Michael Steinhardt, Wall Street's Greatest Trader, Returns

Michael Steinhardt forged the model for making hedge fund billions before exiting the game. With WisdomTree, he's back to upend Wall Street again—this time, with the little-guy investor at his side

During the three decades that Wall Street grew up, morphing from a gentlemen’s investment club into a global financial colossus, Michael Steinhardt emerged as the world’s greatest trader. From 1967 to 1995 his pioneering hedge fund returned an average of 24.5 percent annually to its investors, even after Steinhardt took 20 percent of the profits. Put a different way, $10,000 invested with Steinhardt in 1967 would have been worth $4.8 million on the day he shuttered his fund. (The same investment in the S&P would have been worth $190,000.) It was a performance that landed him on The Forbes 400 in 1993, with a net worth estimated at more than $300 million.

Trading is all about timing, and by one key measure, he failed. He walked away while in his 50s, just as the hedge fund industry, which he helped create, was becoming the most potent moneymaking machine ever invented. Had he stuck with it, he very likely would be one of the very richest people in the world, mentioned in the same breath as George Soros ($20 billion) and Steve Cohen ($9.4 billion).

“I thought there must be something more virtuous, more ennobling to do with one’s life than make rich people richer,” says Steinhardt. “There’s no sin in making rich people richer, but it’s not the sort of thing from which you would go straight up to heaven.”

Steinhardt says this in the most gentlemanly—even grandfatherly—way, a far cry from the notoriously short-tempered “screamer” of his heyday. He leisurely charts his life away from Wall Street, a tale that touches on politics (he was an early Bill Clinton supporter), Jewish cultural values (an atheist, he is nonetheless an ardent supporter of Jewish causes), animals (his country estate houses one of the world’s largest private zoos) and even a type of French field strawberry, the fraise du bois, that his wife, Judy, once tried to grow commercially.

But sitting behind a glass desk in his thickly carpeted Manhattan office, Michael Steinhardt has another message that Wall Street should take note of: He’s back, and rather than play by the rules that he helped establish, he’s blowing them up, positioning himself as an advocate for the little guy—and making himself a new fortune in the process.

Steinhardt is chairman of the board and, with a 14.7 percent stake worth some $330 million, the largest single stakeholder in WisdomTree Investments, the ETF shop created by Jonathan “Jono” Steinberg, son of the late corporate raider Saul Steinberg, who famously flamed out at the end of his career. Steinhardt was way early on hedge funds— his was among the first dozen (there are 8,000 today). He thinks exchange-traded funds have similar disruptive potential, with individual investors (and some savvy operators like him) reaping the benefits.

“I cared about one thing,” Steinhardt says of his trading years, “and that one thing was having a better performance than anybody in America.” He later adds: “I want to phrase this in the strongest possible way: Jono Steinberg has been, from my perspective, the single greatest manager in the world of money management during the last eight or nine years.”

Whoa! To the extent that Wall Street has a take on Jono Steinberg, it’s that he’s married to Maria Bartiromo, business television’s “money honey”. In the 1980s he failed to complete his undergraduate business degree at Wharton (Steinhardt’s alma mater), despite the fact that his father’s name is carved on one of the buildings. He later used his family’s money to rechristen a tout sheet called Penny Stock Journal into Individual Investor magazine, which went bust in 2001. Most critically, the man Steinhardt calls the greatest money manager of his generation has never managed a significant amount of anyone else’s money.

And that, of course, is Steinhardt’s point. Exchange-traded funds typically charge lower fees and have tax advantages over traditional mutual funds. They are also completely transparent: An obsessive-compulsive ETF investor can check his fund’s holdings daily, rather than quarterly, as is the norm for most mutual funds. This magic combination—cheaper with lower taxes and greater transparency (and often for the same underlying investment)—means that over time ETFs will eat the lunch of the $12.1 trillion (assets) mutual fund industry.

With $35 billion under management, WisdomTree has only a 2.1 percent share of the $1.7 trillion (assets) ETF market, but that’s up from less than 1 percent in 2010, and it has been steadily chipping away at BlackRock and State Street, which have a combined 61.9 percent market share. The company uses academic investment theory to create ETFs that seek to consistently outperform the market, albeit just by a point or two. It’s a far cry from Michael Steinhardt’s S&P-crushing performance, but it’s one that is available to everyone, not just a select few.

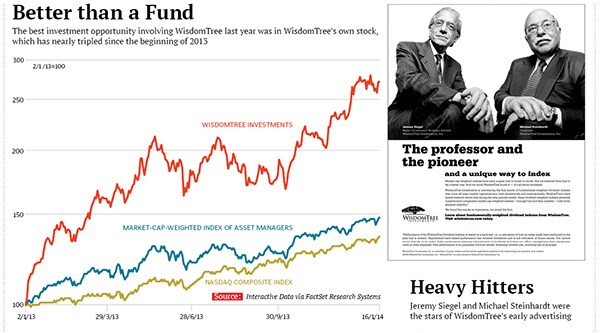

WisdomTree is also the only pure-play, publicly traded ETF manager. Since the beginning of last year its stock is up 171.9 percent versus 35.6 percent for the Nasdaq Composite and 47.7 percent for a market-cap-weighted basket of comparable asset managers.

Given that performance, Jono Steinberg might be the best money manager of the past year—to the extent that he made Steinhardt a killing. Steinhardt, meanwhile, is no longer a legendary hedge fund has-been. He is poised to have been in the van-guard of two revolutionary investment trends—two that happen to be diametrically opposite.

When Michael Steinhardt started Steinhardt, Fine, Berkowitz & Co (later just Steinhardt Partners), it was, literally, a “hedge” fund—a fund, as the term implies, equally willing to short stocks as to bet long, thus providing a hedge against down markets, of which in the ’60s and ’70s there were many.

“I really shorted a lot. I liked to short,” says Steinhardt. “I felt far more gratification from making money on the short side than from the long side, which is a very dangerous thing, because the short side is so tough.”

The fledgling fund’s sharp-elbowed operators did indeed protect their investors in bad times—Steinhardt even made money during the horrendous 1973–74 bear market—but what turned heads was the outsize returns they popped, regardless of investing climate. “He’s a legend and a terrific money manager,” says hedge fund billionaire Julian Robertson Jr, who started 13 years after Steinhardt.

“For me, running hedge funds was an art. It was something that I thought I did exceptionally well, and most of the world did not. But they didn’t care the way I did,” says Steinhardt. “I got depressed if I was having a bad day, a bad week, a bad year.”

Steinhardt was an aggressive, instinctual trader whom many considered the worst boss on Wall Street. His employees “used expressions like ‘battered children’, ‘mental abuse’, ‘random violence’ and ‘rage disorder’ ” to describe working at his firm, he recounts in his autobiography, No Bull: My Life In and Out of Markets.

“When I did well, I was happy,” Steinhardt says. “When I did poorly, I was intolerant and difficult and had a bad temper.”

Almost from the beginning there were whispers in the more civilized—and lower-performing—corners of Wall Street that hedge fund shops like Steinhardt’s were cutting corners. There seemed to be no other rational explanation for their returns. But hedge funds were considered a small sideshow for “qualified” investors, and the SEC had other priorities than protecting rich people from taking advantage of other rich people.

By the early 1990s, however, all of that had changed. Flush with institutional cash, which had arrived in bulk during the ’80s, the original hedge funds were now huge and their managers were growing megarich as they emerged as Wall Street bullies. Steinhardt, who had started with $7.7 million under management in 1967, was now running $5 billion and increasingly placing massive macroeconomic bets in the bond markets.

In 1991 the SEC began investigating four hedge fund managers—Steinhardt, Soros, Robertson and Bruce Kovner—for colluding with Salomon Brothers to corner the market in two-year Treasury bills. Robertson and Soros were eventually dropped from the investigation, but in 1994 Steinhardt, Kovner and Salomon agreed to pay to settle the allegations. Salomon coughed up $290 million—then the second-largest fine in Wall Street history—while Steinhardt Partners paid $70 million, 75 percent of it coming out of Michael’s personal pockets.

It was an annus horribilis for Michael Steinhardt in another way, too. His fund would end 1994 down 31 percent after making an ill-timed wager on foreign bonds. It was far and away the worst performance he had ever turned in for his clients. He vowed to make them back as much money as possible. The next year he was up 26 percent. Then he quit.

“Having grown up in a lower-middle-class Jewish neighbourhood in Brooklyn, I didn’t know what to do with all this money,” he says.

“It didn’t interest me, all this money. What interested me was to be the best manager, doing the best job, achieving the best rates of return for my investors.” If he wasn’t going to be America’s best money manager, he wasn’t going to manage money at all.

When assessing a money manager’s performance, Wall Street types distinguish between beta—the return of the overall market, usually measured by some benchmark index like the S&P 500—and alpha, the amount by which the manager was able to outperform the broader market. You’re measuring what kind of return you get beyond if you just picked 1,000 stocks out of a hat. Alpha is the only reason to pay someone to manage your money, and it’s vanishingly hard to find: One long-term study of mutual fund managers concluded that in the 30 years between 1976 and 2006 only 0.6 percent exhibited any consistent skill at beating the market, and nearly 25 percent of these financial “pros” posted returns with negative alpha. Hedge funds aren’t doing any better: One recently published report concluded that just 16 of the largest 100 beat the S&P last year.

“There are more of them,” says Robertson, “which means that there is more competition for all of them.”

Research like this, which has been replicated for a wide variety of investment strategies under all sorts of market conditions, is often used to support an academic theory of the financial markets called the efficient market hypothesis. The theory postulates that all available information is already contained in the price of an individual stock, and the ugly consequence is that no one can consistently beat the market, nor should they try.

Instead they should buy beta and be the market, and do so at the lowest possible price. Ultra-low-cost index mutual funds, managed by formulas rather than people, were developed as a direct response to this sort of thinking. The most famous of these funds, the Vanguard 500 Index Fund, was created in 1975 to allow retail investors to replicate the S&P 500 at a very low cost (currently 0.17 percent of assets). It has $160 billion in assets, about 1.3 percent of the entire domestic mutual fund industry.

But the efficient market hypothesis can run counter to common sense—the theory doesn’t allow for market bubbles, for instance, since it insists that all assets, whether Florida real estate in 2005 or internet stocks in 1999, are always properly priced for their level of risk. It ignores the fact that information is not shared and interpreted evenly. And it shrugs off star traders like Michael Steinhardt as very lucky outliers.

“If you believe that causal outperformance is impossible, then you would also say that asset bubbles are impossible,” says Frank Salerno, who joined WisdomTree’s board in 2005 after a long career at Bankers Trust and Merrill Lynch. “I think you have to temper your basis in financial theory with what goes on in the real world.”

And it was in the wake of one of the biggest asset bubbles of recent history—the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s—that some people began to seriously rethink stock indexes. What if instead of weighting by market capitalisation—which during the bubble resulted in investors having greater and greater exposure to stocks whose price had gone up a lot—you created an index that was weighted by fundamentals like profits and dividends? Could such a product reliably outperform the broader market over long periods of time? It wasn’t alpha—these indexes would be managed by computers and algorithms, not the instincts of Wall Street pros—but it wasn’t pure beta either. It was, for lack of a better word, beta-plus.

At the company that would become WisdomTree, three very different men came together around this vision. The first was Jeremy Siegel, a well-respected finance professor at Wharton and bestselling author who had famously warned of the bubble in technology stocks in early 2000.

The second was Jono Steinberg, who was seeking redemption after the subsequent dotcom collapse destroyed his business. And the third was Michael Steinhardt, the master of pure alpha, who after a decade-long hiatus would soon return to The Street as the champion of smart beta.

Jono Steinberg first learned about ETFs in 1997, while he was still running Individual Investor magazine, and the “lightbulb went off right away”.

“When the liquid, transparent, tax-efficient structure of the ETF became apparent to me, I had an idea that if you could create a better index and marry it to the ETF-structure, you could give investors a better investing experience,” he says.

But for years the idea remained just that—an idea—as Jono and his publication rode the great bull market. When the stock market crashed in March 2000, it was hard on financial publications across the board, but the ones that had cheered loudest got hit the worst. In the summer of 2001, with advertising reportedly off by a third and his stock delisted (he claims voluntarily) from Nasdaq, Steinberg was forced to shutter Individual Investor and fire its staff. He sold the magazine’s subscriber list to Kiplinger’s, but he kept the rights to a performance-weighted stock index called America’s Fastest Growing Companies. On the strength of that and his increasingly distant glimmer of an idea about ETFs, he renamed his company Index Development Partners in 2002 and went knocking on doors. And knocking.

“He pitched it everywhere,” says venture capitalist Jim Robinson IV, whose firm, RRE Ventures, initially passed on Jono’s idea. (Robinson’s father, and the founding general partner of RRE, is Jim Robinson III, who ran American Express from 1977 to 1993.) “We knew ETFs sounded interesting, but we were worried about how a small, unknown company could emerge. And, frankly, we weren’t sure how you got from the magazine business to that.”

A couple of months later, Jono Steinberg called back and told Robinson—whom he had known for more than a decade—that he had a big fish nibbling on the line: Michael Steinhardt seemed interested. But Steinhardt would invest only if Jono could find someone to go in with him. After a certain amount of wrangling with his partners, Robinson agreed, and in 2004 RRE and Steinhardt invested a combined $9 million in Index Development Partners, which was renamed WisdomTree the following year. It was the company’s entire capitalisation.

“I invested with Jono because I felt throughout my investment life that the average guy was not served well by Wall Street,” says Steinhardt. “He dealt with some schlubby broker. He dealt with some schlubby mutual fund. And none of this was truly competitive with others who had more insight or more money. I thought that Wall Street was not a great place in terms of it serving the interests of those who most needed to be financially served.

“He had a reasonably intelligent approach to outperforming the averages,” Steinhardt continues. “It wasn’t going to outperform the averages like a hedge fund, but it was going to outperform.”

And Steinhardt being Steinhardt, he made a terrific trade, buying into WisdomTree a total of “two or three times” for just pennies a share (the stock recently closed at $17.59). Jono Steinberg owns just 4 percent. In absolute, on-inflation-adjusted figures, Steinhardt has made more from his WisdomTree investment than he did in 28 years of running a stellar hedge fund. At last count there were 30 American hedgies on the Forbes list of the world’s billionaires, but it’s only after WisdomTree’s recent performance—added to his old Wall Street stash and extensive art collection—that Steinhardt has, for the first time, qualified himself.

Steinhardt’s investment brought instant viability to WisdomTree, but the company still needed someone to bring more intellectual heft to the concept of fundamental weighting than Jono could plausibly provide. Fortuitously, Jeremy Siegel, who knew Jono slightly from a prior life as a columnist for Individual Investor, was already thinking along the same lines.

“I had been a big advocate of Vanguard and market-cap weighting,” Siegel says. “It was as a result of the internet bubble in 2000 that I began to rethink my position. I looked at my portfolio and said, ‘Gee, I wish I didn’t hold these tech stocks. There must be an index that we can devise that would underweight stocks that appeared to have gone way outside their fundamentals in terms of price.’ That’s what got me interested in exploring alternative indexation.”

Siegel took Jono’s indexes and, with a research assistant, spent an entire week running them against an enormous database of historical stock prices. He was impressed enough—“using very long-term data there is statistically significant outperformance by fundamentally weighted indexes”—that, in return for WisdomTree stock, he was willing to lend his name and reputation to

the embryonic company. At one point, if you include shares he had purchased, he owned 2 percent of the company; he has since partially cashed out.

The secret to that outperformance, according to Siegel, is what investors like Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett have preached all along: Value.

“People overbuy growth stories,” Siegel says. “They pay too much for growth stocks. They ignore value stocks. They ignore slow growers. They tend to be underpriced. Therefore over the long run you are going to get a better return.”

With Siegel and Steinhardt providing their own Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval, WisdomTree was able to lure Salerno, the former Merrill exec, out of retirement to advise on the nitty-gritty of building the business. (“They had an idea,” Salerno says. “They didn’t have anyone with asset-management business experience to make it happen.”) Arthur Levitt, who had been chairman of the SEC from 1993 to 2001, was brought on board to help grease the skids with regulators. Levitt had just taken command of the SEC when Steinhardt paid the $70 million fine that helped drive him from the hedge fund business. Levitt says he didn’t know him then. As allies, though, he says that it’s Steinhardt who put the wisdom in WisdomTree. “I have huge admiration for an individual who is so multidimensional, which isn’t a characteristic of most people I have dealt with on Wall Street.”

Since WisdomTree’s inception, 85 percent of its assets have outperformed their peers, as tracked by Morningstar. But that’s a little bit misleading, since a full 49 percent of its assets are concentrated in just two funds—the Japan Hedged Equity fund (36.5 percent) and an Emerging Markets Equity Income fund (12.5 percent). The Japan fund, which lets US investors bet on big Japanese companies while zeroing out the currency risk, has been killing it since the Bank of Japan began more aggressively easing its monetary policy last year. Through 2013 the fund accounted for $9.8 billion of WisdomTree’s net asset inflows, or 68 percent of the total. It has nothing to do with what WisdomTree promotes as its special sauce: Beta-plus, or fundamental-weighting.

By the company’s own reckoning, 14 of WisdomTree’s current 61 ETFs are pure beta-plus equity plays, although many of its other products contain elements of fundamental weighting. Since inception, 10 of the 14 funds have outperformed their benchmark indexes—some dramatically. But all four of its domestic dividend-weighted funds have underperformed.

“They have had six or seven years to try it, and so far they have proved nothing: N-O-T-H-I-N-G,” says John C “Jack” Bogle, the founder of the Vanguard Group and intellectual father of the low-fee index fund, spelling out the last word for emphasis. “You can’t say it works, you can’t say it doesn’t.”

He continues: “That original fund idea, which had a certain amount of intelligence to it—it wasn’t a guarantee that you were going to win, but it was certainly a guarantee that you wouldn’t lose too much and you might win—it now represents just 5 percent of their assets under management. WisdomTree is a marketing company trying to find something that the public wants.”

To that, Steinhardt shrugs. In his years running a hedge fund, he was famous for changing his mind in a heartbeat—there are stories of Steinhardt closing out a trader’s entire position while he had stepped out to grab lunch. While he remains a firm believer that beta-plus will beat the market over the long haul, if the market wants a Japanese-currency-hedged fund today, that’s what WisdomTree will sell them. “It just proves that they are continuing to innovate,” Steinhardt says.

In the meantime, WisdomTree has used Steinhardt’s name and likeness in its marketing and advertising to let financial advisors know that its ETFs are safe and warm. The original hedge fund terror as a 21st-century Charles Schwab? Just your everyday Wall Street turnaround.

Michael’s Menagerie

Steinhardt calls his 57-acre estate in Bedford, N.Y.—which is within camel-spitting distance of Martha Stewart’s country home—“the only physical possession in my life from which I really derive great pleasure”.

The property is a veritable Noah’s Ark of exotic animals and edible plants: There are 90-year-old land tortoises, playful marmosets, African servals, rare zonkies (half-zebra, half-donkey) and apple-munching camels (above). And “oodles and oodles of berries”: Gooseberries, jostaberries, currants, blackberries, blueberries, huckleberries and cranberries. “I wanted to grow every conceivable berry.”

In the fall the maple garden, which contains 400 to 500 trees of many varieties, blazes brilliant red. It is, as Steinhardt puts it, “amazingly beautiful. It almost lights up the sky it’s so beautiful with its colour”.

—MN

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)