Martin Varsavsky has a bold plan to turn the infertility industry on its head

Serial entrepreneur Martin Varsavsky has a $200 million war chest built around persuading women to freeze their eggs while they're young. Decisions about career, mates and motherhood will never be the same

Image: Timothy Archibald for Forbes

Even among the hyperactive overachieving techies in his cohort, Martin Varsavsky stands out. He’s built more successful businesses—six—than all but the most prolific serial entrepreneurs. He’s also fathered more children—six as well—than all but the most prolific dads. Yet at 56, Varsavsky, one of the most recognisable figures in Europe’s tech scene, is going for something of a “lucky seven”. Twice.

After moving to the US from Spain two years ago, he set to work launching another company. And his wife, Nina, is expecting another child in January, their third together. “We call him Seven for now,” Varsavsky quips. The two sevens are inextricably linked. His new startup, Prelude Fertility, whose story is being told here for the first time, has a bold plan to turn the infertility industry on its head. Varsavsky isn’t just Prelude’s founder—Seven, his upcoming child, will be the first “Prelude baby”.

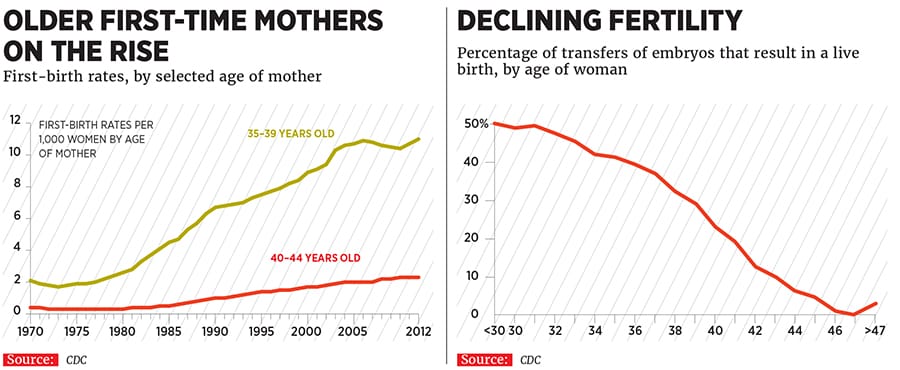

Armed with $200 million, Prelude plans to take the technology of infertility—in vitro fertilisation (IVF)and egg freezing—and aggressively expand it into fertility, hoping to usher in a world where women’s decisions about family and career aren’t ruled by their biological clocks. Rather than cater primarily to women nearing the end of their childbearing years, who often find it harder to conceive, Prelude will target women in their late 20s to mid-30s, when it’s easier to harvest eggs and when those eggs are more likely to lead to healthy babies. As women increasingly delay childbirth—nearly one in three in America now has her first child after 30 and nearly one in ten after 35—Prelude sees itself as an insurance policy that gives women more control over their childbearing choices. “We’re about helping women and couples have healthy babies when they’re ready,” Varsavsky says.

Prelude isn’t the first company to urge women to think about fertility earlier in life. While some critics decry egg freezing for younger women as a risky, often unnecessary, procedure that can give them a false sense of security and increase pressure to put career before family, a gaggle of new businesses with names like Extend Fertility and EggBanxx have sprung up to serve them, offering financing plans that make it easier to cover the procedure, which can cost $5,000 to $10,000 or more. (Adding IVF can easily double the cost.) Two years ago, Apple and Facebook became the first major companies to offer egg freezing as a benefit, and this year, the Pentagon launched a pilot programme that pays for egg and sperm freezing, part of an initiative to retain troops.

But Prelude aims to take the idea mainstream, giving it scale and Silicon Valley pizzazz. Varsavsky has already put his war chest to work, spending, it’s estimated, tens of millions of dollars to buy a majority stake in the largest in vitro fertilisation clinic in the Southeast, Reproductive Biology Associates (RBA) of Atlanta, and its affiliate, My Egg Bank, the largest frozen donor egg bank in the nation. The acquisitions anchor what Varsavsky hopes will eventually become a national fertility brand. Rather than offer services piecemeal, like egg freezing, storage, IVF and hormonal medications, Prelude will pitch a comprehensive package it calls the Prelude Method. It includes four steps: Egg freezing and preservation, embryo creation when a woman is ready, comprehensive genetic screening for congenital diseases and chromosomal abnormalities, and “single embryo transfers” to minimise the chances of conceiving twins or triplets, a frequent occurrence when women transfer multiple eggs during IVF. (Prelude, which hopes to cater to couples who may not be ready to have children, will also offer sperm freezing for men.) Prelude also plans to make the process more affordable, offering options with low upfront fees. Keeping the eggs safe and frozen, however, will start at $199 a month.

Prelude is betting that young women will pay a few grand a year to alter the equation between career and family. “If you know that your eggs are safe and sound, what decisions would you make about your life?” says Allison Johnson, a former top marketing executive at Apple who helped to launch the iPhone and who overcame her own fertility issues with hormonal treatments. Her agency, West, is helping to develop Prelude’s go-to-market plan. “That what’s really exciting about this,” Johnson says. “Go pursue that graduate degree. Wait for your soulmate. Go travel the world. Your eggs are waiting for you. For me, that’s as liberating for women as the pill was in the ’60s.”

Varsavsky began thinking about Prelude about six years ago. A tech entrepreneur who has long had an interest in lifesciences, he hit a snag in his life when he and Nina tried to start a family. Nina, 31 at the time, found out she was infertile shortly after the couple married. They were able to conceive their first child through IVF—and froze their eggs and sperm for future use. They now have two healthy children, aged 5 and 3, and that third one on the way, all conceived through IVF, but the experience was wrenching. (The couple also went through a battery of genetic tests, many of which will be part of the Prelude Method.) And the Varsavskys knew couples who weren’t able to conceive through IVF. The data confirm their experience: Twelve percent of American women aged 15 to 44 face difficulties having a baby on their own, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC).

Ever since his childhood in Buenos Aires, Varsavsky has looked for unique opportunities in big markets. His family immigrated to the US in the 1970s as refugees after his cousin David Varsavsky was murdered—“disappeared”, in the euphemism of the time—by the Argentine military government. While in graduate school at Columbia University, he launched a real estate company that converted industrial buildings into residential lofts. Two years later, he and fellow Argentine César Milstein, a Nobel laureate in medicine, co-founded a biotech company called Medicorp Sciences, now based in Montreal, that developed an early AIDS treatment.

In the 90s, Varsavsky turned his attention to a string of telecom endeavours. The first, Viatel, founded in 1991 in New York City, provided low-cost long-distance calling. It went public within three years. In 1995, Varsavsky moved to Madrid and started Jazztel, a provider of telecom and internet services that went public in 1999. He then launched Ya.com, a DSL provider and internet portal sold two years later to Deutsche Telekom. His next company, a German applications service called Einsteinet, failed quickly, personally costing him $50 million. No biggie. The string of successes left Varsavsky with a net worth that Forbes estimates at $300 million.

After lying low following the dot-com crash, Varsavsky founded Fon, an outfit with an ambitious plan to create a global network of “Foneros”, who would share their Wi-Fi connections with one another, allowing users on the go to connect to the internet anywhere in the globe. The startup, which was backed by Google, Skype, Sequoia Capital and Index Ventures, has grown to more than 20 million users. After the company became profitable last year, Varsavsky says, he decided to step down as CEO (he remains chairman) to focus full-time on fertility.

Prelude was officially born in 2015. Varsavsky realised that the typical tech startup model wouldn’t work. Because of regulation and other hurdles, he decided it would be best to buy into an existing fertility clinic and egg bank. That meant he would need to seek funding from private equity rather than venture capital. He settled on Lee Equity Partners, which focuses on middle-market transactions and had been eyeing the potential of the IVF business.

The IVF industry in the US has everything private equity likes—scale (about $2 billion annually) and growth (more than 10 percent a year), along with being fragmented and having outdated marketing. It’s an industry associated with failure: Roughly two-thirds of IVF cycles produce no baby, according to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART). By freezing women’s eggs before their fertility starts to wane, Prelude should be able to tell stories of success. With its initial purchases—the thriving RBA practice and My Egg Bank, which freezes roughly 40 percent of all donor eggs in America—Prelude is already profitable, on revenues estimated at about $35 million. And it’s poised for continued growth. “We intend to expand nationally and partner with leading clinics in the US,” says Collins Ward, a principal at Lee Equity.

Techniques for egg retrieval and freezing, officially called oocyte cryopreservation, have been around for more than 30 years and were often used as a way to preserve fertility in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Women typically go through a course of fertility drugs that stimulate the ovaries to produce eggs. Doctors then extract the eggs with a needle that pierces through a vaginal wall into the ovary. Because an egg, unlike embryos, is a single cell made up mostly of water, the standard slow-freezing technique often produced ice crystals, making the eggs unusable.

In the past decade, vitrification, a new flash-freezing technique, has vastly improved success rates, leading the American Society for Reproductive Medicine to remove the “experimental” label from the process in 2013. However, the group issued a warning: “Marketing this technology for the purpose of deferring childbearing may give women false hope and encourage women to delay childbearing.”

As of now RBA, tucked in a suburban Atlanta office park, serves as Prelude’s nerve centre. To visitors it looks like a standard medical office, with waiting rooms and exam rooms along corridors painted in pastels and adorned with soothing images. Behind the scenes, several technicians work inside a large lab, some staring into microscopes and some at computer screens, amid an array of equipment that includes several large incubators. There’s a mechanically controlled machine that allows a technician, watching through a microscope, to use a tiny syringe to pierce the membrane of an egg and fertilise it with sperm. Next to the lab is a large storage room filled with cryopreservation tanks, wheeled 3-foot-tall units shaped like small R2-D2s. Each is filled with liquid nitrogen and preserves embryos and eggs at –321 degrees Fahrenheit.

Until recently, the number of women who have chosen to freeze their eggs to preserve fertility options was relatively small (6,200 in 2014). But after Apple’s and Facebook’s announcements of egg-freezing benefits and as celebrities like Sofia Vergara and Kim Kardashian have gone public about the procedure, fertility doctors are reporting a surge of interest.

There’s no dispute that banking eggs earlier in life improves outcomes. RBA’s Dr Zsolt Peter Nagy, who helped pioneer vitrification techniques, says an egg extraction in a 32-year-old woman will typically yield between 15 and 20 eggs, which would eventually result in about 10 to 14 fertilised eggs and 4 to 8 usable embryos. A 40-year-old patient, meanwhile, would typically produce between 4 and 15 eggs but end up with fewer than 3 usable embryos—and in some cases none. As a result, an IVF cycle with eggs from a 32-year-old woman has a roughly 50 percent chance of resulting in a live birth, according to data from the CDC; the figure drops below 20 percent for a 42-year-old woman.

But there are plenty of sceptics and critics. While egg extraction and freezing is safe in most cases, the required injections can cause swelling and discomfort. In a small number of cases, complications require hospital care. “Retrieving multiple eggs involves injections of powerful hormones, some of them used off-label and never approved for egg extraction,” Marcy Darnovsky, the executive director of the Center for Genetics & Society, said in a widely cited critique. “The short-term risks range from mild to very severe, and the long-term risks are uncertain because they haven’t been adequately studied.” Others say the industry is putting profits ahead of safety. And cost is an issue, too, especially since most of the frozen eggs will never be used. In 2014, only 1.6 percent of babies born in the US were conceived through IVF, according to SART, whose data cover more than 90 percent of the clinics.

Varsavsky is aware that Prelude is jumping into sensitive territory. But he’s driven by the conviction that infertility in all its forms—the ability of a woman not only to have a child but also to have as many as she wants—takes an increasingly painful toll on families. Prelude—not counting the staff of roughly 100 at RBA and My Egg Bank—remains tiny, with just five employees, and almost all of them have been touched by infertility, giving the company a sense of mission. “The emotional part is driving what we are trying to do,” says Tia Newcomer, Prelude’s chief revenue officer, whose husband is a cancer survivor who opted not to freeze his sperm when he was diagnosed at the age of 18, forcing them to seek the help of a sperm donor in order to have children.

From Johnson’s offices at West in the San Francisco Presidio, which Varsavsky uses as temporary headquarters, Prelude is developing a marketing campaign that promises to focus on education rather than fear. That will include encouraging women and their ob-gyns to test more routinely for a hormone, AMH, whose levels can determine the likelihood of infertility. And Varsavsky is plotting to take the company national by partnering with a network of clinics that will offer the Prelude Method. The advertising push is expected to begin this month. “The science of Prelude will work,” Varsavsky says. “If we fail, it’s because we fail in making Millennials to think ahead.”

Millennials, it should be noted, are known to fixate on getting what they want—when they want it. Why should procreation be any different? “One of the changing elements in health care is consumer choice, and I think that Martin is introducing that in the fertility sector,” says Anne Wojcicki, the founder and CEO of genetic-testing company 23andMe and a friend of Varsavsky’s.

One recent academic study asked not whether it is a good idea for younger women to freeze their eggs but when was the optimal time to do so. Dr Tolga Mesen, the lead author, plugged variables such as rates of marriage, pregnancy and miscarriages, and even cost, into a model to determine the probability of success and the likelihood the eggs would be used. While most women will never need to freeze their eggs, Mesen said, the procedure can be life-changing for some patients.

The ideal age to do it? Between 31 and 33. Young enough to make Varsavsky’s seventh startup his biggest, if American women buy in.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X