Medidata Solutions: Using Software to Make Better Drugs

Medidata Solutions believes software can revolutionise the way Big Pharma develops new medicines. It has Oracle in its sights

Tarek Sherif, a small-time fund manager, plopped his desktop computer on an office chair and wheeled it a mile down Park Avenue from his office into a small room and toward the desk that he would share with a young tech entrepreneur he’d met through his college roommate—a tech entrepreneur named Glen de Vries.

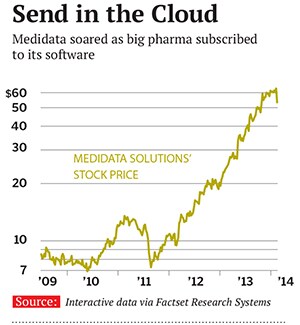

From this inauspicious start in 1999, the two men built something astounding: A 1,000-employee, $277 million (sales) technology company called Medidata Solutions. They make software that drug companies use for running and tracking clinical trials in the cloud, taking on tech giant Oracle for dominance of this growth-rich health care niche. Drugmakers welcome Medidata’s software platform, which allows them not only to enter data but also monitor studies on a large scale, potentially slashing runaway costs. Medidata keeps track of 8 billion clinical records for half a million patients, with 1,400 more patients entered into its systems every day. “We believe where they’re going as an organisation supports the new trend in the industry to really change the way clinical trials are done,” says Kim Grebel, senior director of strategic business improvements at Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a unit of Johnson & Johnson.

“This whole concept of creating value in drug development is starting to take hold,” says Sherif. “How do you reduce your costs but increase your value with better drugs that get paid for?”

Sherif, the chief executive speaks softly and philosophically; de Vries, the president, who coded Medidata’s original software, is a born salesman. In their ultramod 140,000-square-foot downtown Manhattan headquarters, they still share an office, and at a recent company party dressed as Batman and Robin look alikes. In separate interviews the two men gave the exact same quote: “We’ve never had a fight.”

De Vries first decided to create a startup to digitise the process of conducting clinical trials in 1994, shortly after earning a degree in molecular biology from Carnegie Mellon. He went to work in a lab at New York’s Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital and was assigned to help design a small clinical trial. He was shocked by the mountains of paper and lack of computer tools. He and a urology resident, Ed Ikeguchi, also a proficient programmer, decided to start a company. “We really were looking at Amazon,” de Vries says. “If you can get to Amazon.com and buy a book, presumably that’s secure, it’s efficient, why can’t we be doing clinical trials that way?”

Sherif joined in 1999, as they restarted as a new firm. Initially he was just a potential investor, but he became so fascinated that he and de Vries wound up working side by side. Initially all three men were partners without titles. But in 2002 they did a $1 million venture round and Sherif became CEO. The fact that clinical trial doctors and nurses liked the trio’s software led to early deals with small biotechs. Medidata was cash flow positive, but in 2004 Sherif and de Vries did a $10 million financing with Insight Venture Partners in Manhattan so Medidata could claim it was the second-biggest electronic data capture firm, after Phase Forward.

Medidata’s software was different from its rivals’ because it is what is known as “software as a service”, similar to the model pioneered by Salesforce.com. The company provides fewer direct services for its clients and focuses on creating subscription-based software that clients can use themselves. This model caught on—and did particularly well with Japanese drug companies, with which Ikeguchi built relationships from scratch. Sales tripled to $106 million between 2005 and 2008. In the space of a year head count went from 50 to 170, and that doesn’t include about 50 employees who left. “I always point to it as the time when I went grey,” says Sherif.

But even J&J, Medidata’s big customer, admits to “growing pains” in using the company’s technology. When backlog looked light in the fourth quarter, the stock dropped 9 percent. “They have a great, great business model. It’s just a wildly expensive stock,” argues Gene Mannheimer, an analyst at B Riley & Co. Six of the seven other analysts covering Medidata disagree and still say “buy”.

To keep growing Medidata is going to do more than just keep track of the data entered into a new clinical trial. It’s going to help drugmakers that spend billions of dollars in R&D for each new drug figure out where they are wasting money. Among the new feats claimed by Medidata: Allowing researchers to be trained only once, instead of having to get re-educated for each study; cutting the time it takes for doctors to electronically ‘sign’ each clinical document, saving 9,000 hours a year over its client base; reducing the cost of preventing bad or fraudulent data in a late-stage drug study by an estimated $30 million; and using FitBits or other wearable devices to collect data instead of dragging patients into an office.

Sherif and de Vries insist it is just the beginning. “We were naive in a very good, useful way,” says de Vries. “It wasn’t a zero-sum game. The enemy was paper.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)