WWE Network. The week before it went live, he re-signed 60-year-old Hulk Hogan. Hogan appeared on RAW on February 24 to announce the new venture, but by then the WWE faithful didn’t need a sermon from an aging god.

While the WWE has yet to release how many subscribers it has, two wrestling observers estimated that at least 250,000 signed up for the service on the first day, which would put the company well on its way to the million it needs to break even. One analyst recently predicted the WWE could even exceed its own goals and acquire 6 million to 8 million subscribers.

Not everyone is sanguine about those prospects, however. Intrepid Capital Management was WWE’s largest outside shareholder until January 2014, when it sold its 10 percent stake in the public float at a 100 percent profit. Intrepid portfolio manager Jayme Wiggins believes the WWE Network will be a tougher sell.

The network “is a slam dunk for a die-hard fan”, which Wiggins estimates to be a core of 700,000, “but I don’t think it’s going to be easy for them to get another 500,000.”

Another big question hanging over WWE is succession. As he nears 70, McMahon certainly shows no signs of slowing down. But even he acknowledges that it can no longer be his sole vision.

Assuming McMahon doesn’t sell, there are logical heirs to his ringdom, but he is understandably coy about it. McMahon’s 37-year-old daughter, Stephanie, is the current chief brand officer, and her husband, Paul Levesque, is the executive in charge of talent, live events and creative, but there is no guarantee that the company will be run by another McMahon in the future. “I would like to see a degree of that,” he admits. “I just think as times go on, things will evaporate. Eventually Uncle Sam sees the benefit. You can’t do anything without Uncle Sam taking a huge bite of it.”

And what about the monster inside Vince McMahon? Will it ever be satisfied by his success? “I have a voracious appetite, for life and everything in it,” he says. “To a certain extent I will die a very frustrated man because I didn’t do this or accomplish that.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)