Sticker Apps Spell Big Money In Asia. Now In The West Too?

Young Asians spend millions on cute images they obsessively text one another. Entrepreneurs are betting the craze won't get lost in translation to the West

Franky Aguilar was tired of drawing family-friendly cartoons. The young designer was pulling down $90,000 a year at gaming giant Zynga when, in early 2012, he started hanging out at a Starbucks in Walnut Creek, California, with his cracked MacBook and a $100 Wacom tablet. He began scribbling fire-spewing cat heads and flying squadrons of fuchsia donuts, odder visions that harkened back to his high school graffiti days.

Aguilar, who had taught himself programing, cobbled his drawings into a photo editing app called Catwang and released it for free in April 2012. A month later the app had more than 130,000 downloads by people pasting his cartoons on photos they would share on Instagram. Within two months the app was bringing in $400 a day. In two years Catwang alone has sold $250,000 worth of stickers. “It was more money than I’d ever seen in my life,” says Aguilar, who quit the Zynga job a few months after Catwang hit the market.

Soon after, Aguilar and street-apparel maker Upper Playground sold rapper Snoop Dogg on an app called Snoopify, which offers $1.99 packs of cartoon pimp hats and dreadlocks. On a whim he made a $99.99 marijuana joint called the Golden Jay. Incredibly, 1,000 people have bought it to garnish their Instagram selfies.

This desire to spend $100 on a digital spliff is the same basic human craving Aguilar saw at Zynga, which has a thriving virtual goods business in tricked-out FarmVille tractors. At Zynga they called it “invest and express”. Stickers and smaller emoji symbols are a way to cope with the never-ending teen angst over being liked and are accelerating a broader social trend away from communicating with text. Bertrand Schmitt, the 37-year-old founder of app analytics firm App Annie, says that when his Beijing staff text each other after hours on WeChat “there will be seven or eight messages without anyone having said anything [with words]. People are moving towards a more graphical version of communicating.”

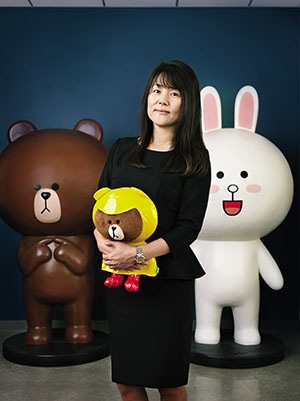

A crowd of artists, brokers and publishers are building a market for digital stickers that may be way bigger than the one for the tiny emojis that now dress up chats and Instagram. There are already 600 sticker apps in the iTunes and Play stores, but most of the action is on messaging apps such as LINE, backed by South Korean search giant Naver. LINE has 420 million registered users worldwide, who send 1.8 billion stickers each day picked from a vault of 10,000 that LINE produces in-house. Some, like the troubled bear-and-rabbit romance of Brown and Cony, have become so popular that they’ve spun off into books and TV shows.

Most people would never dream of paying for a fire-breathing cat. Nearly all sticker users on the messaging app Kik use its free stickers. Facebook doesn’t even bother charging—its Lego- and Minion-branded stickers are all gratis. Over in Asia, though, LINE does a brisk business. It sold nearly $70 million worth of stickers in 2013, or 20 percent of its $338 million in total revenue last year. Stickers could rake in another $140 million this year. That’s enough cash flow, says sticker broker Evan Wray, to make a $2 billion market by the end of this year, as the trend migrates westward and users of messaging apps like LINE and WeChat double to 2 billion by the end of 2014, according to Wray’s estimates.

The bullish estimates assume that stickers will be that rare Asian pop culture phenomenon that breaks through the translation barrier in the West. Jeanie Han, LINE’s US chief, has already seen this happen in Spain, where more than 10 million people have reportedly downloaded it. Han was setting up sticker-creature content deals in Spain before she even moved to America. The Spanish, she says, are fast at adopting new technology. It’s also a cheap thrill in an emotionally expressive country with 54 percent youth unemployment.

South Korean messaging app KakaoTalk got a single-digit proportion of its $200 million in 2013 revenue from digital stickers. That percentage would be higher, says KakaoTalk’s CEO, Sirgoo Lee, if payment for stickers was easier on Android, on which Google Wallet and carrier billing still trail Apple with its 800 million iTunes account holders. Wray, 24, says 75 percent of his sticker sales happen on iPhones, where it’s easier to make in-app payments. Another challenge: WhatsApp and Instagram, two of Facebook’s biggest mobile services, look unlikely to accommodate sticker-like graphics this year, say people close to the companies.

To break into the US, sticker tycoons are targeting familiar brands. Wray, the sticker broker behind TextPride, has produced stickers for British soccer clubs like Tottenham Hotspur and movies like Kill Bill for Miramax Films, and sells them on to messaging apps, taking a double-digit cut of revenue. He has partnerships with half a dozen recognisable media and messaging names in the pipeline.

Some US startups will continue to pursue Asian-style whimsy. Former rock musician Bobby Schubenski and partner Jim Somers started goth-skater clothing company Blackcraft Cult. In April they started selling a $1.99 Black Craft sticker pack with variations of their trademark Lucipurr the cat, skulls, beer glasses and emojis, such as a middle finger. They think stickers could help double last year’s sales of $1.3 million, mostly in apparel. “Everybody needs a middle-finger emoji,” Schubenski says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)