Revenge of the record labels

While Jay Z's streaming service grabs headlines, music's majors are quietly hijacking the multibillion-dollar digital revolution

Last October, SoundCloud—a free music-streaming service with a massive 175 million monthly users—appeared to be running out of cash. News broke that the Berlin-based company had lost $29.2 million in 2013, and when a rumored $2 billion buyout bid by Twitter fell through, it looked like music’s hottest startup might be in danger of going bust.

Yet, despite the credibility they bestowed on each other, Warner and SoundCloud have largely eschewed talking about the partnership—neither side would comment to Forbes—and have zealously guarded the terms. Why? A source with knowledge of the agreement says the record company acquired its SoundCloud stake at a discount of about 50 percent from what other investors paid. And such details illustrate a quiet revolution in the digitisation of the music industry that all sides seem to prefer go unnoticed.

Left for dead by most investors and pundits, the surviving Big Three labels—Warner, Universal and Sony—have quietly muscled out stakes of the hottest digital entertainment startups, including 10-20 percent, collectively, of the established streaming services, such as Spotify and Rdio. Terms are similarly stark for younger startups: The labels take stakes for free or on the cheap, and then often give themselves the right to buy larger chunks at deep discounts to market later on. It’s not just streaming: The labels have gobbled up pieces of startups ranging from choose-your-own-adventure music video purveyor Interlude to song-recognition giant Shazam—valued at $1 billion in its latest round—which counts Carlos Slim, the second-richest man in the world, among its investors.

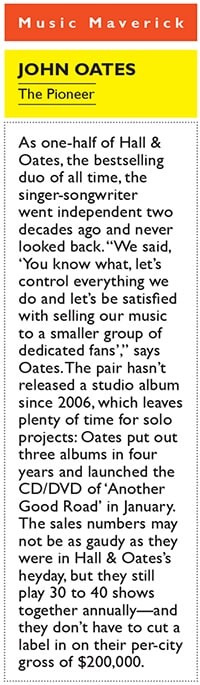

And what have the labels been giving the startups, aside from legitimacy, to secure these sweetheart deals? All-encompassing access to the artists and their songs—a neat little trick. Sure, the artists derive some minimal amount of royalties from these new channels, but they aren’t getting any of the ownership. “That’s the story of the music business,” says John Oates, one-half of Rock and Roll Hall of Fame duo Hall & Oates, who went independent almost 20 years ago amid frustration over their financial arrangements with labels. “It goes back to the earliest days—take it back to, ‘Give him a bottle of wine and take all his publishing for the rest of his life’.”

The artists are starting to fight back—and not just by opting out of the system. Earlier this year, Jay Z purchased Swedish high-resolution-streaming services WiMP and Tidal for $56 million, merging them into a single service to compete directly with Spotify. At the official launch, 16 of music’s biggest acts were introduced as the new “owners” of Tidal, including Beyoncé, Calvin Harris, Kanye West, Alicia Keys, Jason Aldean and Daft Punk. Each was reportedly offered a 3 percent stake.

Representatives from all three major labels—as well as Beats, Spotify and Rdio—declined or did not respond to requests for a comment on whether or not the majors demanded free or cheap equity in streaming companies as part of the price of doing business. But in industry circles, the practice is an open secret.

Forbes estimates that the three labels have amassed positions in digital music startups valued at almost $3 billion—or around 20 percent of the $15 billion or so the labels are collectively worth. The percentage will shoot even higher if and when Spotify goes public. And some bets have already paid off: Universal Music Group took an early position in Beats by Dr Dre and owned 13 percent when Apple bought the company for $3 billion last year, resulting in a $404 million score. Artists + leverage = digital windfall. That’s the kind of math, applied across all their revenue models, that the labels hope puts them back atop the musical food chain.

To understand the urgency the labels feel, it’s helpful to walk through what they’ve endured. Total US album sales peaked at 785 million in 2000—the year after a pair of teenagers named Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker created Napster, which allowed anyone with a computer and a reasonably fast web connection to trade music.

By 2008, annual album sales had plummeted 45 percent. Between then and now, even as the labels reined in illegal downloading, sales dropped another 40 percent to 257 million. That means, at $15 per album, the industry is currently taking in $7.9 billion less in annual retail sales than it was a decade-and-a-half ago. Initially, the labels’ response was to fight piracy in court and to fold into one another. There were six majors in 1999; now there are three.

So far, two dominant streaming models have emerged: Internet radio companies like Pandora that allow subscribers to passively listen to music that’s customised for their tastes and interactive ones like Spotify that allow users to pick songs.

The former can operate under a government-mandated licence that dictates how much they have to pay. By contrast, Spotify and others must strike deals with labels and publishers in order to license music for legal use in the US.

One insider says YouTube alone paid the majors more than $1 billion in advances over the past two years. Spotify pays out about 70 percent of its revenue—at a rate of 0.7 cents a spin—to labels and publishers, who then pass along a small fraction to their artists and songwriters.

These arrangements offer labels another way to leverage their artists to make money from digital streaming: Arbitrage. The formula for how much Pandora, YouTube and Spotify pay the labels isn’t related to the formula that the labels use to pay the artists whose songs are played. The latter is determined by a combination of individual contracts and a structure so byzantine that it goes by a moniker only a secretive hedge fund quant could love: The ‘black box’.

So how do the labels make money from the spread? Let’s understand the concept of ‘breakage’. The labels generally ask for digital partners to front an advance, not unlike how they worked with the record clubs of yesteryear. When a contract expires, there’s often a difference between the royalties earned and the initial advance. The labels generally keep that difference. When the labels re- negotiate, it’s with entities in which they hold significant stakes, ensuring the same rules apply all over again.

The black box has many other ways to squeeze money from the artist. For example, ‘Drunk in Love’ is undoubtedly a hit single performed by Beyoncé and Jay Z—but it exists under many different names (‘Drunk in Love’ by Various Artists, by Beyoncé featuring Jay Z, etc). In cases of mislabelling, royalties don’t typically go to music’s royal couple but rather a pool of unclaimed cash eventually doled out to the labels at a rate commensurate with their market share. And while US laws exempt broadcasters from paying out royalties on the recording side, foreign laws often do not. When an American act scores a hit in the UK, it’s not clear how often the UK label pays through to the US label and performer. Forbes estimates that labels are collecting $300 million worth of putatively “unattributable” money each year.

“By not having great data and not having a worldwide database,” says John Simson, who used to run SoundExchange, a non-profit trade association responsible for collecting artist and label royalties on digital transmissions, “it just makes it easier for money to go to the black box.”

Labels have also increasingly used their leverage to get a piece of concert revenue. This is relatively new: Historically, touring was often a loss leader to boost album sales. Now that it’s reversed—most of the profit in the music industry comes from live shows—the majors take a piece of the profit in exchange for their promotion and marketing for the acts overall. These so-called 360 deals date back to the days of the Monkees and became prevalent when Live Nation started shelling out nine-figure advances to the likes of Jay Z and Madonna (both now stakeholders in Tidal) for such arrangements about a decade ago.

These days, 360 deals are mostly reserved for young acts with little leverage; under such an agreement they typically give up 10-20 percent of what they net on shows to the label. Of course, these sorts of heavy-handed tactics have existed since the early days of the phonograph. Thomas Edison himself founded Edison Records—and refused to even print artists’ names on his products, let alone pay transparent rates.

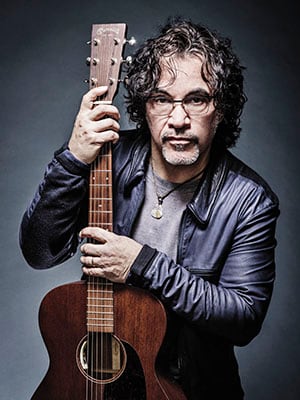

Alternative rocker Amanda Palmer took to crowdfunding to finance her last studio album—she raised a record $1.2 million on Kickstarter in 2012. “I’ll probably make enough money on Spotify to buy me a sandwich,” she says. “[But] I don’t think you can put this genie back in this particular bottle. I think you’re better of trying to cope with the reality instead of pretending that the reality doesn’t exist.”

Even by coming up with new takes on old tricks and accumulating pieces of popular streaming services, the majors still have a rough road ahead: Universal and Warner recently reported quarterly revenues that were flat or down on a year-over-year, constant-currency basis. Sony Music’s revenues were up by 13 percent thanks to releases by Garth Brooks, One Direction and Pink Floyd—and the favourable depreciation of the yen against the dollar. In some cases, their startup stakes are held by the label’s parent companies, so positive results wouldn’t necessarily show up on the same balance sheet—but for the most part, streaming services aren’t yet in the black anyway. That may change as usage scales up. According to MusicWatch’s Russ Crupnick, in 2013 only 45 percent of the 190 million internet users in the US bought music in any form, spending an average $55.45 per year. A full year of premium service on Spotify or Rdio (or Tidal) costs $120.

“It’s a mathematical case,” says Robb McDaniels, founder and former CEO of INgrooves, which handles digital distribution for Universal Music Group (and is now partly owned by it). “If everyone signed up, the pot would be many times as big. So that’s actually good for artists. The key is, we have to get the average music consumer to sign up instead of just the early adopters.”

Spotify is making steady progress—as of January 2015, it had 60 million active users, 15 million of whom were paying for the premium version; both these numbers are up by about 150 percent from March 2013. And the company doesn’t need to be profitable to go public: In the event that it does, the labels will likely share a windfall in excess of $1 billion. The per-spin payouts may continue to grow, but there will be no pro rata share of an IPO jackpot going back to the artists and songwriters who made the music responsible for the company’s rise.

Though, tellingly, none of the majors was willing to comment for this story, their executives have been transparent enough about their intentions. In a memo laying out goals for his company in 2015, Universal chief Grainge expressed a desire for the company to “be a formative player in shaping and developing the music platforms of tomorrow”. By looking forward, while squeezing the models of the past, the record label seems to be on its way to avoiding extinction.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)