Marc Benioff's audacious plan to reinvent Salesforce

In an age that celebrates manic entrepreneurs, none is more frenetic than the Salesforce founder, whom we consistently rate as America's most innovative CEO. Come along for a wild ride with Marc Benioff as he tries to turn hyperactivity into a new model for tech growth and corporate activism

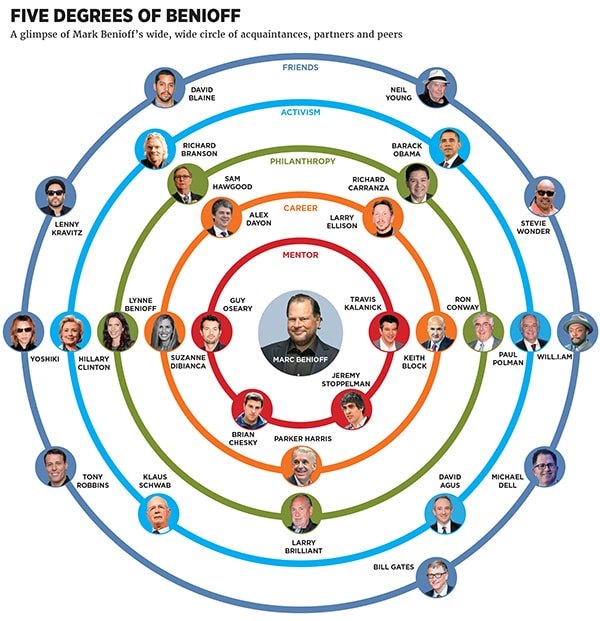

Salesforce co-founder Marc Benioff spends several months a year in Hawaii, where he owns a sweeping beachfront house on the Big Island and pals around with billionaire Michael Dell and ageing rock star Neil Young. Little surprise, then, that for a retreat with 400 of his top executives in August, he has summoned them to an air-conditioned ballroom near the white sands and volcanic cliffs down the shore.

In this expected venue an unexpected scene plays out: Benioff, his massive 6-foot-5 build wrapped in a white Hawaiian shirt patterned with blue palm trees, his head topped with a Mauna Kea baseball cap, begins speaking to his co-founder in German.

“Ja, ja, ja,” Benioff grins.

Two months hence, at Salesforce’s gargantuan Dreamforce conference, which draws 170,000 people to San Francisco, Benioff will unveil the product he claims will steer the company to a new decade of growth. Its name: Salesforce Einstein, which explains the schmaltzy German—and the extravagant predictions. “If this is not the next big thing, I don’t know what is,” says the CEO of the world’s fourth-biggest enterprise software company.

Einstein, whose details are being revealed here for the first time, explains a lot of things. Why Benioff spent $390 million two years ago to acquire a hotshot young lieutenant, 35-year-old Steve Loughlin, and his responsive email and calendar product, and why Salesforce has gobbled up at least half a dozen Artificial Intelligence (AI) startups in the months since. Why the CEO of one of those acquisitions, MetaMind’s Richard Socher, a longtime Stanford academic specialising in AI, will now build the company’s first-ever pure research lab. And why after 17 years running Salesforce, Benioff can still get excited about his own products like a kid who’s found a new toy.

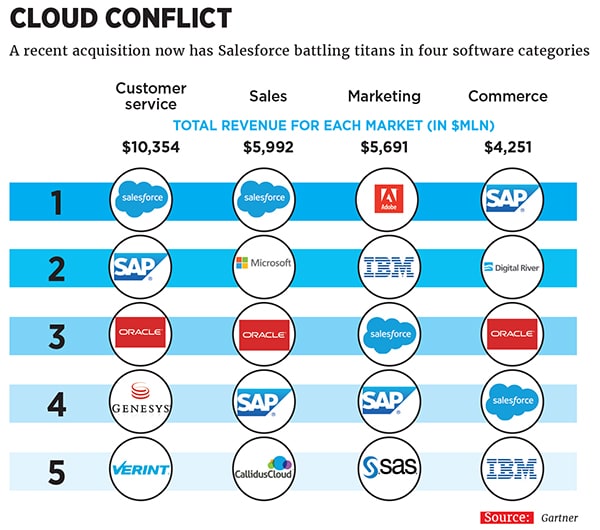

Benioff announces a big product or two every year at Dreamforce, but Einstein is something different. Einstein will integrate AI into almost all of Salesforce’s products, injecting predictive suggestion and insights into service, marketing and sales, as well as its newest efforts in collaboration and commerce. As such, Benioff tells his executives, Einstein won’t just slot in as another “cloud” for them to sell. Instead, Einstein will serve as a new nerve system across the entire business. “We are going to catch our competitors by surprise.”

Salesforce is hardly the first tech giant to bet big on AI. Google CEO Sundar Pichai is positioning his company for an “AI-first world,” while Microsoft has been wedding intelligence to business data for nearly 20 years. But bet against Benioff at your own risk. Since 2011, Forbes has ranked the most innovative companies in America—and every single year Salesforce has placed in the top two. Salesforce pioneered software as a service, ending the era of downloads and CD-ROMs. Benioff backed that up with successful bets on social media, marketing and mobile, establishing his company as a market leader in nine different product categories, reaching top positions in each of them—market positions dubbed “magic quadrants” by tech researcher Gartner when it plots those universes on graphs. Its products now interface with thousands of apps, touch many millions of business users around the world and bring in $8 billion in annual revenue. Salesforce’s consistent growth, combined with Benioff’s effusive salesmanship, has made it a longtime Wall Street darling, its $54 billion market cap outstripping net margins that have fluctuated between 2 percent and none at all.