The World Bank is Confused

With its $57 billion aid portfolio, muddled objectives and failure to contain corruption, a decade of reform efforts have done little to fix the World Bank

It’s presidential inauguration time in Washington. Not for the person who will helm the federal government—that comes in six months—but instead for Dr Jim Yong Kim, the man taking the reins of an organisation even more lumbering, and far less accountable: The World Bank.

With 188 member countries and an army of 9,000 employees and consultants, Kim will lead one of the world’s most powerful institutions—charged with saving the world’s poor—but also one of its most dysfunctional. It is an endlessly expanding virtual nation-state with supranational powers, a 2011 aid port- folio of $57 billion and little oversight by the governments that fund it. And—according to dozens of interviews over the past few weeks, atop hundreds more over the past five years, plus a review of thousands of pages of internal documents—problems have gotten worse, not better, at the World Bank despite more than a decade of reform attempts.

Kim, the Dartmouth College president tapped by President Obama to lead the bank, stands little chance of fixing things, say insiders, unless he is prepared to completely revamp the current system. “The inmates are running the asylum,” says a former director.

Part of the problem is philosophical: No one, starting with outgoing president Robert Zoellick, has laid out an articulated vision for what the World Bank’s role is in the 21st century. For example, economic superpower China remains one of the bank’s largest and most valued clients, even as it doles out development money to other countries and bullies the bank from aggressively investigating corruption.

Part of the problem is structural: Internal reports, reviewed by Forbes, show, for example, that even after Zoellick implemented a budget freeze some officials operated an off-budget system that defies cost control, while others used revolving doors to game the system to make fortunes for themselves or enhance their positions within the bank. Why not track all the cash? Good luck: Bank sources cite up to $2 billion that may have gone unaccounted for recently amid computer glitches.

Sadly, the last part is cultural: The bank, those inside and outside it say, is so obsessed with reputational risk that it reflexively covers up anything that could appear negative, rather than address it.

Whistle-blower witch hunts undermine the one sure way to root out problems at a Washington headquarters dominated by fearful yes-men and yes-women, who—wary of a quick expulsion back to their own countries— rarely offer their true opinions.

Zoellick declined to speak with Forbes for this piece, though that’s not surprising. I’ve covered the bank for the past five years and have been ritually denied access to anyone in a mid-to-top-level post. The blockade ended just before Forbes went to press, when the bank conducted a carefully monitored conference call with two staffers who run the global “Open Data” initiative. The bank’s media relations spokesman was permitted to be quoted by name. That this is considered openness epitomises the problems that Kim now inherits.

Like most out-of-control bureaucracies, the World Bank started with lofty and idealistic goals. Facing a planet in ruins near the end of World War II, it was created along with the International Monetary Fund at a conference of leading Western economists trying to find ways to address the economic instabilities that they believed led to war—and to guarantee it would never happen again.

Having successfully helped rebuild Europe and Japan, the World Bank eventually expanded into a truly global agency, notably in the 1970s under the leadership of Robert McNamara, who took on the goal of a poverty-free planet in his search for redemption after his role in the Vietnam War. Donor nations fund the bank with billions of dollars annually, which it then doles out to fight poverty worldwide.

In terms of its governance, the World Bank has always operated under a gentleman’s agreement that allows the US—its largest shareholder with 16 percent of the vote—to pick its president, while the other 187 member-governments flow into a 25-member board. The process for its funding, grants and loans is absurdly complicated, but in essence it combines capital from its donor countries, plus self-generated income through the sale of bonds.

While often confused with the IMF, which provides financial stability to govern- ments, the World Bank’s role is at least supposed to be only development projects—like building dams, roads, schools, even fish farms—although it has muddied those boundaries over the last 20 years. Unlike the IMF, the bank deals with both the public and private sectors, and as the number of projects and amounts of money have escalated, so has the mischief, corruption and cover-ups, since no agency has the power to audit them.

In 2005 George W Bush tapped Paul Wolfowitz as president to clean the place up. To his credit, Wolfowitz made rooting out corruption his primary mission. But the former Pentagon official also came in like an occupying power. According to internal documents obtained by Forbes, the board and Wolfowitz engaged in a game of trench war- fare so vicious that the minutes of some board meetings had to be sanitised to keep the world from knowing what was really going on.

Perhaps Wolfowitz’s heavy-handed style would have eventually paid dividends. He did, after all, declare war on the bureaucracy. But he also fell prey to the insular culture, giving his girlfriend at the bank special considerations that undercut his credibility and led to his resignation.

So in came Zoellick. He had a stellar resume, serving as the US trade representative, an assistant Treasury secretary and deputy secretary of state. Joining the bank in 2007, he immediately calmed the waters. Facing a global food crisis, followed by a financial crisis, he shovelled loans out the door at record levels to help keep the world’s poorest from being buried alive. He then turned around and sought—and last year received—healthy financial increases from the bank’s member countries.

When arriving at the bank, he was flabbergasted at the glass ceiling for women—despite 20 years of studies and internal promises to change it. Within five years he could boast that half of his top managers were female. Zoellick was also shocked to learn that the bank sold its old data and surveys in its 8,000 “datasets” going back 50 years. He ordered it to be given out for free and made available to all—except for the sensitive stuff—under what he calls the Open Data programme.

These moves, however, all fell at the margins. The bank’s core problems grew unabated. Zoellick appeared to continue Wolfowitz’s corruption battle, boosting the budget and the number of investigators in the bank’s corruption-fighting arm—which led to the bagging and debarring of a record number of companies for corruption and bribery, including Germany’s Siemens and Britain’s Macmillan Publishers.

But numerous managers and vice presidents that I spoke with inside the bank say that corruption continues unabated. Five years ago a commission led by Paul Volcker drilled into the bank and called it a massive problem. He recommended restructuring the bank’s corruption-fighting unit, including moving the leadership into a more powerful notch in the bureaucracy.

Zoellick adopted everything in the Volcker plan, but there are big questions today whether it’s having a deep impact.

“Certainly the World Bank in its official attitude has changed,” Volcker tells Forbes. “Now I can’t tell you how much that’s penetrated into the field staff … or the people who make the loans.”

Last year a little-known internal bank review was done on the effectiveness of the bank’s corruption- fighting efforts. At first, according to the report’s lead author, Navin Girishankar, Zoellick’s team asked the evaluators—based inside a semi-independent bank unit—not to review the Volcker restructuring until they had more time themselves to see how it was working. The investigators agreed, focussing instead on the end results that ultimately matter, anyway—the “quality of the bank’s operations,” particularly in countries that suffer heavily from corruption and poor governance.

The bank’s corruption fighters are too focussed on specific development projects and not enough on the budgets of poor countries, where bank funds—more than $50 billion since 2008—are commingled with a country’s income and may not be used for its intended purpose. These funds go down a rabbit hole and are almost impossible to track.

It was a bold report that shook the bank, and Zoellick’s team worked hard to discredit it.

“In the beginning they wanted to push us toward examining countries where they felt there would be successes,” says Girishankar, considered one of the best analysts inside the agency. “Then the sampling was questioned, as were the findings that the bank is not consistent in fighting corruption and improving governments across countries.”

A similar report that the bank buried, attacked and then ignored was done by another respected internal investigator, Anis Dani. This report found a “dramatic dip” in the quality—meaning effectiveness, impact and results—of bank projects over the past five years, says Dani. He also found a seemingly pre-meditated effort to remove the only whistle-blower function within the bank that dealt with all its projects, called the “Quality Assurance Group”. Zoellick’s team dissolved it in 2010, and while the bank maintains that it is working on replacing it with something else, Dani calls that claim “hogwash”.

The study, presented to the board in February of this year, was objected to by the bank’s senior managers, who pre-emptively produced their own Power-Point presentation that found a lot of the same problems that Dani did. (That report has never been released.)

None of these apparent attempts to blunt unwelcome news comes as a surprise to Carman L Lapointe, who has worked as the UN’s chief internal watchdog since 2010. Before that Lapointe was the auditor general of the World Bank, where her team issued 60 internal reports per year on what was really going on inside the agency.

“Carman’s reports were—how can I put it—a bit candid,” laughs a bank vice president who supported her. But it led to Lapointe being gently walked out the bank’s door in late 2009.

“We were pretty blunt with what had to be said, and that’s not what those at the top of the bank want to read,” Lapointe tells Forbes. “The bank’s management didn’t want to hear the tough messages. They are very reluctant to be held to account.” The bank wouldn’t comment on that, although Lapointe says she confronted Zoellick before leaving, and he told her he’d been blindsided by his own top managers.

At the most fundamental level the World Bank has a mandate problem. Economist Adam Lerrick, a longtime critic of the organisation, argues that it lost its bearings lending to middle-income countries “that don’t need the money,” like the BRIC countries—Brazil, Russia, India and China—rather than sticking with development projects in the world’s poorest and most fragile states.

The bank argues that it makes money from lending to the BRICs, which allows it to lend still more money to the poorest nations. In a 2006 study, however, Lerrick drilled down into the bank’s books and found real annual losses of $100 million to $500 million per year on its loans—although accounting manoeuvres painted a rosier picture of the financials. It’s hard to believe the situation has improved in the wake of the financial crisis.

“The World Bank should be in the development business, not the lending business,” says Lerrick. “Its scarce donor-backed funds should be channelled to countries that do not have access to private-sector capital.” Volcker has previously likened the bank’s we-must-lend attitude, ominously, to Fannie Mae.

Nowhere is the problem clearer than with China, the world’s second- largest economy—and the World Bank’s second largest customer behind Mexico, having borrowed more than $30 billion over the past few decades. When China in 2007 threatened to stop borrowing from the bank unless the agency toned down its new corruption-fighting plan—according to a secret internal bank memo, obtained by Forbes—the bank’s top managers went into a panic and quietly caved.

“The bank is desperate to keep its best clients,” explains Lerrick.

A decision was made inside the bank—announced on its website but wrapped in diplomatic jargon—that they would benchmark each country individually on corruption, rather than against one global standard. The practical result was an easing of the rules for the biggest violators, such as China.

Zoellick, who prides himself on his relations with China’s leaders, did nothing to alter it. Indeed, in the report issued last year by Girishankar, he confirmed that this was happening. “There are several countries, including those with very big geopolitical influence and a strong voice on the bank board, where the bank had to find a way to deal with it,” he says.

It gets worse: Hardly a month now passes without an announcement that the World Bank is lending China a tonne of low-interest money—say $300 million to clean up a polluted lake—only to watch China turn around a few days later and announce a similar-sized zero-interest loan, or grant, to a poor sub-Saharan nation, winning extra global clout.

Meanwhile, inside the bank’s Washington headquarters, China is increasingly assertive on the board level, while bank managers kowtow to China. Case in point: In the China office at the bank in Washington, one staffer’s job, according to a recently retired senior bank official, is to closely examine every World Bank document the bank creates that mentions Taiwan to make sure that it uses language China approves of. If it doesn’t, the language is altered.

When Zoellick took office five years ago, he instituted, he says, a flat budget on the agency—which, to outside eyes, remains at roughly $2 billion annually for administrative overhead. He did it because he felt it would instill discipline on the global staff and honestly felt they could do more with less. Unfortunately, Forbes has learned, the staff simply did an end-run around the president.

“No one believed we had a flat budget except him,” laughs a senior vice president. “We’re spending trust funds like there’s no tomorrow. So where is the flat budget? Everyone just got money from bank owners in a different capacity.”

“Trust funds” are the World Bank’s dirty little secret, their version of Congressional earmarks. There are hundreds of them, funded by dozens of countries and dedicated to virtually every poverty-type project you can think of. And they have been growing so phenomenally that they now provide $600 million annually, or 30 percent of the bank’s total administrative budget.

Many donor countries do this because they don’t want their money sitting in a general bank fund that the bank can use for anything it wants. But since they have various arms of the bank administering these funds, there’s even less oversight than there would have been otherwise. And while those trust funds are generally not supposed to go toward administrative overhead, they often do anyway, say bank insiders, which many countries are unaware of. Forbes has turned up examples—such as with Italy—in which arms of the bank have been charging headquarters and individual countries for the same salaries and expenses, helping to enrich bureaucratic fiefdoms. Forbes has also discovered a whole layer of bank officials who have learned how to game the system or expand their influence through its constantly revolving doors.

As just one example, “Lead Education Specialist” Luis Crouch helps manage the billion-dollar Global Partnership for Education, run out of the bank’s headquarters. Crouch is a revolving door within a revolving door—over the past 10 years he has shuttled back and forth between the bank and Research Triangle Institute (RTI), a nonprofit that sells education tests to the bank and USAID, according to a USAID consultant familiar with the deals who says Crouch consistently favours RTI. Asked about his apparent conflicts of interest, Crouch declines to comment, while bank spokesmen also decline.

With such off-book shenanigans going on, perhaps it ’s not shocking that last December more than $2 billion suddenly started appearing, disappearing and reappearing across the online budget accounts (and computer screens) of bank units around the world, according to staffers responsible for those budgets. In some accounts they showed huge deficits where none had been, while in others there were sudden surpluses. This was popping up in unrelated units across the bank’s computer networks—and driving everyone crazy trying to figure out what was happening. One insider likened it to the game whack-a-mole—only with hundreds of millions of dollars shooting up in different spots and vanishing from others.

One possibility could be that it was massive hacking—an incessant problem at the bank. Another explanation is that it was simply “Computers Gone Wild”—perhaps the IT network on its own playing a game. Others suspect the explanation may be more nefarious. One thing for sure: It eroded confidence in the World Bank’s controls. Zoellick’s hands-off management style didn’t help, either. He delegated most day-to-day functions to a deputy, Caroline Anstey, as well as delegating to her and two others the chairing of most board meetings—which is normally the function of bank presidents.

The board meets twice a week, and yet Zoellick shows up maybe once a month. At the beginning they grovelled for his attention, until he started going behind their backs to get information directly from their bosses (the finance ministers of their countries).

Indeed, Zoellick fashioned himself more in the role of a statesman than a bank CEO. He is rumoured to be eyeing a senior job in a Romney Administration. Given this, bank insiders say that Zoellick’s goal—with bigger career perches in mind—has been to simply manage the agency in a way that there is no noise or blame that could be affixed to him.

That meant not taking big risks. In late 2008 Zoellick tapped former Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo to chair an independent commission to study the issue of giving smaller and poorer countries a bigger seat at the World Bank governance table. That report was sent to Zoellick when it was completed last year, who promptly gave it to the board—but not before adding a cover letter saying it doesn’t necessarily represent his views.

“Why did he have to do that?” Zedillo asks Forbes. “It was very obvious it was an independent report. He didn’t have to say that. He was not the author of the report at all. I think he’s afraid some country members will jump to his neck, blaming him for the report. They can blame me if they don’t like it.”

One of the Zedillo commission’s biggest conclusions is that “the board should be a real board and not an executive board,” says Zedillo. “The board should handle strategic matters and oversee seriously the activities of the bank. Right now it has a conflict of interest.

“You cannot be the overseer and also the approvers of the operations,” he adds with a laugh. “But that’s been a practice since the bank was established. … Do they really think the World Bank will be relevant in 10 to 15 to 20 years if you keep it the way it is now? The answer is no.”

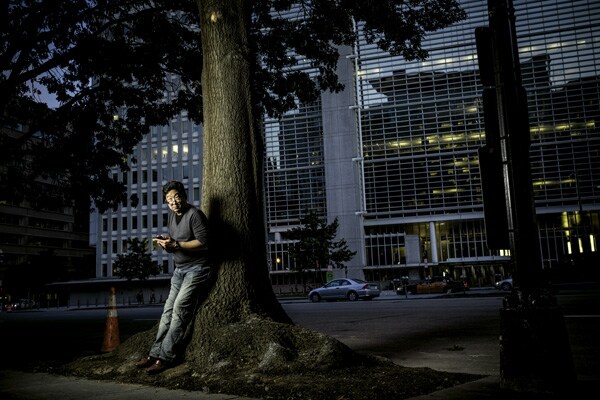

Image: Stephen Voss for Forbes

WHISTLE STOP

The World Bank is a place where whistle-blowers are shunned, persecuted and booted—not always in that order.

Consider John Kim, a top staffer in the bank’s IT department, who in 2007 leaked damaging documents to me after he determined that there were no internal institutional avenues to honestly deal with wrongdoing. “Sometimes you have to betray your country in order to save it,” Kim says.

In return bank investigators probed his phone records and emails, and allegedly hacked into his personal AOL account. After determining he was behind the leaks the bank put him on administrative leave for two years before firing him on Christmas Eve 2010. With nowhere to turn, Kim was guided into the offices of the Washington, DC-based Government Accountability Project—the only game in town for public-sector leakers. “Whistle-blowers are the regulators of last resort,” says Beatrice Edwards, the executive director of the group. Edwards helped Kim file an internal case for wrongful termination (World Bank staffers have no recourse to US courts) and in a landmark ruling a five-judge tribunal eventually ordered the bank to reinstate him last May. Despite the decision, the bank retired him in September after 29 years of service.

The US is beginning to notice. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee insisted on inserting a whistle-blowing clause in 2011 after World Bank President Robert Zoellick approached them for an increase in the bank’s capital. But because of the supranational structure of the bank, the Senate’s demands are ultimately toothless.

“We can’t legislate the bank,” explains a Senate staffer. “All we can do is say, ‘We’ll give you this [money] if you do that [whistle-blower protection].’ But they say, ‘You can’t make us do that because we can’t answer to 188 different countries.’”

—RB

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)