Reed Hastings rewrites the Hollywood script

Netflix had already upended Hollywood when the pandemic hit. But by making use of a highly unusual management style, its billionaire founder has positioned his juggernaut to prosper like few companies in the world right now

Reed Hastings

Reed HastingsImage: Kwaku Alston for Forbes

The man responsible for keeping the world entertained does so, at least this day, alone in front of a computer screen, in his son’s largely unadorned childhood bedroom. In some ways, it’s the perfect setting for Reed Hastings, the unpretentious co-founder and co-CEO of Netflix, whose global army of innovators has revolutionised entertainment in the home. While Hollywood measures people’s offices by their totems and grandeur, the analytical Hastings, a Silicon Valley interloper, values functionality over trappings.

Netflix currently functions, by any measure, at a world-class level. As the year of the pandemic upends entertainment companies—Disney’s crippled theme parks, Warner Bros’ furloughed blockbusters, AMC’s shuttered theaters—Netflix is having a moment. A moment of prestige, with a record 160 Emmy Award nominations, eclipsing the long-dominant HBO, and more Oscar nods than any other media company. A moment of influence, adding almost as many customers in the first six months of the year as in all of 2019, extending its reach to nearly 200 million subscribers in 190 countries. And a moment of profits, with sales up 25 percent year over year, earnings more than doubled and its stock up 50 percent, as most of the market gyrates wildly just to scratch back to even. Recent market cap: $213.3 billion.

All these data points stem from data points, and a perfect synthesis of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, serving up content informed by a deep understanding of their users’ tastes. “We fundamentally want to be better at creating stories people want to talk about and watch than any of our competitors,” says Hastings.

Those competitors have gotten the memo, spending billions to confront Netflix, whether via Disney’s fast-growing Disney+, WarnerMedia’s lurching HBO Max or NBCUniversal’s brand-new Peacock. Says Hastings with a shrug: “What people forget is, it’s always been intense competition. I mean, Amazon did streaming at the same time we did in 2007. So we’ve been competing with Amazon for 13 years.”

Fair enough. But for Amazon, streaming has almost surely been a loss leader that can generate Prime shopping memberships. For Jeff Bezos, entertainment will always be a side hustle. The Hollywood establishment, meanwhile, can leverage its content libraries and know-how all it wants, but what makes Netflix tick is something nearly impossible for companies built on ego and image to replicate: A culture of Vulcan-like dispassion and transparency, combined with perpetual, rapid reinvention.

All this has come to a head amid the most disruptive moment for entertainment in at least a generation. In some ways, Hastings, who clocks in at number 132 on The Forbes 400 with a net worth of $5 billion, has been preparing for this moment for the past two decades. What the 59-year-old does right now, and how he leverages this culture—an unusual one even by tech-industry standards—will determine what you will watch, laugh along with and cry over for the next two decades.

*****

If Hastings seems unnaturally comfortable amid the train wreck that is 2020, perhaps it’s because his company’s culture was forged in crisis. A nascent business in 2001, Netflix saw its funding dry up in the aftermath of the original dot-com bust. Then came 9/11. As the end of that terrible year approached, Hastings needed to cut one-third of his employees.

To do so, he and Patty McCord, Netflix’s chief talent officer, diligently tried to identify the highest performers, terming them the “keepers”. As the day of the painful bloodletting drew near, he was on edge, worried that morale would plummet, with those who remained growing bitter under the increased workload.

The opposite occurred. With the merely competent employees cleared out, the office was energised, “buzzing with passion, energy and ideas”. Hastings describes the painful layoffs as his “road to Damascus experience,” a clarifying moment that changed his understanding of employee motivation and leadership. It would lay the foundation for what might be called the Netflix Way, the web-era successor to the HP Way, Bill Hewlett and David Packard’s pioneering management approach that created one of Silicon Valley’s earliest garage-to-greatness stories.

The Netflix Way starts with building a roster of elite talent. In Hastings’ new book, No Rules Rules, he likens his company’s culture to that of a championship professional sports team—one that works and pulls for one another, but sheds no tears when a teammate is jettisoned in favour of an upgrade. Perennial trophies require perpetual hiring of top performers.

So what does this really mean in terms of how Netflix operates? First, it pays top dollar to secure the right talent. That practice began in 2003, when Netflix began competing with Google, Apple and, soon, Facebook for the “rock stars” whose highly refined coding, debugging and programming skills dramatically outperformed their average peers. It extended this generous compensation to creative executives working in Hollywood, from the well-connected (Matt Thunell, whose ties with the talent community enabled him to read an early draft of the sci-fi series Stranger Things over lunch in Hollywood) to the visionaries (Shonda Rhimes, Joel and Ethan Coen, Martin Scorsese). Those large cheques singlehandedly turned streaming from a backwater to an auteur’s paradise, with early hits like House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black. The eyeballs followed.

“In the beginning we were able to attract rebellious folks, the folks that were stifled by the studio environment or hadn’t gone far enough in the system to be ruined,” McCord says. “We just wrote big cheques. ‘I know it seems crazy. I know you don’t get a personal assistant. You don’t get a parking spot. How about we give you this big shitpile of money?’”

Those piles are delivered cleanly. The company’s pay packages come fully as salary, with as much or as little compensation as you wish in stock options; Netflix doesn’t believe in bonuses, which Hastings thinks can reward the wrong things. “It’s the specifics of trying to hold someone accountable that trips you up,” he says “We do evaluate people, but we don’t micromanage the goals.”

A corollary, though: These stars, all paid like stars, must continue to perform like stars. No part of the company tolerates resting on one’s laurels. “Adequate performance gets a generous severance package,” Hastings and McCord wrote in a 129-page SlideShare presentation on Netflix’s culture that was widely shared a decade ago and remains on the company’s website.

“We describe it as like getting cut from an Olympic team. And it’s super-disappointing. You’ve trained your whole life for it, and you get cut, and it’s heartbreaking,” Hastings says. “But there’s no shame in it at all. You have the guts to try.”

Extending the sports analogy, this team of elite players, in trusting one another’s exceptional skills, will then communicate openly to collectively up their game. It’s akin in some ways to Ray Dalio’s much-promoted “Principles” of brutal transparency at Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund. And it’s not for everyone. One former executive describes the work environment as a “culture of fear” in which “everybody is chipping away at each other at every moment—because you’re rewarded”. The annual review process, called “360”, culminates in dinners at which small groups gather to provide constructive feedback.

“Each one gives feedback about that person, live, in front of everybody else,” says the former executive, who requested anonymity. “You go around the table. It lasts for hours. People cry. Then you have to say ‘Thank you, because it’s making me a better person.’”

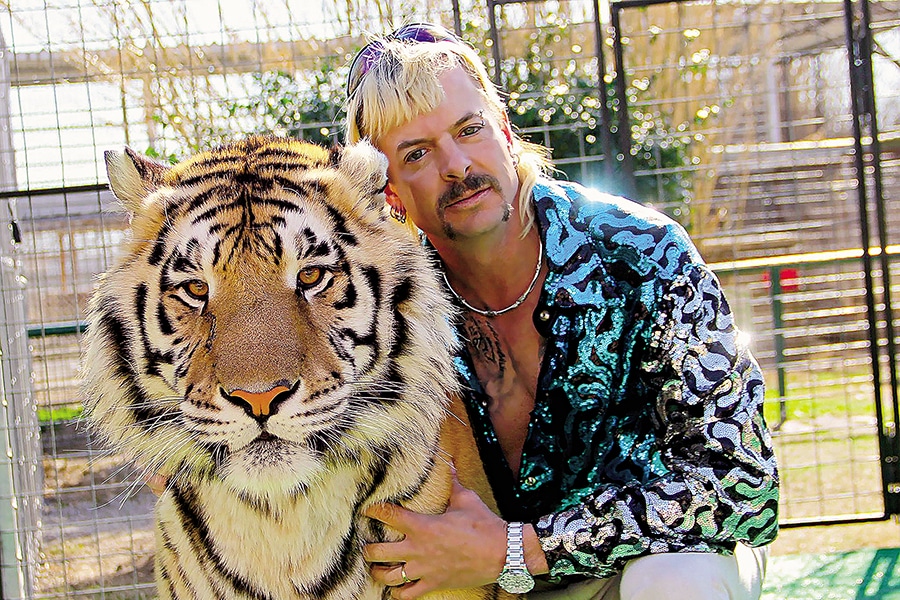

The Netflix mega-hit Tiger King stars Joe Exotic, a self-described “gay cowboy” big-cat breeder. The seven-part documentary captivated millions homebound by the pandemic

The Netflix mega-hit Tiger King stars Joe Exotic, a self-described “gay cowboy” big-cat breeder. The seven-part documentary captivated millions homebound by the pandemicTo Hastings, these 360 reviews are a necessary component because of another element of the Netflix Way: a huge amount of autonomy. Like the coach who wins championships by empowering stars to execute the game plan rather than trying to control each play, Hastings encourages the freedom to act in the company’s best interest.

Again, this can be disconcerting. Ted Sarandos, Hastings’ co-CEO, talks about a coffee break with Hastings in the pre-streaming days, when he was the chief content officer and deciding whether to order 60 copies of a new alien movie or 600. Sarandos casually asked Hastings how many he should order, and Hastings responded, “Oh, I don’t think that’s going to be popular. Just a few.”

Within a month, the movie was in high demand, and Netflix was out of stock. Hastings asked Sarandos why he hadn’t ordered more DVDs. “Because you told me not to!” Sarandos protested. Hastings cut the conversation off immediately, declaring: “You’re not allowed to let me drive us off the cliff!”

“And to me, that was an immediate lesson,” Sarandos now says. “With all that decision-making power comes responsibility. Reed models that over and over again, and he lets you own the win and he makes you own the loss.”

“Normally companies organise around efficiency and error reduction, but that leads to rigidity,” Hastings says. “We’re a creative company. It’s better to organise around flexibility and tolerate chaos.”

*****

Hastings has the kind of background that allows one not to fear failure. His maternal great-grandfather, Alfred Lee Loomis, was a Wall Street tycoon who anticipated the impending stock-market crash of 1929, then turned his attention to science, bankrolling luminaries such as Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi and Ernest Lawrence. Hastings grew up in an affluent suburb of Boston—his parents met while his father was at Harvard, his mother at Wellesley—and attended private schools, then Bowdoin College. He later obtained a master’s degree in computer science from Stanford and spent two years in the Peace Corps in Swaziland, teaching math to high school students.

In 1991, Hastings founded his first company, Pure Software, which specialised in programs for measuring software quality. Back then, he was a “geek’s geek” who would sleep on the office floor after an exhausting coding session. “I’d come in in the morning and say, ‘Dude, if you’re going to sleep on the floor, in the morning go brush your teeth and look for blanket fuzz in your beard,’” recalls McCord, who was with him at Pure before helping him formalise the culture at Netflix.

McCord watched the entrepreneur mature as a leader. She remembers encountering Hastings in his office late one evening, fixing bugs in the glow of his computer rather than preparing remarks for a company meeting the following day. “Seriously, Reed, if you want them to follow—lead,” McCord remembers telling him. “And I slammed the door. The next day he did a speech, and got a standing ovation. I don’t think he knew he had it in him. He realised it was his job to inspire them, not to do the work.”

Pure Software went public in 1995, merged in 1996 with a little-known Massachusetts company, Atria Software, and was subsequently gobbled up by Rational Software in a deal that PitchBook valued at around $700 million. A tremendous success, but one that came with a strain on his marriage. Counseling helped the once conflict-avoidant Hastings open up—and eventually he would incorporate the value of candour as a foundation of Netflix’s culture. “People shy away from the truth, and the truth isn’t so bad,” he says.

By Silicon Valley standards, Pure Software had made a successful exit. But it left Hastings with lingering dissatisfaction. In the early days, it had innovated. As it matured, like pretty much every company, it developed policies to safeguard against mistakes, rather than taking smart risks. Pure ended up promoting people “who were great at colouring within the lines,” Hastings says, while the creative mavericks got frustrated and went to work elsewhere.

That was Hastings’ mindset when, according to popular legend, he had an epiphany after getting socked with a $40 late fee on Apollo 13 at Blockbuster. “What if there were no late fees?” he pondered, and voilà, the idea for Netflix emerged fully formed.

“It’s a good story,” says Netflix co-founder Marc Randolph, who worked with Hastings at Pure. “And in many ways, Netflix is about telling good stories.”

Netflix’s origin story is more complicated than the convenient narrative. It hatched over countless brainstorming sessions while Hastings and Randolph commuted over the Santa Cruz Mountains to Pure’s headquarters in Sunnyvale, California.

Launched in 1997, Netflix became known for red envelopes sent by mail, a pivot away from Blockbuster’s brick-and-mortar rental model. Initially, it made most of its money selling DVDs, Randolph says. That put the young startup on an eventual collision course with Amazon’s Bezos.

Instead, Netflix caught fire in 1999 with a subscription model—customers would rent up to three movies at a time without worrying about a specific return date or incurring late fees. A better mousetrap, albeit one that carried a huge burn—Hastings lured customers with month-long free trials. Randolph remembers flying with Hastings to Dallas to try to convince Blockbuster CEO John Antioco to buy Netflix for $50 million. The head of the $6 billion home-entertainment giant rejected the idea out of hand.

“What did we possibly have to offer that they couldn’t do more effectively themselves?” Hastings reflects.

After the 2001 reset, Netflix’s business began to stand on its own and grow, raising $82.5 million through its initial stock offering in 2002. It developed into a very good business, as subscribers would pick DVDs from Netflix’s comprehensive library.

Then, in 2007, broadband brought the opportunity for streaming. Keen to ensure that no one did to Netflix what he had done to Blockbuster, Hastings began plowing cash and engineering resources into what was essentially a freebie for existing DVD subscribers. It was a fateful moment. Netflix’s old-fashioned business allowed for pretty much infinite choice, albeit within the confines of inventory availability and delivery lags. Streaming offered instant gratification, but Netflix would not be able to match the breadth of content because of Hollywood’s television deals. For the first time, Hastings had to understand people’s tastes and offer them a compelling proposition.

“When someone sits in front of a TV to watch Netflix, we have a moment of truth—a couple of minutes, maybe as little as 30 seconds, [in which] we need to catch their attention with something interesting,” says former chief product officer Neil Hunt, who deployed his 2,000-member team to solve this riddle—most working independently, in keeping with the company’s culture.

Netflix also needed to find a way to charge for the on-demand service—especially after it began spending as heavily to license streaming content as it did to purchase DVDs.

The race to capitalise on streaming’s future set up what Hastings calls the biggest mistake in the company’s history: The decision in 2011 to hive off the company’s aging DVD business in a separate service called Qwikster. Critics trashed the idea, and Hastings himself became comedic fodder for Saturday Night Live, which parodied his YouTube video apologising for the misstep. The debacle cost Netflix millions of subscribers, and its stock dropped more than 75 percent.

Hastings tearfully apologised for damaging the company at a weekend management retreat months later. It turns out that dozens of managers had qualms about Qwikster—but had kept their misgivings to themselves. That prompted Hastings to institute a practice of actively seeking out dissent before launching any new initiative.

Even before the misstep, some studio executives scoffed at Netflix as a competitive threat. “It’s a little bit like, is the Albanian army going to take over the world?” Time Warner chief executive Jeff Bewkes said in a 2010 interview. “I don’t think so.”

“During all the critical years, 2010 to 2015, [Bewkes] just thought the internet was foolish, and the prices were foolishness,” Hastings says, noting that he still has the Albanian army dog tags he wore around his neck for motivation. “And so it caused him to ignore it until it was too late.”

By the time Hollywood started to get wise, Netflix had begun financing its own original series—starting with Sarandos’ $100 million bet in 2011 on the political thriller House of Cards, from director David Fincher. “What some people called overpaying for that content at that time, Netflix knew very well what it was worth and what they were building toward,’’ says Tinder CEO Jim Lanzone, a longtime internet entrepreneur who was CBS’ chief digital officer at the time.

“Changing course involves investment and risk that may reduce this year’s profit margin,” Hastings writes in No Rules Rules. “The stock price might go down with it. What executive would do that?” Unlike Hollywood executives, whose bonuses are pegged to delivering operational profits, Hastings ensures that his executives won’t be afraid of suffering a financial hit by taking a risk.

*****

The Covid-19 pandemic gave Netflix’s innovative culture a proper stress test. As film and television production ground to a halt in New York and Hollywood this spring, Netflix’s global content machine began sparking back to life. As at many white-collar companies, meetings resumed from living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens, virtual writers’ rooms were assembling and animators were working remotely. Remote autonomy wasn’t anything the Netflix crew needed to learn. And since Hastings has spent much of the past decade focusing internationally, content production resumed relatively quickly in Iceland and South Korea, which have been aggressive about testing and tracking.

Meanwhile, while rivals lost centerpiece launch shows, such as the Friends reunion special for HBO Max and the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, a tentpole for NBCUniversal’s Peacock, Netflix kept humming along with shows that captured the cultural zeitgeist, whether with crass obsessions like Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness, a goofy reality show based on the game Floor Is Lava or adrenaline-filled action flicks such as Chris Hemsworth’s Extraction.

Yes, those shows were lucky. But Netflix has volume and data to help create luck. “One thing that’s not widely understood is that we work really far out relative to the industry, because we launch all our shows, all episodes, at once,” Sarandos told investors in April. “And we’re working far out all over the world.”

The world has proven receptive. With movie theaters crippled, sports dormant until recently and traditional and cable television offering the equivalent of reheated leftovers, Netflix has added around 1 million subscriptions a month in the US and Canada since the pandemic began and another 2 million a month globally. The coronavirus, which has made so many developments accelerate, will inevitably prove to have ushered in the moment that streaming became the dominant platform for moving entertainment.

While Netflix dominates its space (it reaches 56 percent of US homes with broadband access, according to Parks Associates), Disney, in particular, is bringing the heat, with more than 100 million subscribers across its three services, Disney+, ESPN+ and Hulu. Disney chief Bob Iger went all in on its direct-to-consumer initiative, assembling its arsenal of powerful entertainment brands—Disney, Pixar Animation, Marvel Entertainment and Star Wars—to attract subscribers to Disney+, betting boldly like Netflix does, most notably deciding to use its $75 million investment in a filmed version of the hit Broadway musical Hamilton on its behalf.

Hastings acknowledges Disney’s extraordinary feat of logging 50 million subscribers in its first five months, a milestone it took Netflix seven years to reach. Meanwhile, he’s focussed on Netflix crossing its next significant milepost: 200 million subscribers and beyond. That means more investment in local content around the world—including as much as $400 million by the end of the year in India. And it means continuing to evaluate his talent so he can continue to empower them to make decisions.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)