Midea banks on robotics business to stay relevant

The world's largest appliance company makes more refrigerators, ACs and other household items than any firm. Now, with the advantage of its low-cost Chinese labour disappearing, it's entered the robotics business

CEO Paul Fang: 'Globalisation cannot be stopped by any individual or any country.'

Image: Virgale Simon Bertrand for Forbes

The chief executive of the world’s largest appliance company had arrived from China and stood in front of a tough crowd in Augsburg, Germany. Some 3,000 employees of robot-maker Kuka had gathered to meet their new boss. Paul Fang runs Midea Group, and a few days earlier, he had finalised its $3.9 billion-acquisition of the proud German company. The deal had sparked controversy from the shop floor all the way up to the highest ranks of the European Union. Would he shutter the German factories, lay off all its workers and walk off with Kuka’s homegrown technology? Was it wise for Germany to sell a company with such advanced technology to China in the first place?

Fang’s task in that January town hall meeting was to soothe these fears. With thousands of sceptical eyes boring into him, he tried to sell the acquisition as a “win-win” for both companies. “We will work together to develop the market, help Kuka to grow,” he says he told the audience in a short address. “What’s wrong with that?”

Back in his headquarters in Foshan in southern China, a more relaxed Fang was still not certain he convinced the doubters. “When I was standing on the stage, I understood perfectly well that the majority of these people may not be willing to accept the current situation,” he told Forbes Asia. “I tried to think from their perspective, how they feel. It’s not something one meeting can solve.”

But solve it Fang must—not just for the future of Midea, but also for the entire Chinese economy. China’s miraculous growth over the past 30 years has been propelled to a great degree by low costs, which attracted all those factories that churn out the clothes, toys and electronics that fill the world’s store shelves. But as the economy gains in wealth, wages have increased dramatically, eating away at industrial competitiveness. Meanwhile, the local market, once exploding with growth and opportunity, is maturing and slowing down. That leaves Chinese companies with only one way forward—become more innovative, produce more-advanced products and compete on a global scale.

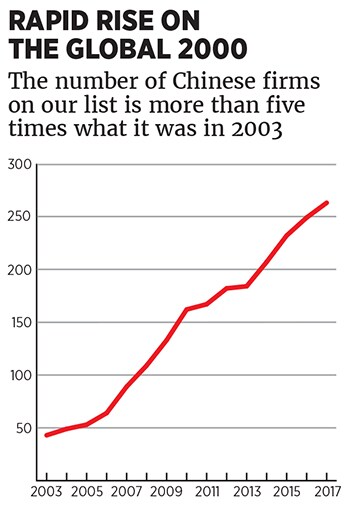

Fang stands on the front lines of this great transformation. With $23.9 billion in sales and $2.2 billion in net profits last year, Midea is already one of China’s most prominent companies, ranking No 335 on the Forbes Global 2000. Last year, Midea sold more consumer appliances—from air conditioners to rice cookers—than any other company. Its global market share, at 5.5 percent last year, is up from 3.9 percent four years earlier, estimates research firm Euromonitor International. In fact, you may have a Midea product in your home and not even know it. The Chinese firm manufactures microwave ovens and other products for famous brands, and it has a batch of joint ventures making air conditioners with Carrier.

Midea was founded in Foshan in 1968 when He Xiangjian collected 5,000 yuan—the equivalent today of $725—and opened a small factory making plastic and glass bottles with 23 villagers. Later, after organising itself into a commune, the company shifted into other products: Auto parts, engines, fans and, in 1984, air conditioners. He, now 74, retired in 2012 and passed the reins to Fang. The founder still owns 34 percent of the publicly traded company, and Forbes Asia estimates his net worth at $13.4 billion.

Fang, 50, hails from even humbler origins. Born in a ten-family village in a mountainous region of impoverished Anhui Province in central China, he spent his childhood fetching water from wells and chopping firewood. He was saved by his smarts, performing well enough on the country’s tough college entrance exam to gain admission to East China Normal University in Shanghai, where he studied history. After graduating, he landed a job at a state-owned factory that made cars and trucks but found the atmosphere stifling. Inspired by a 1992 tour of the country’s south by then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, orchestrated to energise a new wave of economic reform, Fang quit his job and moved to that region in search of opportunities.

He discovered one at Midea, which hired him to edit the company newsletter. Fang describes the Midea he joined as a “small village enterprise”, but he found the environment much more exciting. “The sense of entrepreneurship was really different in a private enterprise than a state-owned factory,” he recalls. “There was a lot to do, and I didn’t have time to do everything I wanted.”

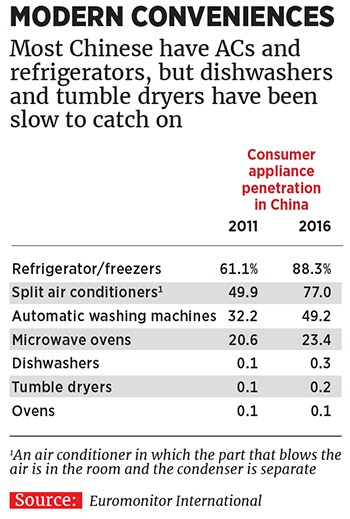

Midea didn’t stay small for long. As China’s economy surged, Midea went along for the ride. Rising household incomes gave the average Chinese family the cash to purchase refrigerators, washing machines and other modern conveniences. And with a population of more than 1.3 billion, there was no shortage of kitchens and living rooms in need. Midea’s sales are roughly 400 times larger today than when Fang joined the company 25 years ago.

Fang has been handed the task of navigating Midea through these new realities. Executives describe him as a hands-off type, who leaves the nitty-gritty details to his top lieutenants while focusing on big-picture strategy. Zachary Hu, president of Midea’s corporate research centre, says Fang has visited his office only twice in the past couple of years, trusting him with the day-to-day management of his department. “Instead of listening to a bunch of specialists, he will try to figure the business out by himself and set the direction of the company,” says Hu. “He is forward-thinking. Even in the good times, we started thinking about the risks facing us down the road and what changes we should make.”

Hu is a key part of those changes. Lured to Midea from Samsung Electronics five years ago, he is now spearheading the company’s efforts to create a more effective research-and-development (R&D) programme. Since 2012, Midea has more than doubled its R&D staff to 10,000 (out of 120,000 employees overall). In April, Midea opened a research centre in San Jose, California, and plans to spend $250 million on it over the next five years.

But Hu cautions that more resources alone don’t translate into innovation. Like many manufacturing firms, he explains, Midea was fixated on improving efficiency and notching quick returns, a management focus ill-suited to fostering creativity. “If you try to drive product leadership, you have to invest for the long term,” he says. “The company culture was not designed that way. They built up [R&D] teams, but they were not doing much. The company had to have a mindset change to deal with the risk of it. That was a huge challenge for us internally.”

Hu started slowly. Rather than assigning his new staff to ambitious endeavours, he first told them to find and fix problems with Midea’s product line. His engineers, for instance, made washing machines quieter and more durable, with better capacity for their size and an easier-to-use detergent dispenser. Such enhanced designs, added to Midea’s especially wide-ranging product offerings and some strong online distribution, have helped boost the company’s market share in China in major household appliances—such as washing machines and refrigerators—to 13 percent in 2016 from 8.7 percent four years earlier, according to Euromonitor data.

Then Hu pressed his teams to create new products. The results included a light, versatile fan and a combination rice cooker and microwave oven. Still, Hu believes that Midea has a long way to go before it invents something completely original. “To try to have a revolutionary product—we’re not there yet. We are still at the beginning of the journey to our final goal.”

That’s true with Midea’s international expansion as well. The company’s global gains have been helped by an expanding presence in key, high-growth emerging markets, such as Vietnam and Indonesia. The company is now investing $160 million in India; a new factory is scheduled to open there at the end of next year. Andy Gu, Midea’s vice president, says the goal is to capture young entrants to the middle class. “They have no preconception of brands, and they need a quality product,” he says.

Midea has also grown through acquisitions. Last year, Fang snapped up majority stakes in the appliance operation of Japan’s Toshiba for $500 million and Italy’s air conditioner maker Clivet for an undisclosed sum, as well as picking up the Eureka vacuum-cleaner brand from Electrolux. Midea’s sales outside of China surged by nearly 30 percent last year, compared with only 5 percent growth in China.

But Midea faces serious constraints to building a global brand. Midea is wary of upsetting its partners by introducing its own, competing product lines in markets where they have a strong presence. Management is also all too aware of the shoddy image that China-made goods have among many consumers, which has caused appliance-rival Haier and other reputable Chinese companies to struggle in many markets. “We’re being very careful with our brand-building initiative,” says Gu. “You have all these small and medium-size Chinese companies that export lousy products. To overcome that perception takes time.”

Midea’s most ambitious global undertaking by far is its acquisition of Kuka. Midea’s management team got the idea to enter robotics from its own troubles keeping factories running at home. Even with wages rising precipitously, recruiting enough staff to fill assembly-line jobs in an economy bursting with opportunities has become a stiff challenge. So Midea has had to rely more and more on automation. One plant in Wuhan, where Midea has invested more than $70 million on automation and information technology since the beginning of last year, has more than tripled the amount produced per worker. “We find it is getting more and more difficult to get people to work for us,” says Gu. “We feel there is a strong need in China for automation, and we found that very few Chinese companies are capable of providing that capability. We have to find some way to fill that gap.”

That led to an interest in selling the robots that Chinese factories need—and in Germany’s Kuka. Fang and his executives argue that their savvy in China could help Kuka’s top-notch industrial robots capture more of that burgeoning Chinese demand. “They can grow, but we can help them grow faster,” says Gu.

The world’s largest appliance company makes more refrigerators, ACs and other household items than any firm. Now, with the advantage of its low-cost Chinese labour disappearing, it’s entered the robotics business

Some politicians in Europe fret that selling a high-tech outfit such as Kuka to the Chinese will undercut the competitiveness of the region’s economy. Günther Oettinger, then-European commissioner for digital economy & society, told a German newspaper last year that Kuka is “a successful company in a strategic sector that is of key importance for the digital future of European industry” and called on its existing shareholders or other companies in Europe to keep it out of Chinese hands. Germany’s vice chancellor, Sigmar Gabriel, who has openly criticised China for failing to reciprocate the free-market openness of the West, reportedly tried to organise just such an alternative bid.

Fang tried to ease such concerns by agreeing to maintain Kuka’s plants and workers in Germany until 2023. He has also kept management in place and intends to operate the robotics company as a separate unit. Though Gu is now chairman of Kuka’s supervisory board, he visits only once a month for meetings, and Midea has posted no Chinese staff full-time to Augsburg. “It is a different environment, different culture,” he says. “We leave them alone to run the business.”

Still, Midea’s managers realise they have bridges to build. “There is this China monster that comes to your country, that grabs your jobs—that perception is still there everywhere,” says Gu. “You cannot change it overnight.” Fang knows as well that Midea’s experience in Germany is part of something bigger and more daunting for a Chinese company with global ambitions: Rising economic nationalism. Yet he believes that this sentiment will eventually pass. “There are anti-global trends now, but you have to look at things from a long-term perspective,” he says. “Globalisation is a major trend and cannot be stopped by any individual or any country.”

That leaves Fang confident about the future of Midea—and China. “Chinese companies are going global,” he says, “and this trend will not change.”

(With reporting by Yue Wang)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)