The Kings of Private Equity

Private equity is the most politicised, scrutinised, vilified industry in America. Yet David Rubenstein and the Carlyle Group, once poster children for creepy Beltway connections, have managed to both avoid the criticism— and rake in billions

Here’s a typical David Rubenstein Wednesday. Waking in Philadelphia, he joins Chinese businessmen to attend a Wharton programme set up jointly by the Chinese government and the Carlyle Group, the massive Washington, DC-based private equity firm he helps run. Then he hops on a Carlyle investment committee call to discuss imminent deals. By midday, he’s back in the capital, lunching at the White House with an old friend, National Security Advisor Thomas Donilon, before returning to the office to prepare with some of his dealmakers for Carlyle’s upcoming investors conference.

In the evening, he’ll give a speech to the mutual fund industry’s lobbying group. And the rest of the week continues apace, from talking with an investment group in Michigan to interviewing prospective hires and dining with Jamie Dimon in New York. Come Saturday, Rubenstein has a down day: Teaching a Princeton class and hosting a dinner featuring an expert on how pandas reproduce (he pledged $4.5 million to the National Zoo in 2011 to promote panda procreation).

At 63, Rubenstein uses his plush Gulfstream G550 250 days a year. He says he enjoys the busy lifestyle, but behind almost every Rubenstein dinner, speech and self-effacing comment is something more: The prospect of a sale. This is not the kind of thing they teach at Harvard Business School, though Rubenstein, the 250th-richest person in the US, with an estimated net worth of $1.9 billion, believes it ought to be. “I am on some 30 nonprofit boards, which I love and to which I give a lot of money, but the networking is helpful to my firm,” Rubenstein explains. “I can help build the firm because of the contacts I make.”

With $156 billion under management, Carlyle has more private equity funds, investors and assets than any other firm, including Blackstone Group, which manages $190 billion but has large real estate and fund of funds operations to complement its private equity group. Carlyle owns 209 companies, more than any other buyout shop, ranging from Hertz to Mrs Fields cookies, and it has distributed $52 billion to its private equity investors since inception. Rubenstein and his two long-time partners, William Conway Jr and Daniel D’Aniello, all rank near the top of Forbes’ inaugural statistical ranking of the top private equity dealmakers, which places a big emphasis on profitable investment exits and fundraising.

“David is the most prolific fund- raiser maybe the planet has ever seen in any field—and Bill Conway is one of the greatest investors I have ever met,” says Jimmy Lee, the JPMorgan Chase banker who has played a key role in the proliferation of the leveraged-buyout industry. “Those are the two businesses of private equity: Raising money, because if you don’t raise money there is no business, and investing the money wisely, because if you don’t invest wisely, you can’t raise the money.”

And while the three Carlyle co- founders have been at the buyout game together for 25 years, they’re not slowing down. Carlyle has been buying companies at a frenzied pace, striking $16 billion in deals in 2012, more than any other private equity firm. With a string of recent big announcements, like a $3.3 billion deal for Getty Images and a $4.9 billion purchase of DuPont’s car paint business, Carlyle is leading the private equity business in the biggest barrage of dealmaking seen since before the 2008 economic meltdown. More fundamentally, in May, their firm conducted an IPO, part of Rubenstein’s plan to extend Carlyle into products like funds of funds and credit investment management—and create a more diversified financial institution that can survive without him, Conway and D’Aniello.

And as all this has happened, this firm, which not too long ago was demonised by filmmaker Michael Moore and has been the subject of elaborate conspiracy theories, largely escaped the controversies currently dogging the industry as a whole. Firms like KKR and TPG have reportedly been subpoenaed by New York’s attorney general as part of an investigation into the con- version of private equity management fees into more lightly taxed carried interest—a practice Carlyle has never employed. Private equity titans like Steve Schwarzman and Leon Black still carry the stigmas of their million-dollar birthday parties, while the former became an even bigger lightning rod after he compared efforts to raise taxes on private equity firms with Hitler’s invasion of Poland. And, of course, President Obama has bashed the industry in the course of vilifying Bain Capital, the firm started by his opponent, Mitt Romney.

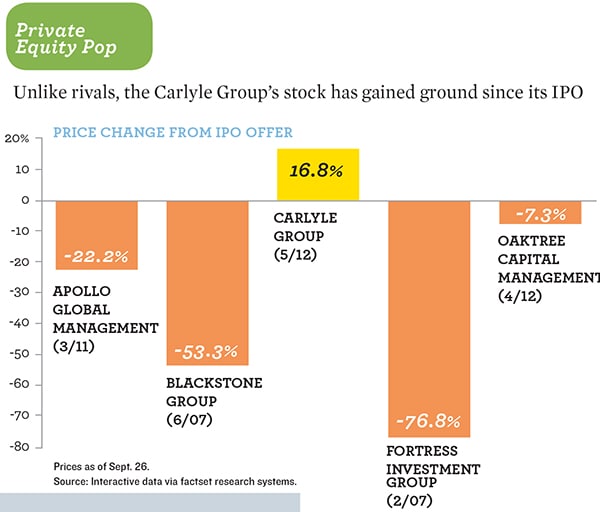

By contrast, Rubenstein is pretty sure Obama likes him. It was Carlyle that worked with the White House to buy a Philadelphia oil refinery in September, saving 850 union jobs and averting a fuel-price increase in the Northeast. When an earthquake cracked the Washington Monument last year, Rubenstein donated $7.5 million to help fix it. Rubenstein was the first private equity executive to sign the Giving Pledge, promising to contribute half his wealth to philanthropy. Unlike other publicly traded firms like Blackstone and Apollo Global Management, Carlyle’s stock sells above its IPO price.

Because of all this, Rubenstein is both the industry’s friendliest face—and its best defender. He thinks Romney’s big mistake was trying to argue that his private equity work created jobs, instead of just focusing on what private equity was made to do: Manufacture investment returns. “People generally don’t love investors and people who have made great wealth,” says Rubenstein. “In the past, no investor ever asked me how many jobs I created; they never cared. But they did say, ‘Give me my rate of return.’ ” Rubenstein adds: “We have made a lot of money for our investors, and most of them, not all, are big public pension funds who seem to like the returns.”

Washington is an ironic town, and there may be nothing there more ironic right now than this: As the White House pummels the private equity industry, the most successful private equity firm’s roots come from the White House. Rubenstein, son of a Baltimore postal clerk, got his law degree at the University of Chicago and served as a policy advisor in the Carter White House. After Reagan’s landslide he had no interest in fading into some advisory role career. He wanted to be the man making big decisions. His inspiration: William Simon, who served as Treasury Secretary under Nixon and Ford before investing some $330,000 in the 1982 leveraged buyout of a greeting card company, Gibson Greetings, that yielded Simon a $66 million payday.

But Rubenstein was not a finance guy. For six years, he puttered in private practice in Washington before finding two financial minds, Conway and D’Aniello. In 1987, they raised $5 million with the help of Ed Mathias, a friend of Rubenstein’s who worked at T. Rowe Price. There were deals involving Alaskan tax writeoffs and some early investments that tanked, and the firm barely survived that year’s stock market crash. But while D’Aniello, an ex-Marriott finance executive, kept their new investment firm running smoothly handling administrative tasks, Conway, a former MCI Communications chief financial officer, mastered the art of buying companies, incentivising the managers with ownership and working to change them over a period of time before putting them up for sale. Carlyle’s private equity funds have averaged 18 percent annual net internal rates of returns since inception, consistently ranking in the top quartile of their peer groups. Like virtually all private equity shops, Carlyle collected its “1.5-and-20” fees—1.5 percent of the assets plus 20 percent of profits—making the three cofounders billionaires.

Carlyle also amassed a slew of for- mer government heavyweights—and an accompanying cloak-and-dagger reputation. Given their location, the partners initially focussed on defence deals, a strategy aided by Rubenstein’s hiring of former Secretary of Defense Frank Carlucci and by an increase in military spending after the post-Cold War lull, spurred by the first Gulf War. “The early success in defence helped us understand that we had a core skill of dealing with businesses that are heavily impacted by government policy,” says D’Aniello.

Rubenstein made sure Conway had plenty of cash to put to work by pioneering the idea of raising multiple funds simultaneously. And to impress all those potential investors, he supplemented Carlucci with a former Secretary of the Treasury and State (James Baker), a former British prime minister (John Major) and then a former US President (George HW Bush). “If I invited you to a dinner 15 years ago to hear David Rubenstein speak, you would throw that invitation away,” says Rubenstein. “If I invited you to a dinner with Jim Baker or John Major, you would go.”

All of this took place from the ultimate Washington power location, an office on Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and the US Capitol. If you have seen the movie Broadcast News, you’ve seen Carlyle’s relatively modest second-floor offices, which Rubenstein leased after the movie was shot there. He refuses to leave the space, calling it lucky, even though to visit some of his partners he has to walk through a hallway that can be seen from the building’s lobby.

After 9/11, however, these government ties began to backfire. Private equity firms were rolling in money, courtesy of Alan Greenspan’s low interest rates and alpha-hungry pension funds desperate for fat returns that could help them meet their mounting obligations. But Carlyle’s cash pile seemed tainted. Its ties to the Bush family at the time of the second President Bush’s military ramp-up didn’t look good. Carlyle investments from prominent Saudis—notably the Bin Laden family—looked still worse. Cynthia McKinney, then a member of Congress, called out Carlyle and said, “Persons close to this administration are poised to make huge profits off America’s new war.” The Economist magazine wrote that “the secretive Carlyle Group gives capitalism a bad name”.

Carlyle ended up asking the Bin Laden family to take back their money, and eventually the former government officials retired. “I made a mistake of having too many of them, and when George W Bush got elected I should have recognised that we would be seen as a proxy for that administration if his father was still here,” says Rubenstein. “Ultimately, they retired, we depoliticised the image, and now we are the least political firm even though we are in Washington.”

The credit crisis would prove to be an even bigger challenge. Conway had an inkling a crash was coming. “I know that this liquidity environment cannot go on forever,” Conway wrote in a January 2007 staff memo, which admitted that cheap debt as opposed to Carlyle’s investment genius had been responsible for much of the firm’s fabulous profits in the period. “I know that the longer it lasts, the worse it will be when it ends.” After telling his dealmakers to be “careful”, Conway instructed Carlyle-owned companies to secure and draw on their credit lines early in 2007, helping Carlyle’s private equity portfolio weather the financial crisis relatively unscathed. There were some losses, like those stemming from the bankruptcy filing of portfolio company Hawaiian Telcom. The Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund that bought 7.5 percent of the Carlyle partnership for $1.35 billion saw the value of its investment plummet. But the biggest crash for the firm occurred outside the private equity arena in Carlyle Capital, a highly leveraged credit fund listed in Amsterdam that purchased residential mortgage-backed securities and cratered, causing $900 million in investor losses. The core business emerged in a strong position just in time for the most recent run-up.

Rubenstein currently is doing what he does best: Raising yet another buyout fund—a $10 billion monster. He’ll surely get it done, though all these money-raising events also create an inevitable problem. The more assets a firm has under management, the harder it gets to find enough attractive targets to pop an above-market return.

Conway remains bullish: He thinks the US economy endured its worst stretch of the year between April and June, and will continue to be reason- ably good. Encouraged by relatively cheap financing, Conway has secured interest rates of about 6 percent for his most recent deals—seemingly high in an environment where good returns are rare, but Conway finds costs like that attractive. He patiently waited for there to be good deals coming out of the financial crisis, and now he has pounced. “When you want to buy low, people generally don’t want to sell,” says Conway. “They hang on by their fingernails, waiting for things to get better, and frankly, it did, so I do think now is a good time to invest.”

In the last year, Conway has found opportunities snapping up assets from reeling European banks in need of capital, signing deals to buy bond manager TCW from Société Générale and Spain’s Telecable from Liberbank. He bet on industrial companies, inking a $3.5 billion deal to buy Hamilton Sundstrand with BC Partners from United Technologies, which needed cash to buy an aerospace supplier. Carlyle outmanoeuvred others for this prize by making a simpler single bid for Hamilton’s three pump-and-compressor units, while most other serious buyers were interested in acquiring only a single business line separately. Conway plans to buy more and has told investors in the $13.7 billion fund Carlyle raised in the boom years that he won’t have any trouble putting the $2 billion still committed to the fund to work prior to a mid-2013 deadline. Carlyle has also found ways to exit out of investments like Booz Allen Hamilton, which in August paid Carlyle a $620 million dividend, meaning Carlyle’s $910 million 2008 investment in the consulting firm is now worth $2 billion. Carlyle, across all its asset classes, distributed $18.8 billion to its investors last year, more than ever before. In the first six months of this year, it distributed $6.7 billion.

With 1,300 employees and offices from Barcelona to Beijing, Carlyle has been using a global approach to try to offset the challenge of managing larger funds. At the centre of that approach is a concept developed by D’Aniello called One Carlyle, which calls for all Carlyle employees to collaborate across industries and geographies.

Conway quickly rattles off examples, like when he took his US-based health care investors down to Australia to analyse a hospital deal. Carlyle’s deal for Moncler, maker of the $1,000 ski jacket, is another example. It only had stores close to Milan when Carlyle invested some $200 million in 2008. Carlyle helped transform the company into a global brand by getting its staff in Asia to work with Moncler to open dozens of global stores, and by the time Carlyle sold a big chunk of its Moncler stake last year for $500 million or so, half of Moncler’s sales were in Asia and its biggest store was in China. Carlyle still retains stock in the company recently worth $260 million. In another example, Conway flew to Brazil to help Talaris, a British portfolio company that makes ATMs and other cash-handling equipment, become a client of Banco do Brasil, a Carlyle fund partner. Earlier this year, Carlyle sold Talaris to a Japanese company, making $540 million in profits in less than four years.

Carlyle’s global approach comes together fully in China, which is currently home to one-sixth of its workforce. Carlyle raised its first of three Asia-focussed buyout funds in 1999 and has set up two yuan-denominated funds with Chinese partners. China has already produced blockbuster deals for Carlyle, including its investment in China Pacific Insurance, one of the greatest private equity deals ever. In 2005, Carlyle made a $738 million bet that the largely uninsured Chinese population would buy risk protection as the economy boomed, resulting in a $5 billion windfall for its investors. Conway has become more concerned about the slowing Chinese economy and thinks it will be harder to duplicate this kind of success. These days, he sees more opportunities back in the US.

Not surprisingly, Rubenstein argues that private equity is also a good thing for America, pointing out it’s a massive financial industry based in the US.

He likes to say he is better received in Beijing these days than in Congress, where he tells sceptical lawmakers to consider not doing anything to damage one of the few global businesses the US still dominates. On the issue of carried interest—the application of lower capital gains taxes on private equity performance fees—Rubenstein presents a nuanced defence. “It’s unfair to single out any one industry when it comes to tax reform. Let’s have a comprehensive look at everything,” says Rubenstein. “Don’t spend all your time changing the private equity rules, because you aren’t going to pick up any revenue. Maybe that means increasing capital gains taxes, maybe marginal rates. Everything should be on the table.”

Ironically, one of the toughest recent sales jobs for the master fundraiser was convincing people to invest in Carlyle’s own IPO, even though all the money raised was slated to pay off debt. Part of the problem was that Carlyle’s earnings have historically been lumpy, coming more from episodic performance fees. Wall Street doesn’t like the kind of results Carlyle posted in its last quarter, when it reported an economic net loss of $58 million.

Investors are also suspicious of private equity shops because these companies are partnerships whose first allegiance is to the investors in their funds, not in their firms. Many stock investors had already been burned by the IPOs of Blackstone, Fortress Investment Group and Apollo. Carlyle is out to prove these stocks can work for investors. To sell the IPO, Carlyle cheaply priced its shares even cutting the final price by half a buck on the demands of a major investor. Rubenstein couldn’t believe it when he heard that same investor bought $1 billion of Facebook stock at $38 the same month.

As always, though, Rubenstein got the deal done.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)