The Gardasil Problem - The Wasted Vaccine

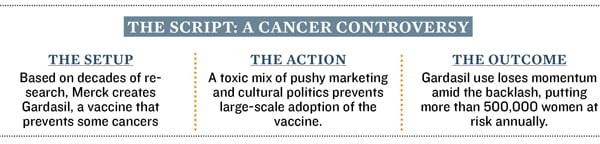

US politics and Merck's bad public image are keeping a breakthrough vaccine from saving hundreds of thousands of lives around the world and endangering the cures of the future

Neal Fowler, 50, the chief executive officer of a tiny biotech called Liquidia, was assuming a position common to road-warrior entrepreneurs: Leaning his elbows on the seat-back tray in an airplane so he could gaze at the screen of his laptop. That’s when he felt the lump in his neck.

Fowler, a pharmacist, figured his lymph node was swollen by a recent cold, but the oncologist seated next to him—his chairman of the board— thought they’d better keep an eye on it.

The chairman was right. Over the next week the lymph node got bigger and harder. It was not sore to the touch, as happens during a cold. Fowler went to the doctor, then a specialist who knew exactly what he was seeing: A new form of throat cancer that ear, nose and throat specialists across the US now say dominates their practices. Some 8,000 of these tonsil tumours turn up each year nationwide, courtesy of strain 16 of the human papilloma virus—the same sexually transmitted virus that causes cervical cancer.

His prognosis was good—80 percent of those with this new tumour survive. His status as a drug industry veteran and chief executive of a biotechnology company didn’t hurt, either. He went from diagnosis to having the primary tumour removed from his tonsil in just a day. His first team of doctors wanted to do a second surgery, opening up his neck, but by polling other experts he found a different team and a different option: Chemotherapy and radiation.

But it gnaws at Fowler, who thinks about vaccines all day long that one that might prevent other boys, including his teenagers, from ever developing this cancer isn’t being used. Gardasil, one of two HPV vaccines, is already approved in boys to prevent anal and penile cancers, but because these diseases are rare, only 1 percent actually get it. And tests that might well prove that this Merck product can prevent the new throat cancer strain would take at least 20 years, until the boys sampled actually became sexually active and then contracted the disease. “We’ve got this two-or three-decade window where more and more of these patients like myself are going to emerge,” says Fowler. “To me the [vaccine] risk is minimal, and I’d say, why not do that? A big part of the answer is politics. Drug safety, vaccines, antibiotics and reproductive medicine—all have become proxies for the culture war, often tripping up public health in the process. Big Pharma hasn’t helped, with deep PR wounds that have made it anathema to both political parties.

Nor has the FDA, which has shifted the goalposts on approving new antibiotics enough to scare away many innovators just as resistant bacteria have become a big health problem. Both parties undermined the FDA further by overruling it on how the Plan B emergency contraceptive should be used, weakening the agency’s authority. Now a coalition on the right is pushing to remove all testing of whether some medicines are effective, while many on the left still think the FDA remains too cozy with the drug industry.

“If you look at both sides of the political spectrum I’m amazed and appalled by the lack of knowledge that’s being put forward as knowledge,” says Robert Ruffolo, former head of research at Wyeth. “They’re not scientists, they’re not physicians, and many politicians will say almost anything during election season.”

Nothing underscores that point more than what has happened to Gardasil, a vaccine with an exceptional safety record and effectiveness rate that nonetheless reaches a fraction of those who need it, endangering hundreds of thousands of lives in both the developed and developing world. Besides the paltry numbers for boys, only 30 percent of eligible girls get Gardasil or a rival product, Cervarix, made by GlaxoSmithKline.

For many on the right the issue is promiscuity. Because HPV is usually transmitted through sex, it is viewed as a permission slip for lasciviousness.

For many on the left the issue is the big, bad drug companies. Merck lost credibility through its aggressive tactics marketing Vioxx, an arthritis pill that turned out to cause heart attacks. But now that taint hinders the prospects for all their products, notably Gardasil. And both sides increasingly embrace the narrative that vaccines, one of the great success stories of modern innovation, are somehow unsafe. In many ways they’re just channeling their voters: A Thomson Reuters/NPR Health Poll last year found one in four Americans believes there are safety problems with vaccines, which experts say are among the safest medical products ever created.

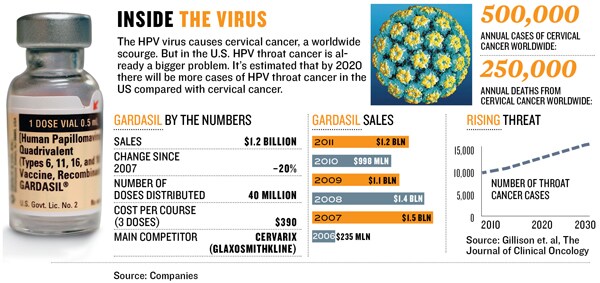

Launched in 2006, Gardasil sales immediately shot to $1.5 billion in 2007 before the poisonous politics clipped it back. By 2010 sales fell to nearly $1 billion. Last year sales crawled back a bit, to $1.2 billion.

But 2011 was still a very bad year for Gardasil. In September, as the Republican presidential candidates jostled for position, Representative Michele Bachmann attacked Texas Governor Rick Perry for being the first major politician to mandate Gardasil use. Rather than simply point out his ties to Merck or question his authority to do it, Bachmann asserted that Gar- dasil was dangerous and, on TV the next day, claimed she’d met a mother whose daughter had become “men- tally retarded” because of the vaccine.

Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, calls the episode “disastrous.” “It’s an insult that people are not looking at the evidence,” says Brawley. “It’s a tragedy that we could prevent people from dying from cervical and head and neck cancer but our society just can’t bring itself to have an open, rational, scientific discussion about the facts.” Bachmann did not return multiple requests for comment.

It’s a sad predicament for a drug with such a distinguished and promising history. Gardasil sprang from the 1976 discovery that cervical cancer tumours were caused by the human papilloma virus. Harald zur Hausen, a German scientist, won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology & Medicine for this discovery. The Nobel Prize committee noted that HPV might play a role in 5 percent of human cancers and at least half of the people get HPV at some point in their lives.

But making a vaccine wasn’t possible until researchers at the National Cancer Institute figured out how to make “virus-like particles” that mimicked the outside of the HPV virus without actually containing viral DNA. This technology was licenced to Merck and GlaxoSmithKline.

At Merck a microbiologist named Kathrin Jansen was put in charge of knitting together several technologies in order to turn this innovation into a successful vaccine. Now a researcher at Pfizer, Jansen says she is disheartened by the political battle over the vaccine.

“It becomes frustrating to vaccine researchers when successful vaccines are being developed and then they are not used in a setting that really makes the best use of them,” says Jansen. “What always irks me looking at Gardasil is if you look at the target population, it’s just 25 percent to 30 percent that are being immunized. So that’s usually not sufficient to really have a substantial impact.” If the vaccine were widely used, she says, it might not only prevent cervical cancers but also some cases of throat cancer, as well as a rare disease in children where warts have to be constantly removed from their throats. “They have surgery after surgery. Well, you’re not using the vaccine in that population. You could drive it away! I mean there is no reason why we should still have all that disease. That’s what irks me.”

Merck bears more than a little responsibility for the negative response to Gardasil. When it was introduced in 2006, Merck was still reeling from the 2004 withdrawal of Vioxx and the resulting flood of lawsuits. Instead of going slow, as many of its own advisors recommended, Merck began an advertising push to raise awareness of the risks of HPV and began lobbying state governments to make Gardasil shots mandatory. Perry was the first to sign on. Virginia, which originally voted to make HPV vaccines mandatory, recently reversed the vote. Merck would have done better to take a stance like that of the American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, which strongly recommends HPV vaccines for 11- and 12-year-old girls but says they should not be mandatory.

“It would not have been the way the old Merck would have done business,” says David Kessler, who ran the Food & Drug Administration from 1990 to 1997. “It was a science-based company, not a marketing company. They would have been able to educate the medical community about the benefits, and the medical community would have adopted the product over time.”

The company seems to agree. “Merck suspended our lobbying five years ago because our involvement became a distraction, and we believed the focus should be on the battle against cervical cancer,” a spokeswoman says. The data indicate Gardasil is actually an exceptional drug, extremely safe and extremely effective. In clinical trials of 30,000 people, potential side effects ranging from fever to death occurred at the same rate whether patients were given a saline solution placebo or Gardasil. Deaths occurred in only 0.1 percent of people in either group. Since the vaccine was approved, it has been given to at least 10 million people, mostly teenage girls. The FDA and the CDC have received reports of 71 deaths of people who got the vaccine and, on examining them, found no pattern.

They looked specifically at the terrible neurological disease called Guillain-Barré Syndrome, because it’s known that a swine flu shot given in the 1970s caused it. The rate of GBS reported for Gardasil was half what it was for other vaccines, meaning that Gardasil probably wasn’t causing any elevated risk of the disease.

The biggest victims of America’s Gardasil war don’t actually live in America, though. They live in the developing world, where cervical cancer infects some 500,000 women and kills half of them every year. In the US the number of cases of cervical cancer is controlled by the fact that women get regular Pap smears. Among the most effective cancer screening tests ever invented, they catch precancerous growths before they turn into tumours.

Women in the developing world, and in poorer parts of the US, lack this safety net. The GAVI Alliance, the vaccination effort started by Bill Gates, is working with Merck and GlaxoSmithKline to try to lower the prices of the vaccines and separately to raise money to get them to these women. But it’s tougher to raise money in a political firestorm, and there’s also worry that the women whom GAVI seeks to help will be scared by the bad press in the US. “It certainly hasn’t helped that we have political candidates who stand up with irresponsible comments,” says Seth Berkley, chief executive of GAVI.

One person who has vowed to make sure HPV vaccines get to all the people who need them is Julie Gerberding, the head of the CDC under George W Bush and since 2010 the head of Merck’s vaccine business. She says she came to Merck because Chief Executive Kenneth Frazier promised her that his aim was to get medicines “to the people who need them most”—not just those in the developed world.

In Uganda, just after she joined Merck, she visited an AIDS clinic. A young woman started to bleed from her cervix and “literally almost bled to death in front of my eyes,” says Gerberding. “You know they don’t have blood transfusion, they don’t have the kinds of easy access emergency care that we would have, and, of course, she was dying of undiagnosed cervical cancer.” Gerberding says she is committed to finding a way to get Gardasil—or a successor vaccine that Merck will submit to the FDA this year that will protect against more strains of HPV—to all the women and men who need it. She says she’s committed to reexamining studies into the throat cancer link as well. For the Neal Fowlers of the future—and the rest of us—that moment can’t come soon enough.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)