The Barons of casino capitalism

By hooking disillusioned millennials on its zero-commission, gamified trading app, Robinhood has forever changed the retail brokerage business. "Democratising finance" is the stated goal, but its founders have become billionaires by leading a new generation of rubes right into the jaws of Wall Street's most notorious sharks

Taking the Wager: Robinhood co-founders Baiju Bhatt (left) and Vladimir Tenev

Taking the Wager: Robinhood co-founders Baiju Bhatt (left) and Vladimir TenevIlluustration: Lars Leetaru

Just after midnight on Friday, July 31, and the Todd Capital Options Community, a $20-per-month subscription Slack channel favoured by thousands of novice options traders, is buzzing with life. Unemployment is soaring and governments worldwide are desperately trying to fend off economic collapse. But members of this online enclave are partying, quite literally, like it’s 1999—the infamously frothy day-trading year before the dot-com bubble burst in March 2000.

Despite the pandemic, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google have just released jaw-dropping financial results, a staggering $205 billion in combined quarterly sales and $34 billion in earnings during a stretch when US gross domestic product plunged at an annualised rate of 33 percent. For weeks, the club’s youthful members have been loading up on speculative call options using the mobile trading app Robinhood. Now they’re ready to cash in.

“Literally, NOTHING will make me sell my AMZN 10/16 calls tomorrow. I don’t care what happens. . . . I’m holding everything. Keep ya boi in your prayers,” says one user named JG. As dawn approaches, “NBA Young Bull” announces: “Good morning future millionaires . . . is it 9.30 yet?”

For these speculators, the adrenaline rush turned to euphoria after Apple not only beat earnings expectations, but announced a 4-for-1 stock split, luring more small investors to the iPhone maker’s stock party. At 9.30 am Friday, when trading begins, the call options on Apple and Amazon held by many of these market newbies pay out like Las Vegas slot machines hitting 7-7-7 as both tech giants gain a collective quarter-trillion dollars in market value. Throughout the day and over the weekend, a stream of posts scroll by from exuberant Robinhood traders going by screen names like ‘See Profit Take Profit’ and ‘My Options Give Me Options’. On Monday, August 3, the Nasdaq index sets a new record high.

Welcome to the stock market, Robinhood-style. Since February, as the global economy collapsed under the weight of the coronavirus pandemic, millions of novices, armed with $1,200 stimulus cheques, have begun trading via Silicon Valley upstart Robinhood—the phone-friendly discount brokerage founded in 2013 by Vladimir Tenev, 33, and Baiju Bhatt, 35.

They built their rocketship by applying the formula Facebook made famous: Their app was free, easy to use and addictive. And Robinhood—named for the legendary medieval outlaw who took from the rich and gave to the poor—had a mission even the most woke, capitalism-weary Millennial could get behind: To “democratise finance for all”.

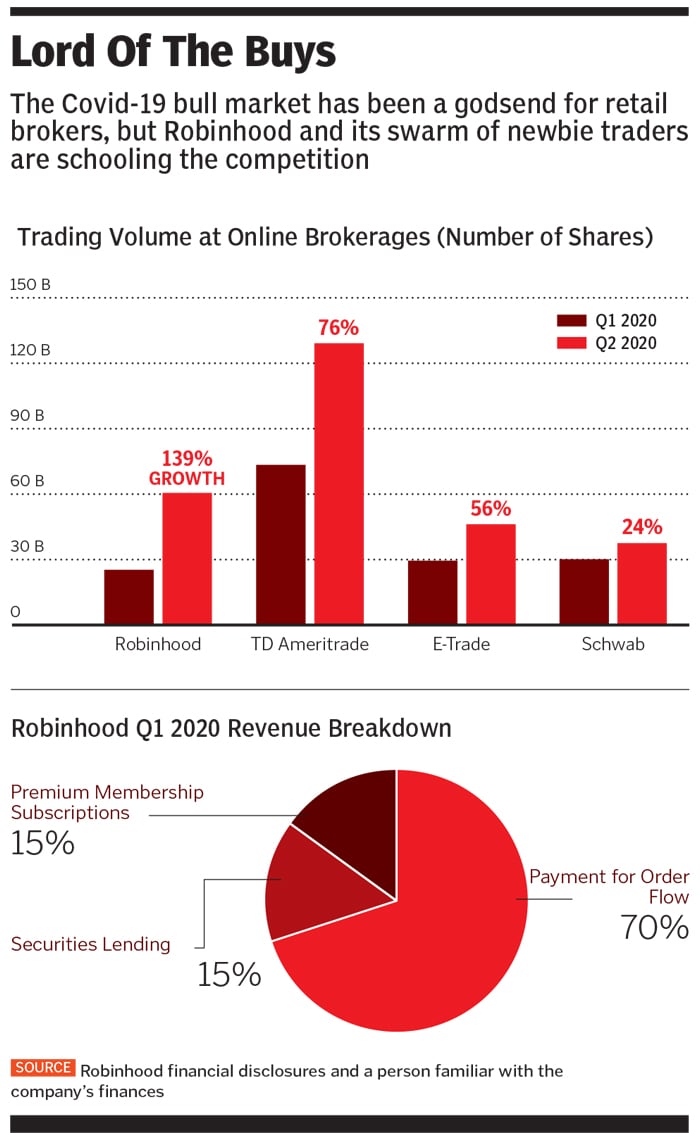

Covid-19 and the flow of government handouts have been manna from heaven for Robinhood. The firm has added more than 3 million accounts since January, a 30 percent rise, and it expects revenue to hit $700 million this year, a 250 percent spike from 2019, according to a person familiar with the private company’s finances. Not since May Day 1975, when the SEC deregulated brokerage commissions, giving rise to discount brokerages like Charles Schwab, has there been a more disruptive force in the retail stock market. Robinhood’s commission-free trading is now standard at firms including TD Ameritrade, Fidelity, Schwab, Vanguard and Merrill Lynch.

And Robinhood’s merry traders are moving markets: Certain stocks—Elon Musk’s Tesla, marijuana conglomerate Cronos, casino operator Penn National Gaming and even bankrupt car-rental company Hertz—have become favourites, swinging wildly on a daily basis. For the first time ever, according to Goldman Sachs, options speculators like the ones Robinhood has cultivated have caused single-stock option-trading volumes to eclipse common-stock trading volumes, surging an unprecedented 129 percent this year.

The Physics of Amateur Trading: Baiju Bhatt (left) and Vladimir Tenev met as physics students at Stanford University. Even the best modeling could not have predicted that $1,200 stimulus cheques would propel them to billionaire status

The Physics of Amateur Trading: Baiju Bhatt (left) and Vladimir Tenev met as physics students at Stanford University. Even the best modeling could not have predicted that $1,200 stimulus cheques would propel them to billionaire status“I think you’ve seen a unique situation in the history of financial markets,” says Tenev, working remotely from his home not far from Robinhood’s Menlo Park, California, headquarters, which resemble a beach house. “Typically when a market crash is followed by a recession, retail investors pull out. Institutions benefit. . . . In this case, Robinhood customers started opening new accounts and existing customers started putting in new money. This bodes positively for society and our economy if millions are investing when they otherwise wouldn’t have.”

Like any skilled trader, Tenev is talking his book. His proclamations ring a bit hollow, though, once you look more closely at what is actually driving his digital casino. From its inception, Robinhood was designed to profit by selling its customers’ trading data to the very sharks on Wall Street who have spent decades—and made billions—outmaneuvering investors. In fact, an analysis reveals that the more risk Robinhood’s customers take in their hyperactive trading accounts, the more the Silicon Valley startup profits from the whales it sells their data to. And while Robinhood’s successful recruitment of inexperienced young traders may have inadvertently minted a few new millionaires riding the debt-fueled bull market, it is also deluding an entire generation into believing that trading options successfully is as easy as leveling up on a video game.

Stock options are contracts to buy or sell underlying shares of stocks for a set price over a specified period of time, typically at a fraction of the cost. Given their complexity, options trading has long been the realm of the most sophisticated hedge funds. In 1973, three PhDs—Fisher Black, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton—developed an options pricing model that eventually won them the Nobel Prize in economics. Today their mathematical model, and variations of it, are easily incorporated in trading software so that setting up complicated—and risky—trades is no more than a few clicks away. Even so, making wrong bets is easy. According to the Options Clearing Corporation, more than 20 percent of all options trades expire worthless versus 6 percent “in the money.”

In June, Robinhood witnessed firsthand what can happen when such tools are marketed to inexperienced investors. While it’s impossible to discern every factor contributing to suicide, one of Robinhood’s new customers, a 20-year-old college student from Illinois named Alexander Kearns, took his own life after mistakenly thinking that one of his options trades put him in debt to Robinhood for more than $730,000. His death prompted questions from several members of Congress about the platform’s safety.

Despite these problems, millions continue to flock to the addictive app, and Tenev and Bhatt sit on a potential gold mine reminiscent of Facebook in its pre-IPO days. Amid its Covid-19 business surge, Robinhood has raised $800 million from venture investors, ultimately giving it a staggering $11.2 billion valuation, affording its co-founders a paper net worth of $1 billion each. But in light of Morgan Stanley’s success with its $13 billion acquisition of E-Trade in February and Schwab’s earlier purchase of TD Ameritrade for $26 billion, some think Robinhood could garner a $20 billion valuation if it went public or were acquired.

The problem is that Robinhood has sold the world a story of helping the little guy that is the opposite of its actual business model: Selling the little guy to rich market operators with very sharp elbows.

*****

The rise of Vladimir Tenev and Baiju Bhatt is a familiar one in the era of technology disruption.

They met as undergrads at Stanford University in the summer of 2005. “We had some astounding parallels in our lives,” says Bhatt. “We were both only children, we had both grown up in Virginia, we were both studying physics at Stanford, and we were both children of immigrants because our parents were studying PhDs.” Tenev’s family emigrated from Bulgaria, Bhatt’s from India.

Tenev, the son of two World Bank staffers, enrolled in UCLA’s math PhD programme but dropped out in 2011 to join Bhatt and build software for high-frequency traders. That was shortly after Wall Street’s 2010 ‘Flash Crash’, a sudden, near-1,000-point plunge in the Dow Jones Industrial Average at the hands of high-speed traders. The extreme volatility exposed how financial markets had mostly moved away from the staid, but stable, New York Stock Exchange and to a smattering of opaque quantitative trading pools dominated by a handful of secretive firms. These so-called ‘Flash Boys’, who worked milliseconds ahead of orders from both retail and institutional investors, had emerged from lower Manhattan’s back offices and IT departments, as well as university PhD programmes, to become the new kings of Wall Street.

At the same time Tenev and Bhatt were getting an insider’s education in how high-frequency traders operate and profit, the outside world was in turmoil, recovering slowly from the battering of the 2008-2009 financial crisis. It all played into the official Robinhood creation story: When the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement materialised as a protest of bailouts on Wall Street and foreclosures on Main Street, one of Tenev and Bhatt’s friends accused them of profiteering from an unequal system. Soul searching led the pair in 2012 to conceive Robinhood, a trading app with a name that was an explicit reference to leveling the playing field. The most obvious—and disruptive—innovation: No commissions and no minimum balances, at a time when even low-cost rivals like E-Trade and TD Ameritrade made billions on such fees.

Initially, Tenev and Bhatt used the allure of exclusivity to capture interest. For their 2013 launch, they restricted access, building up a 50,000-person waiting list. Then they turned the velvet rope into a game, telling prospective users they could move up the waitlist by referring friends. By the time they launched on Apple’s App Store in 2014, Robinhood had a waitlist of 1 million users. They had spent virtually nothing on marketing.

Bhatt focussed maniacally on app design, trying to make Robinhood “dead simple” to use. iPhones flashed with animations and vibrated when users bought stocks. Every time Bhatt came up with a new feature, he’d run across the street with staffers from Robinhood’s Palo Alto office to Stanford’s campus, cornering random students, asking for feedback. The app won an Apple Design award in 2015, a prize given to just 12 apps that year. Millennial customers started downloading it in droves.

By the fall of 2019, Robinhood had raised nearly $1 billion in funding and swelled to a $7.6 billion valuation, with 500 employees and 6 million users. Tenev and Bhatt, both minority owners of Robinhood with estimated 10 percent-plus stakes, were rich.

Then, in September 2019, Goliath bowed low to David. Over a 48-hour span, E-Trade, Schwab and TD Ameritrade, industry giants many times Robinhood’s size, cut commissions to $0. A few months later, Merrill Lynch and Wells Fargo’s brokerage unit followed suit. As this source of revenue evaporated, brokerage stocks plunged, and TD Ameritrade soon entered a shotgun marriage with Schwab, while E-Trade ran into the arms of Morgan Stanley.

Two Millennials had done something that discount giants like Vanguard and Fidelity never could. They had dealt the final blow to the easy-money trading commissions that had fed generations of stockbrokers and formed the financial foundation of Wall Street brokerage firms.

*****

The secret sauce of Robinhood’s success is something its founders are loath to publicise: From the beginning, it staked its profitability on something known as “payment for order flow”, or PFOF.

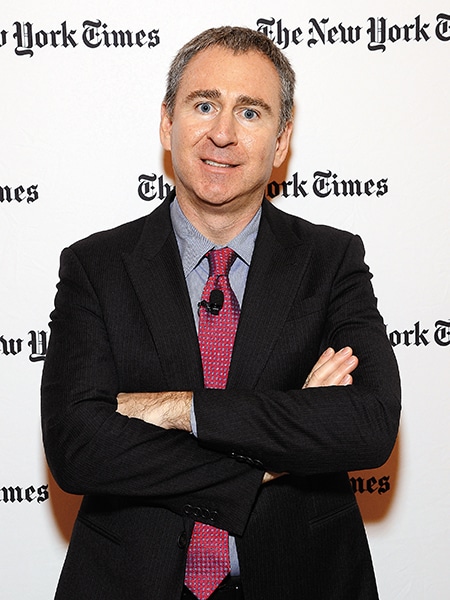

Instead of taking fees on the front end in the form of commissions, Tenev and Bhatt would make money behind the scenes, selling their trades to so-called market makers—large, sophisticated quantitative-trading firms like Citadel, Two Sigma, Susquehanna International Group and Virtu Financial. The big firms would feed Robinhood customer orders into their algorithms and seek to profit executing the trades by shaving small fractions off bid and offer prices.

Robinhood didn’t invent this selling of orders—E-Trade, for example, earned about $200 million in 2019 through the practice. Unlike most of its competitors, though, Robinhood charges the quants a percentage of the spread on each trade it sells, versus a fixed amount. So when there is a large gap between the bid and asked price, everyone wins—except the customer. Moreover, since Robinhood’s customers tend to trade small quantities of stocks, they are less likely to move markets and are thus lower-risk for the big quants running their models. In the first quarter of 2020, 70 percent of the firm’s $130 million in revenue was derived from selling its order flow. In the second quarter, Robinhood’s PFOF doubled to $180 million.

Given Tenev and Bhatt’s history in the high-frequency trading business, it’s no surprise that they cleverly built their firm around attracting the type of account that would be most desirable to their Wall Street trading-firm clients. What kind of traders make the most saleable chum for giant sharks? Those who chase volatile momentum stocks, caring little about the size of spreads, and those who speculate with options. So Robinhood’s app was designed to appeal to the video-game generation of young, inexperienced investors.

Besides being given one share of a low-priced stock to start you on your investing journey, one of the first things you notice when you begin trading stocks on Robinhood and are authourised to trade options is that the bright orange button right above BUY on your phone screen says TRADE OPTIONS.

Billionaires in Sherwood Forest: No one loves Robinhood trades more than Wall Street’s billionaire quants. Citadel, owned by Ken Griffin (above), No 34 on The Forbes 400, is the biggest buyer

Billionaires in Sherwood Forest: No one loves Robinhood trades more than Wall Street’s billionaire quants. Citadel, owned by Ken Griffin (above), No 34 on The Forbes 400, is the biggest buyerImage: Larry Bu Sacca / Getty images for New York Times

Options trades also happen to be prime steak for Robinhood’s real customers, the algorithmic quant traders. According to a recent report by Piper Sandler, Robinhood gets paid—by the quants—58 cents per 100 shares for options contracts versus only 17 cents per 100 for equities. Options are less liquid than stocks and tend to trade at higher spreads. Selling options trades accounted for 62 percent of Robinhood’s order-flow revenues in the first half of 2020.

The most delectable of these options trades, according to Paul Rowady of Alphacution, may very well be so-called “Stop Loss Limit Orders”, which give buyers the opportunity to set automatic price triggers that close their positions in an effort either to protect profits or limit losses. In October 2019, Robinhood gleefully announced to its customers, “Options Stop Limit Orders Are Here”, a nifty feature that essentially puts trading on autopilot.

“That [stop limit] order is immediately sold to a high-speed trader who now knows where your intention is, where you would sell,” says one former high-speed trader. “It’s like you’re writing a secret on a piece of paper and handing it to your broker, who sells it to someone who has an interest to trade against you.”

Robinhood refutes the notion that its model preys on inexperienced investors. “Receipt of payment for order flow is a common, legal and regulated industry business practice,” says a Robinhood spokesperson who insists the firm’s trade executions saved customers $1 billion this year. “We are focussed on providing a platform that makes finance accessible and approachable and where people can make thoughtful, informed investing decisions.”

Billionaire competitor Thomas Peterffy, the founder of Interactive Brokers, says stop limit orders are the most valuable orders a sophisticated trader can buy. “If people send you orders, you see what they are. You can plot them up along a price axis and see how many buy and sell orders you have at each of those prices,” he says.

For instance, if a buyer sees sell orders bunched up around a certain price, it means that if the stock or option hits that price, the market is going to fall hard. “If you are a trader, it’s good for you if you can trigger the stop—you can go short and trigger the stop, and then cover much lower,” Peterffy says. “It’s an old technique.”

*****

In a sense, Covid-19 has been both a blessing and a curse for Robinhood.

The pandemic forced millions of future Robinhood customers home, free from diversions like sports and armed with fast internet connections and money from the government. The stock market, meanwhile, provided edge-of-your-seat excitement as it plunged and then soared, propelling superstars like Amazon and reviving walking-dead stocks like Chesapeake Energy. The result was unprecedented growth for the upstart brokerage. Robinhood now has more than 13 million registered customer accounts, nearly as many as venerable Charles Schwab, which after 49 years has 14 million funded accounts, and more than twice as many as E-Trade, with 6 million accounts.

The company has also been a game changer for some of its clients. Taylor Hamilton, 23, an IT worker who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 2018, opened a Robinhood account and began trading in March. He began buying put options against plummeting travel-industry stocks like Delta and Uber, and later bought calls on Boeing and other beaten-down companies, correctly figuring that they would benefit from the government’s de facto bailout via the bond market.

After four months and 300 trades, Hamilton has netted nearly $100,000 and paid down his $15,000 in student loans. “It felt like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” says Hamilton, who reports that he has transferred most of his profits to his bank account to eliminate the temptation to trade away his gains.

The pandemic has also exposed Robinhood’s warts. During the market’s 5 percent one-day swoon and subsequent rebound in early March, its customers were shut off from their accounts for nearly two days as the firm’s technology systems crumpled under the weight of a tenfold jump in order volume. Angry customers lashed out against Robinhood on social media, and more than a dozen lawsuits were filed against it.

In the last few months, Robinhood has quietly been restructuring. Tenev says it’s making major technology investments to increase capacity and add redundancy. A sizable chunk of its $800 million in fresh venture capital is going toward upgrades and adding engineers to the 300 already on staff.

In the wake of the Kearns tragedy, Robinhood’s options-trading interface is being overhauled. The company has pledged to help educate its customers on the speculative nature of the trades. That includes hiring an ‘Options Education Specialist’ and “rolling out improvements to in-app messages and emails” that it sends to customers about their options trades. In August, the brokerage app said it would hire hundreds of new customer-service representatives in its Texas and Arizona offices by the end of 2020.

According to insiders, there’s a sense of urgency at the company these days. For two years, Robinhood has been speaking publicly about an IPO. With interest rates near zero and the stock market roaring, the public-offering window is wide open, but it won’t be forever.

A better option—especially considering Robinhood’s current problems—might be a quick sale to a full-service firm such as Goldman Sachs, UBS or Merrill Lynch. It would provide billion-dollar windfalls for its young founders, Tenev and Bhatt. And as any good trader knows, it’s much better to sell when you can than when you have to.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)