One Woman, a hair dryer and a $20 million business

How Alli Webb turned her Drybar salon into a $20 million operation

It’s 11 am on a Tuesday in Drybar’s underground salon in the basement of Manhattan’s Le Parker Meridien hotel. With Adele belting it out over the sound system, rising above the roar of nine blow-dryers on full blast, women aged 21 to 62 are spun out sleek and smooth. One by one, the stylists spin their clients to face the mirror and show the results. “You look incredible,” says Drybar founder Alli Webb to a middle-aged attorney who admires herself.

“Great job,” Webb nods to the stylist, who, in turn, sighs to a co-worker, “God, she’s amazing.” What’s amazing is how Webb, a 37-year-old mother of two, has made a $20 million (sales) business out of nothing but hot air. Four years ago, she was peddling her services from a 2001 Nissan Xterra, driving around Los Angeles. “Between gas and babysitters, I doubt I ever broke even,” she recalls. Today, with 23 salons in six states (26 by year-end), Drybar is styling the hair of more than 50,000 women every month. At 40 bucks a pop—for just a blowout; no scissors, no dyes—it adds up. Drybar has the usual expenses of labour, real estate and utility bills. But each store nets 15 percent to 35 percent, says Michael Landau, who is CEO and Webb’s brother. Hair salons usually clear 11 percent or so.

The Drybar phenom may feel like a throwback to the weekly hairdo our moms (or grandmothers) used as a way to pamper themselves. But its success rests on a replicable formula that Webb, husband Cameron, Landau and architect friend Josh Heitler have laboured to perfect—down to every step along the 40-minute process of beautification, the decor and layout, even the soundtrack playlist. “I know what works, I know what doesn’t,” says Webb. “What we’re really selling is self-esteem.”

Brother Michael, 41, had doubts—especially after Alli came to him begging for $250,000 to open her first location in Brentwood, California. “Alli has always been overly confident that this was a service that women wanted, needed and would love,” says Landau, who served as a vice president of brand marketing at Yahoo before cofounding his own marketing company. “What does a guy with no hair understand about why a woman would need a blowout, much less why she couldn’t do it herself or would ever pay for it?”

The first few weeks turned his shiny head. In pro forma projections, he and Webb had figured it would take 20 to 30 blowouts a day to keep the doors open. But demand blew the doors off—even before they opened. After an e-mail blast went out, alerting Brentwood women about Drybar’s opening, thousands of appointments were in the books—six weeks’ worth in just eight hours by Landau’s count. He laughs in hindsight. Twenty to 30 blowouts “would be the single worst day we’ve ever had”.

Within weeks, they were overwhelmed, understaffed—and in danger of losing business. They’d planned on answering the phones at the receptionist desk like any other salon but wound up not being able to hear clients over the noise of the blow-dryers, resulting in dozens of missed appointments. Within weeks, they switched to a VoIP phone system and hired a receptionist to take calls in her living room and then communicate with the salon over instant message—a process still in place today, although the call centre now employs more than 50 customer service reps. Thanks to a classy, simple website designed by Alli’s husband, Cameron, you can book and pay for a blowout online.

Still, as Drybar began to scale up, new concerns surfaced. Three new stores opened in 2010—in West Hollywood, Studio City and Pacific Palisades—while Landau held his breath. He worried the new locations weren’t chic enough and that the concept wouldn’t translate. “I really thought the women of Brentwood just had too much time, too much money and cared too much about their appearances,” he says. “Turns out it’s universal.”

Rapid expansion strained the war chest. Since each new outlet cost $500,000, Drybar looked to franchising in late 2010, and quickly moved into seven new markets in California, Georgia, Texas and Arizona. They turned, for the most part, to longtime friends—even a pair of Landau’s fraternity brothers who head up Atlanta operations. But the model was shortlived. “It was a great growth vehicle for us, and we couldn’t ask for a better group of partners,” says Landau. “But, in the end, you can’t control consistency when they’re just not you.”

Consistency is all. Every Drybar looks roughly the same: A plate of cookies and a large pitcher of flavoured water at the front desk; soft, warm (read: flattering) lighting; furniture and design elements in white, buttercup and slate. Clients sit facing a U-shaped or single-stretch bar, with their backs to the mirrors since no woman wants to see herself until she’s properly done up. They can listen to music (the daylong tape of different tunes ensures that stylists won’t lose their minds) or watch chick flicks with subtitles. As for the “station”, where a woman gets worked on, “we don’t compromise on that and it never changes”, says Heitler, who has a 5 percent share of the business. “There’s a lot of embedded knowledge from the very first location about the choreography of our blowout.”

Ah, yes, the choreography. It begins with a consultation at the “bar”, where a stylist asks you which of five looks—all coyly named after girlie drinks—you want. Then you’re escorted to a quiet washroom in the rear where your hair gets washed and wrapped in a bun. Would you like a drink (water, coffee, champagne)? Any allergies to hair products?

Then to work, starting with the front, blow-drying into curls and pinning them to the top of your head, sectioning your hair and pulling it in front of your shoulders to make finishing touches in precisely the same way. Right before you’re done, out come the pins—“Are you ready?”—and you’re spun around. A little readjustment, followed by extra spray. “Doesn’t she look great/fabulous/so good?” your stylist addresses her peers.

All stylists—there are now 1,000—undergo a week of training at the hands of 10 master coiffeuses. That cadre endures a month of tough drilling with Webb, learning her techniques and sensibilities, as well as how to teach her method to new hires.

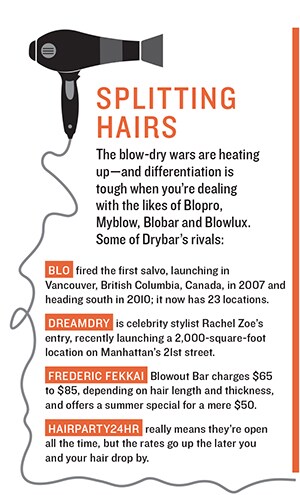

If “the Drybar way” is science, it’s hardly particle physics. The barrier to entry is so low that “we’re seeing new players come to the market in droves”, says Mintel market research analyst Amy Ziegler. “It’s about whether one or two players really emerge from the group.”

That’s where Drybar may have an edge. Aside from being first, Webb has been fast. Same-store sales will jump 30 percent this year over last. While not all stores are profitable yet (and the company as a whole still loses money), Landau insists most earn back the $500,000 investment within 12 months. A $16 million cushion from Castanea Partners in Boston will help finance growth. Next year, Drybar plans to open 17 new locations for a total of 43.

Landau scoffs at the competition: “A Starbucks is still a Starbucks, no matter how many other coffee shops open on the block.” Turning Drybar into a comparable brand will take all of his highly caffeinated marketing magic and then some.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)