The big picture: Instagram is driving Facebook's future

Instagram is emerging as Facebook's growth engine, turning Mark Zuckerberg's purchase into one of the greatest tech deals of all time. But no tears for the photo-sharing app's co-founder, Kevin Systrom. He's building an empire—and just made himself a billionaire

With 9.6 million Twitter followers, 79-year-old Pope Francis might be the most surprising breakout star of the social media age. Keen to reach a younger generation, the pontiff summoned a person with a platform that rivals even the Catholic Church when it comes to Millennial members: Kevin Systrom, CEO of the photo-sharing app Instagram, which has more than 500 million users, including 63 percent of US Millennials.

Ever the shrewd pitchman, Systrom, 32, brought a gift to their February meeting at the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, something that was both thoughtful and promotional: A booklet of ten Instagram images—a peaceful protest, refugees, a lunar eclipse—touching on themes close to the Pope’s heart. “He mentioned how when he talks to children they don’t necessarily speak his language, but they will show him pictures on their phones, and how that’s the most powerful way of communicating,” says Systrom, who readily admits he isn’t “as religious as a lot of people in the world.”

But the two found themselves singing from the same visual hymnbook. Three weeks later, Systrom was again on a flight to Rome. “When I saw the Pope the second time, he was like, ‘Keviiinnn!,’ as if we had gone to college together, like we played at the same golf club or something,” he says. As the 6-foot-5 Systrom, clad in an Italian suit, stood over him, the Pope officially joined Instagram as @franciscus, posting an image of himself kneeling, with the caption “Pray for me” in nine languages. It’s been “liked” 327,000 times.

Since then, Instagram has become the place to get an intimate look inside the Holy See. A world that was previously cloistered and out of reach now shows @franciscus blessing dogs at St Peter’s Square, comforting the sick, walking alongside African refugees and even smiling for selfies with worshippers. In just four months, he’s amassed 2.8 million followers, or nearly a third of his Twitter audience, which he’s been cultivating for about four years.

Almost as telling is how many Facebook followers the Pope has: Zero. He still hasn’t debuted there, content to message his flock via Twitter and to share his life—and reach Millennials—via Instagram.

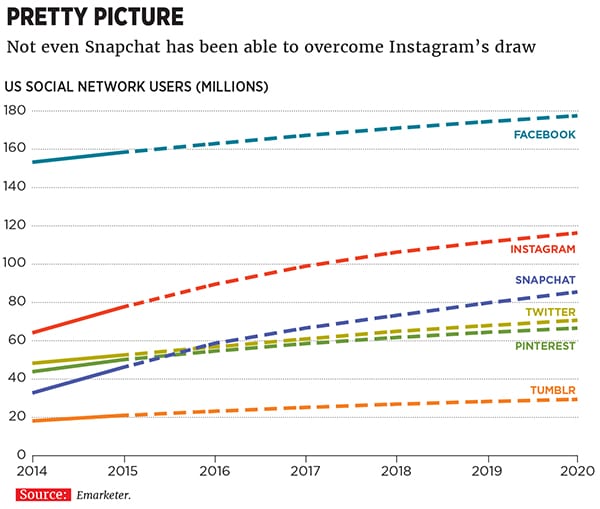

And that suits Mark Zuckerberg just fine. When Zuckerberg decided to shell out nearly $1 billion in 2012 to buy the photo-sharing app, which had just 30 million users, it was widely seen as a sign of a new Silicon Valley bubble. But he appears to have outsmarted everyone once again. In the four years since the purchase, Instagram has become one of the fastest-growing platforms of all time, with about as many users as Twitter (310 million), Snapchat (100-million-plus) and Pinterest (100 million) combined.

And while Facebook’s other big (and more expensive) acquisitions—message service WhatsApp and virtual reality pioneer Oculus VR—also draw eyeballs and buzz, respectively, Instagram generates revenue: About $630 million in 2015, according to eMarketer.

Of course, this is small beer compared to the Facebook juggernaut, with its 1.7 billion users and $18 billion in sales. But if we’ve learnt anything in the digital age, a ubiquitous service, whether it’s Yahoo or AOL or BlackBerry, can wither on a dime when the next cool platform comes along. Ask anyone under 18 (a cohort who view Facebook as their parents’ social network): Instagram is that next platform. Systrom and his lean team are future-proofing Facebook, in the process proving Zuckerberg’s purchase was one of the five best deals of the internet era. Forbes estimates that Instagram, if broken out, is now worth somewhere between $25 billion and $50 billion.

And that number is poised to rise. As Facebook shows signs of saturation, Instagram added its latest 100 million users in nine months. Sales this year are expected to nearly triple, to $1.5 billion, and triple again, to $5 billion, by 2018 (according to eMarketer).

And the most remarkable (and profitable) part of all is that Instagram is still run as a skunkworks within Facebook: Its 350 employees make up slightly less than 3 percent of Zuckerberg’s 13,600-person army. “The combination of this visual opportunity to tell your story as a person, a marketer and a business, combined with the ability to target the audience, has been very powerful,” says Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg. “Kevin’s leadership has been the driver.” Like any company of its size, Facebook is becoming unwieldy. In Instagram and Systrom, Zuckerberg retains an entrepreneurial engine.

Within Facebook’s Menlo Park campus, Instagram has carved off its own bunker, deliberately set across the street and a short bike ride from the mother ship. The office is decorated with large posters of Instagram photos selected by staff: Mount Everest, Oakland’s Lake Merritt, latte art. Another wall is covered with a collage of giant fingerprints. Systrom also differs from Zuckerberg in personal style, preferring stylish shoes and nice suits to Zuckerberg’s hoodies and tight T-shirts, and carrying himself with a self-deprecating ease that contrasts with Zuckerberg’s more strained demeanour.

Such differences aside, Systrom’s path to Facebook seemed preordained. In 2005, Zuckerberg tried to persuade him to skip his senior year at Stanford and launch a Facebook photo service. Systrom declined, costing himself what surely would have been tens of millions in stock options. He wound up working in a coffee shop (where he famously once had to serve Zuckerberg), then at Google and the startup Odeo. Inspired by location-based apps like Foursquare, Systrom and his friend Mike Krieger launched the mobile check-in game Burbn in 2010. Systrom soon pivoted to a photo app, creating the first filter, X-Pro II, while on vacation in Mexico. More filters followed. Users did, too—by the millions.

But even then, Instagram ran lean. It had just six employees its first year and 13 when it sold to Facebook. “Most companies that serve half a billion people have thousands of people. We’re still in the hundreds, so we have to focus,” Systrom says. “It’s prioritising that makes us efficient and makes us succeed.” Simple has always been Systrom’s credo.

Instagram’s road to mass adoption has come through an intuitive app that has easy editing tools and a set of filters that allow anyone to turn smartphone photos and videos into edgy, nostalgic, glamorous, intimate or dramatic visual diaries. Instagram filters transform everyday life into an airbrushed ideal—personal advertisements to share with friends and fans.

Today virtually every public figure, from Aziz Ansari to the Dalai Lama to Taylor Swift, is active on Instagram. Athletes treat it like a second scoreboard. When soccer superstar Lionel Messi passed 30 million followers in December, Stephen Curry made headlines for sending him a signed Golden State Warriors jersey with his No 30 emblazoned on the back. Messi returned the favour a few months later with his own signed Barcelona No 10 jersey when Curry passed the 10 million mark.

But Instagram is far more than a vehicle for celebrities to cut out the paparazzi and go directly to their fans. What Systrom calls the app’s “superpower” is its ability to cater to the hyperspecific passions and obsessions of a wide range of interest groups. Users have rallied around visual hubs dedicated to Korean light shows, artisanal cheese shops, skateboarding tricks (Tony Hawk is an active user), break dancing and extreme body painting. Every day, users spend more than 21 minutes on average in the app and collectively upload more than 95 million photos and videos.

That sticky engagement is reshaping entire industries. Look no further than fashion. This year, designer Misha Nonoo, whose modern women’s clothing has been worn by Emma Watson and Gwyneth Paltrow, ditched the runways of New York Fashion Week and launched her spring 2016 collection with Aldo Shoes exclusively on Instagram. Systrom’s team helped Nonoo prep a new account for her “InstaShow”, letting fans scroll through dozens of her looks inside the app. Nonoo replaced 20 models and an expensive set with three top models and a smartphone. The experiment worked beautifully, driving more traffic to her site than any runway event ever had—and for only 65 percent of the cost.

Nonoo is hardly alone among fashionistas. This year, Tommy Hilfiger created an “InstaPit”, which gave influential Instagrammers prime seating at his show so they could capture the best shots and share them with their followers. And at this year’s Met Ball, Vogue’s Anna Wintour, who has become pals with Systrom, hosted an exclusive Instagram video studio, where A-list celebrities like Madonna and Blake Lively posed for photos and clips on the app. In all, the coziness between the fashion world and Instagram generated 283 million engagements—likes and comments—across 42 million accounts during four weeks of shows early this spring in New York, London, Milan and Paris.

Instagram’s reach extends far beyond fashion. In 2014, Wal-Mart even added Systrom to its board to harness his digital expertise. Brands ranging from fast food to big banks advertise on Instagram to take advantage of the site’s unique features. At this year’s Coachella, Sonic Drive-In made special square-shaped milk shakes for a single-day Instagram campaign. A “Shop Now” button on the ads let people place an order, which Sonic delivered on the spot. More than three-quarters of festivalgoers who clicked on the “Shop Now” button purchased a shake. Says Todd Smith, Sonic’s president and chief marketing officer: “We wanted to present the shakes in a different way that would work only on Instagram.”

In all, more than 200,000 companies are now advertising on Instagram, up from just hundreds last June. A Nielsen study of more than 700 campaigns found that for 98 percent of them, ad recall from sponsored posts on Instagram was 2.8 times higher than average for online advertising. It’s the kind of effectiveness that lured the TV Land network to Instagram to promote Teachers, which led to a 21 percent increase in awareness of that series. And it’s what convinced the music-venue chain House of Blues Entertainment to use Instagram’s direct response ads to sell tickets for artists performing at the Fillmore in Charlotte, North Carolina. “Instagram is one simple visual feed. The focus is each piece of content,” says Mikey Kilun, House of Blues’ director of digital and social strategy. “When I go on Facebook, I’m distracted by so many things.”

If Zuckerberg made one of the great deals in recent history, then it would follow that Systrom made one of the worst. That $1 billion price tag might well have been ten times as large if he’d waited a year or two.

Two mitigating factors in Systrom’s defence: First, Forbes estimates that Systrom, who got mostly Facebook stock in the purchase, can now join the Billionaires List with an estimated net worth of $1.1 billion. Not too shabby and a lot better than if he’d taken Zuckerberg’s first job offer a decade ago.

Second, Facebook has accelerated Instagram’s growth massively. “It’s because of Facebook we were able to get to this scale,” says Systrom. “Instagram was growing quickly on its own, but it was good to have that rocket booster.” By working inside the social media giant, Instagram could draft off its billion-plus members, exploiting its technology, top-notch infrastructure and engineers, and massive sales force. “This is having Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson on the same team,” says NYU marketing professor Scott Galloway. Facebook’s Sandberg echoes the sentiment: “Combined, Facebook and Instagram own more than one out of every five minutes you spend on a mobile phone. Together we’re the best ad platform by far.”

Being a company within a company has its advantages. In addition to weekly chats with Zuckerberg, Systrom frequently consults with the leaders of Facebook-owned units WhatsApp and Oculus, plus executives like Sandberg, chief technology officer Mike Schroepfer and chief product officer Chris Cox. “One of the things I love about working here is I get to sit in a room with all of those people, and we all can help each other, and we all can learn from each other,” Systrom says. “We have very different businesses, but a lot of the same challenges exist—regulation, shifts in the creative ecosystem, what tools people value, how people want to communicate. We face a lot of the same competitors.”

To stave off competition, Facebook lends Instagram its sales operation, offering access to more than 3 million advertisers, ad tech, relevance algorithms, spam-fighting tools and, perhaps most helpful, unparalleled user data (on interests, gender, location, occupation and more). For marketers, extending Facebook ad campaigns to Instagram is seamless—

98 of the top 100 spenders on Facebook are on Instagram, too.

But for all Instagram and Facebook share, they diverge on a key cultural trait. Facebook’s mantra is “Move fast and break things.” Instagram’s core maxim could be “Handle with care.” It’s a value that’s defined the company since Systrom and Krieger started it. “Kevin only wanted to hire people who were as committed to the product as he was,” says Steve Anderson, the founder of Baseline Ventures and Instagram’s first investor. “He held to that standard. You could argue it might have slowed the growth of the company, but it ended up being the right decision.”

The tortuous pace extended to advertising. Systrom built the business cautiously, ensuring that marketers didn’t overwhelm and turn off users. Even as advertisers were clamouring to get on board, Systrom opened the spigot gradually, testing the first round of ads to make sure they jibed with Instagram’s audience before inviting a larger set of clients. Its first ad, in November 2013, was from Michael Kors—the kind of luxury goods brand that might have advertised in a glossy magazine and was attracted to the similarly clean and visually arresting Instagram interface. Until late 2014, Systrom—taking a page from Vogue’s Wintour—personally reviewed every ad in a print booklet before giving the green light.

Instagram has since branched out beyond photo ads, debuting video and carousel ads, opening its ad platform widely across more than 200 countries and lengthening video ads to 60 seconds. Still, an internal team continues to work with advertisers to create captivating ads that still feel like a natural part of the app. “Not everyone loves ads, but our ads have gotten so much better from day one,” Systrom says. “People hate irrelevance more than they hate advertising.”

Systrom might move slowly, but he’s not stubborn. Over the years he’s made countless product changes, adding direct messaging and hashtags for topics and places, creating an “Explore” tab for following trends, and adding videos. But unlike Facebook, which launches and shutters many experiments (apps like Paper and Slingshot and Rooms), Instagram has been more careful, releasing only four separate apps so far, including Boomerang, for creating one-second GIF-like looping video clips; Layout, for collages; and Hyperlapse, for time-lapse videos. (Bolt, a messaging service Instagram tested in a few countries outside the US, fared worse and has been shuttered.)

The natural evolution of Instagram points to video. Tech companies like Google, Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest have already yanked away advertising dominance from old-line print media. With roughly $70 billion bleeding out of the TV advertising business and onto iPhones, every content company is racing to own mobile video. Video-first networks like YouTube, Vice and Snapchat have a big head start. For Instagram to catch up, it needs to perform a delicate balance—push hard into video without alienating the 500 million users who come for the still images. Instagram’s video advertising programme, which was launched in 2014, accounts for just 19 percent of the ads on the platform, according to research firm L2.

Krieger, a fellow Stanford alum who runs Instagram’s backbone as chief technology officer, says his co-founder’s caution has always been balanced by a strong point of view about where he wants to go. Throughout the company’s history Systrom faced internal resistance when championing several of the app’s biggest changes. Employees pushed back when he proposed adding video-sharing in June 2013, when he advocated moving beyond the app’s trademark square images into portrait and landscape shots, and this year when Instagram rolled out an algorithmic feed that selects content by relevance rather than chronology. “The idea of adding video to Instagram honestly freaked a lot of our employees out,” Krieger says. Systrom tackled the challenge like a reassuring parent: He acknowledged the move was scary but convinced his team he wasn’t about to drive them off a cliff. “He’s willing to make the calls that move the product forward, even when it’s not obvious or immediately popular,” Krieger adds. Systrom himself is sanguine about his deliberate and stepwise approach: “The good news is it’s working so far.”

It’s working especially well for Facebook. This year Zuckerberg laid out a three-year, five-year and ten-year vision for his company. Facebook itself dominates the first chapter. The second focuses on Instagram and other products like Messenger and WhatsApp. While the last two are vastly popular (with 1 billion users each) and may well become large businesses someday, neither generates sizeable revenue so far. That leaves Instagram, at least for now, as the force that will turbocharge Facebook as it drives toward Zuckerberg’s ten-year horizon, when new products based on virtual reality and Artificial Intelligence will reshape social media, communications and computing in ways still unknown.

Technology changes, but Systrom’s original vision for Instagram remains: Create a visual record of everything happening around the world at any time, allowing users to zoom in to any corner of the planet they wish to explore. To hit that goal, Systrom envisions doubling the number of users to a billion or perhaps even tripling it, building an audience that rivals Facebook itself. “We had to remind ourselves to celebrate 500 million users,” says Systrom. “To get to this scale is a mark, not a badge on our uniform but a signal of our ambition. We’re obviously not stopping now.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)