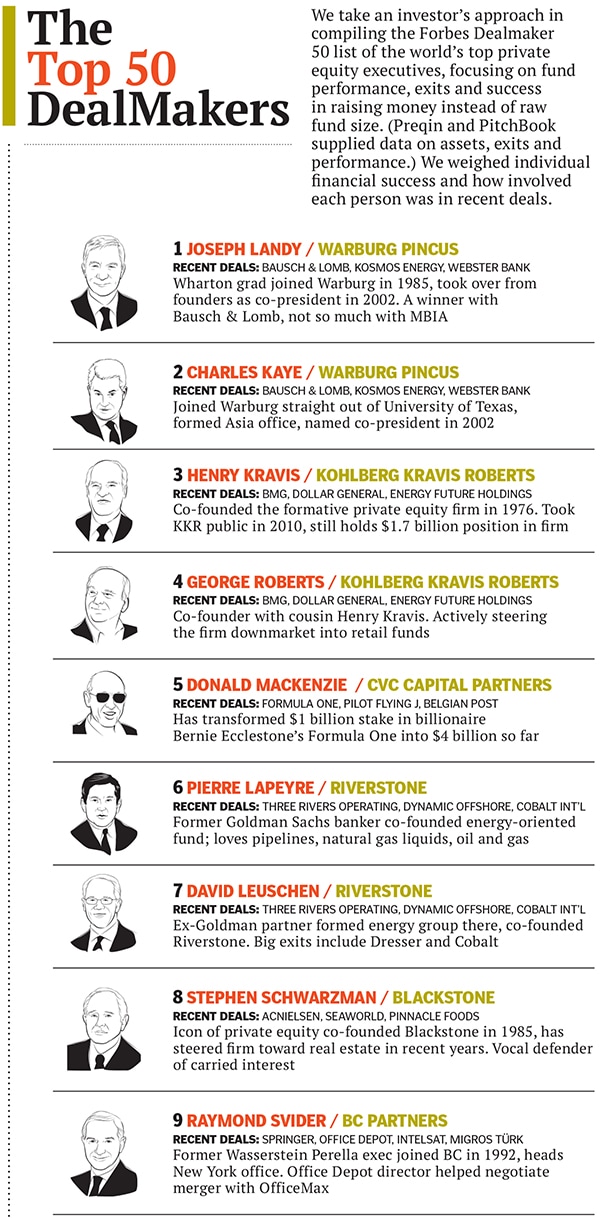

The Dealmakers at Warburg Pincus

Warburg Pincus hasn’t morphed into a financial supermarket like the giants of private equity. Perhaps that’s why its dealmakers top our ranking of private equity’s biggest hitters

For their biggest deal ever, the team running Warburg Pincus started with epically atrocious timing. Their October 2007 purchase of Bausch & Lomb for $4.5 billion was almost precisely at the market top. Within 18 months the market had been halved.

Their due diligence proved even worse. “It was a great surprise to learn how bereft the company was of any valuable internal product development,” says Warburg’s co-president, Joseph Landy, from his sleek, airy wood-glass-and-steel office in midtown Manhattan, describing what it was like to enter Bausch & Lomb’s Rochester, New York, headquarters. Not only was the optical goods manufacturer battling accounting scandals in Brazil and Spain, but it had also been sued by hundreds of customers injured by a defective batch of MoistureLoc contact lens solution. The company had badly damaged its 150-year-old brand name, and products like a promising hydrogel contact lens that customers could wear for a month had languished for lack of development capital.

So Warburg went to work. It immediately installed former Schering-Plough chief Fred Hassan as chairman and his lieutenant Brent Saunders as chief executive—Bausch & Lomb’s third in three years. The duo cleaned house, keeping only two of 17 top executives. They then acquired new businesses like Eyeonics, a cataract lens maker, and refilled Bausch & Lomb’s product pipeline.

Six years later, in May, Warburg sold the company to Canada’s Valeant Pharmaceuticals for $8.7 billion. On a deal that had begun as auspiciously as the Titanic, Warburg doubled its money.

That kind of roll-up-your-sleeves performance, turning even the deals that look like dogs into winners, has landed Landy and co-president Charles “Chip” Kaye atop this year’s Forbes Dealmaker 50 list, which ranks the top-performing executives in private equity. Warburg Pincus, with more than $40 billion in assets under management, isn’t anywhere near being the biggest among private equity firms—it was long ago eclipsed by the giants like TPG Group ($55 billion) and KKR ($84 billion). But what Landy and Kaye lack in size they more than make up for in smart deal selection, hard work and profitable exits.

While others in the business have expanded their financial offerings— from renewable energy at Carlyle to retail junk bond mutual funds at KKR—Warburg has kept its head down, sticking to the basic blocking and tackling of the buyout business, avoiding 10-figure megadeals. Often it acts more like a venture capital firm, buying big into small, unproven companies.

Warburg didn’t go public like Blackstone and the Carlyle Group during the recent wave, and it participated in few of the ‘club deals’ with other PE firms that are now dragging down the results of shops like Bain Capital and TPG. Warburg also doesn’t charge its portfolio companies ‘management fees’ for the pleasure of being owned by Warburg or ‘deal fees’ for arranging the loans that private equity partners use to pay themselves dividends. Breaking into specialised subdivisions? “It’s not who we are,” says Kaye, who insists that each Warburg fund be diversified with the entire range of firm investments, from venture capital to leveraged buyouts. “The question is: Do you sell what you know how to manufacture, or do you manufacture what you know how to sell?”

That decided lack of flash is ironic, since Warburg Pincus might have the best corporate pedigree on Wall Street, with roots dating to the famous Warburg banking family of Europe, which began amassing wealth in the early 1500s in Venice. Eventually this clan of Jewish merchants settled in Warburg, Germany, and its descendants became prominent in European commerce, arts and philanthropy. Eric Warburg started his investment firm EM Warburg in downtown New York in 1939, and much to the disappointment of his cousins in Germany, he struck a partnership in 1966 with financier Lionel Pincus, a Columbia Business School graduate whose family emigrated from Russia and Poland and had been in the rag trade.

After Eric Warburg retired back to Germany in the mid-1960s, Pincus and another partner, John Vogel- stein, specialised in what is now called venture capital, supplying funds to small companies in their rapid-growth phase. Warburg raised a then-astounding $41 million for its first investment partnership in 1971 and the industry’s first $100 million fund in 1981. Notable early deals included Twentieth Century Fox, Humana and Mattel.

Landy, 52, a Baltimore native and Wharton grad, joined the firm in 1985 after a brief stint with Dean Witter and quickly built a reputation for investing in technology companies. Kaye, 49, joined Warburg straight out of the University of Texas and moved to Hong Kong in 1994 to build its Asia operation, which has since invested $6.5 billion. The two took over in 2002 after a long period in which older partners waited in vain for Pincus and Vogelstein to retire; unlike David Bonderman of TPG or Leon Black of Apollo, they hold relatively small stakes in the firm, with ownership spread across 60 partners.

Unintentionally, this keeps them aligned with their investors—they need wins, rather than matching the market or skimming fees from a large asset base, to score big money.

Not coincidentally, Warburg excels at handing money back to its limit- eds. The firm has distributed more than $15 billion since the beginning of 2012. Fund analyst Preqin says the 10 Warburg funds it tracks rank in the top half of performance, with four in the top quartile, the highest percentage among the largest 50 firms Preqin monitors. Warburg’s 2000-vintage international fund has generated an internal rate of return of 33 percent on $2 billion in commitments, and its 1994 fund turned in an astounding 50 percent return thanks in part to the 1990s technology boom and the continued emphasis on mixing in early-stage investing. Warburg’s $54 million investment in a software startup called BEA Systems, starting in 1995, wound up being worth $6.8 billion; the firm similarly converted a $8 million investment in Covad Communications into $1 billion in two years. The firm has also kept up a long, successful streak in energy, spearheading the likes of Spinnaker Exploration, New- field Resources and Kosmos Energy.

One recent blemish on Kaye and Landy’s record has been its $15 billion Fund X. Since 2008 it’s logged a 6.7 percent return, due in part to timing and bad bets like its $1.2 billion investment in mortgage insurer MBIA. But Warburg’s funds typically run for 12 years or more, and thanks to its track record Warburg was able to attract $11 billion for its 13th fund, which closed in May.

Those new investors are counting on the gumption typified by the Bausch & Lomb deal. The bad tim- ing and unpleasant surprises were mitigated by a growing health care business—which is largely immune to price-controlling bureaucrats—and the discount that came with a troubled recent history.

“The thesis there was to take a company which had an unbelievable brand but basically had been ignored because of distractions that caused them to take their eyes off the ball,” Landy says.

It’s those kind of smaller deals—versus TPG’s $45 billion takeover of Texas utility Energy Future Holdings or Bain’s $24 billion buyout of Clear Channel Communications, both of which are deeply troubled—that keep Warburg from wanting to grow out of control. Says Kaye, “The days when simply having a lot of capital was differentiating unto itself have passed.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)