How to beat Wall Street and Silicon Valley simultaneously

The American Dream is alive and well on Wall Street thanks to Robert Smith, the richest black person in America, who has figured out a way to re-engineer both private equity and enterprise software—and used this secret playbook to build a $4.4 billion fortune

Vista Equity billionaires Brian Sheth and Robert Smith: Their LBO-software mashup and its eye-popping returns are changing the game

Vista Equity billionaires Brian Sheth and Robert Smith: Their LBO-software mashup and its eye-popping returns are changing the game

Image: Tim Pannell for Forbes

It’s a Saturday afternoon, at the height of vacation season, in one of South Beach’s hottest hotels, and Robert Smith, the founder of Vista Equity Partners, is dressed like exactly no one within a 100-mile radius of Miami: In a three-piece suit. His signature outfit—today, it’s gray plaid, accented by an indigo tie and a pink paisley pocket square—apparently doesn’t take a day off, and Smith isn’t taking one now either. He’s gathered dozens of CEOs from his portfolio companies, software firms all, for a semiannual weekend offsite to drill them in the ways he expects his companies to operate.

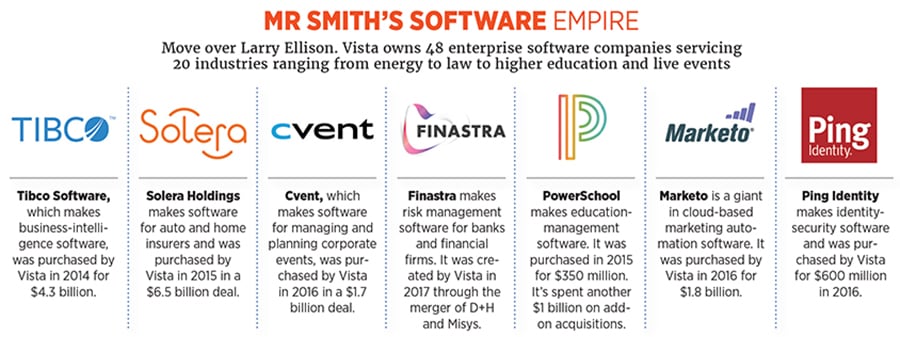

It’s not just the suit that’s unusual. Private equity firms almost never treat their portfolio companies, transactional chits by design, like an organic cohort. And until recently, PE, a field built on borrowing against cash-generating assets, wouldn’t touch software firms, which offer little that’s tangible to collateralise. Yet Smith has invested only in software over Vista’s 18-year history, as evidenced by the CEOs, like Andre Durand of the security-software maker Ping Identity and Hardeep Gulati of the education-management software company PowerSchool, who have been summoned to Miami Beach, waiting to swap insights about artificial intelligence and other pressing topics. And Smith deploys more than 100 full-time consultants to improve his companies.

“Nobody ever taught these guys the blocking and tackling of running a software company,” says Smith, as he takes a lunch break at South Beach’s 1 Hotel to nibble on a plant-based burger. “And we do it better than any other institution on the planet.”

Smith includes the likes of Oracle and Microsoft in that boast, and his numbers back up the braggadocio. Since the Austin-based firm’s inception in 2000, Vista’s private equity funds have returned 22 percent net of fees annually to limited partners, according to PitchBook data. Smith’s annual realised returns, which reflect exits, stand at a staggering 31 percent net. His funds have already made distributions of $14 billion, including $4 billion in the last year alone.

Not surprisingly given those numbers, Vista has become America’s fastest-growing private equity firm, managing $31 billion across a range of buyout, credit and hedge funds. Smith is putting all that money to work at a breakneck pace, with 204 software acquisitions since 2010, more than any tech company or financial firm in the world. After finishing an $11 billion fundraising for its latest flagship buyout fund last year, Smith has already deployed more than half of it, focusing as usual on business-to-business software. “They recognise it’s a kind of central nervous system,” says Michael Milken, whose bond-market innovations basically birthed the modern private equity industry and who has been a co-investor in two Vista deals. Taken together, Vista’s portfolio, with 55,000 employees and more than $15 billion in revenue, ranks as the fourth-largest enterprise software company in the world.

Smith deploys quickly for a simple reason: While the rest of private equity relies on identifying and rectifying inefficient companies, Vista bets that it can improve the operations of even well-run firms—and claims that it’s never lost money on a buyout transaction in its 18-year history.

Perpetual wins translate into mammoth personal gains. With an estimated net worth of $4.4 billion, Smith has now eclipsed Oprah Winfrey as the nation’s wealthiest black person. Vista has created another billionaire, Brian Sheth, the firm’s 42-year-old president and dealmaker extraordinaire, who has a fortune estimated at $2 billion.

Image: Jamie Mccarthy / Getty Images

Ever since Forbes outed Smith as a billionaire in 2015, there has been a steady stream of press about him, from the lowest-brow (tabloid interest in his marriage to a former Playboy playmate) to the highest (coverage of his philanthropy, including his Giving Pledge commitment and his stint as the chairman of Carnegie Hall). But neither Smith nor Sheth has ever before delved into Vista’s secret formula, which has many lessons for entrepreneurs, operators as well as financiers. “We do something no one else does,” Smith says.

On paper, Robert Smith’s journey was a textbook American success story: A fourth-generation Coloradan, he was the son of two PhDs who became Denver school principals and put education first at home. “Their father and I stressed the need for both of our sons to persevere once they identified and pursued a goal,” say Smith’s mother, Sylvia. “Robert understood that preparation, hard work and dedication were key to success in his classes.” In 1981, Smith headed to Cornell University to study chemical engineering, spending many nights and weekends in a three-person study group that met in the basement of the engineering school’s Olin Hall. During summers, Smith worked at Bell Labs back home in Denver—a college internship he landed as a high school student after persistent cold-calling.

After graduating from Cornell in 1985, Smith took engineering jobs, first at a Goodyear Tire & Rubber chemical plant outside Buffalo, New York, and later at Air Products & Chemicals in Allentown, Pennsylvania. In 1990, Smith moved to Kraft General Foods, where he focussed on coffee-machine technology. His efforts won him two patents: One for a stainless-steel filter and another for a brewing process that makes crema, the layer of foam on top of espresso. In 1992, Smith entered Columbia Business School. He was deftly acquiring the kinds of skills that would prove invaluable as the tech revolution exploded.

But Smith’s rise was also incredibly abnormal. Even today, as the 155th-richest person in America and the 480th in the world, he faces constant, if often unwitting, racism. At a recent dinner in New York City with a group of senior Wall Street types, including a high-level executive of an investment bank, Smith moved to pick up the cheque for dinner, but the senior banker stopped him. “I can’t have a black guy buy me dinner,” he chortled.

The sting of such incidents, whether offhand remarks or doors more overtly shut to him, had an effect on Smith. “It meant we had to work harder,” he says. “And that’s what we did.”

From his college days, when he joined the nation’s preeminent black fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, known for its bookish but professionally ambitious members like Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King Jr, Smith had support. A crucial mentor: John Utendahl, who founded a pioneering black-run investment bank and happened to speak at Smith’s Columbia graduation. Soon after, Utendahl, currently a vice chairman at Bank of America, took Smith to lunch and over tuna sandwiches persuaded him to ditch his MBA focus of marketing to work on Wall Street. “There is a spark, a poise, even a wisdom that you can’t teach or learn. Some people are just blessed to have it,” Utendahl says. “That’s how I felt when I met Robert as a young man.”

Smith landed in Goldman Sachs’ mergers-and-acquisitions department, eventually moving to San Francisco to advise companies like Microsoft and eBay and becoming cohead of enterprise systems and storage. He was part of the team that helped Apple recruit Steve Jobs back.

For all his prominent clients, it was a little-known Houston company specialising in software for auto dealerships, Universal Computer Systems, that caught Smith’s eye. Its margins were higher than any business Smith had advised, and he was stunned to learn the company’s owners were plowing its cash into certificates of deposits. Why not acquire other mature software companies, Smith asked, and apply their best business practices there too? Great advice, but the owners insisted that Smith roll up his sleeves and execute the plan for them. They backed up their offer with a commitment of $1 billion of the company’s cash, as the sole investor, if he started a private equity fund. “I had one of those in-the-mirror moments,” Smith says. “I looked at myself and asked, ‘If I don’t do this, how will I feel about it ten years from now?’ ”

The short answer: Regretful. And so, in 1999, Smith left Goldman and soon began recruiting co-founders, notably a business-school classmate, Stephen Davis, and a young analyst who worked under him at Goldman, Brian Sheth. The son of an Indian-immigrant father with experience in tech marketing and an Irish-Catholic mother who worked as a reinsurance analyst, Sheth would provide the yang to Smith’s yin, focusing on acquisitions and divestitures, so that his boss could concentrate on investors and the companies themselves. Their relationship would become ironclad: “When something is happening with our families we are each other’s first call,” says Sheth, who vacations with Smith and served as best man at his wedding.

When Smith quit, most of his colleagues thought he’d lost his mind. He was on a partnership track at Goldman, which meant he was set to receive a multimillion-dollar windfall given the firm’s impending initial public offering. What’s more, banks didn’t lend against software companies because they didn’t have hard assets. How could Smith run a leveraged-buyout business in software without leverage? The concentration risk also seemed huge—investing in a single industry where a few innovative lines of code from a competitor could make a business obsolete overnight.

But Smith saw things differently. Software was eating the world. Soon every company would become a software company, its business digitised. A portfolio of software companies serving 50 industries would be diversified with a stream of recurring revenue, given the shift to “software as a service”. Smith’s bet: Wall Street would soon realise that software companies not only gushed cash but actually had terrific assets to lend against—those ironclad maintenance contracts.

“Software contracts are better than first-lien debt,” Smith says. “You realise a company will not pay the interest on their first lien until after they pay their software maintenance or subscription fee. We get paid our money first. Who has the better credit? He can’t run his business without our software.”

In 2000, Smith opened Vista’s doors in San Francisco. His first acquisitions were all equity. As the firm went from one profitable deal to another, Smith eventually got lenders to finance Vista’s purchase of Applied Systems, an insurance software maker, in 2004, Vista’s first leveraged buyout. In 2007, Vista merged software companies serving utilities and created Ventyx, increasing the number of products it sold to existing customers substantially—a subsequent sale to ABB resulted in a profit of nearly $1 billion.

When the dust settled, Smith’s first buyout fund returned 29.2 percent annually net of fees. Smith raised money for a second fund from institutional investors, returning a net 27.7 percent annually. In 2011, seeking to escape the Silicon Valley bubble, Smith moved Vista’s headquarters to Austin, Texas. He could, by this point in his career, do pretty much anything he pleased.

“I still experience racism in my professional life,” Smith says. But by being smarter and working harder, Smith proved the American Dream extended to the finance industry, where he became the first self-made Wall Street billionaire who wasn’t a white male.

When Vista sells a company, Smith reverts to engineer mode, often giving its CEO an expensive Swiss or German watch. “It is not about being generous,” Smith says. “It is a function of the process and focusing on the detail of finding the person who is going to be the best at making that one gear.”

To Smith the watch represents that “we created a system”. And it’s that system that has allowed Vista to gobble up enterprise software companies, confident that it can almost always make them better. When Smith started shopping for software companies, he found that many were run by former programmers and other technologists who were not formally trained in business and grew rapidly by sheer strength of product launches, with little analysis of whether they made sense.

Smith’s rise was also incredibly abnormal. Even today, as the 155th-richest person in America, he faces constant, if often unwitting, racism

Drawing on his background as an engineer and a Goldman vet, Smith began writing what amounted to user manuals for running enterprise software companies. The manuals weren’t just about efficiency but also incorporated cost-cutting measures and fee-generating ideas. Eventually, Smith’s playbook became the Vista Standard Operating Procedures—VSOPs. These were later renamed a more generic and user-friendly Vista Best Practices.

“If you are a software executive, how do you build your commission structures or run your go-to-market strategy? How do you find and train talent? Who teaches you those things?” Smith asks.

To implement his playbook, Smith created an in-house McKinsey: Vista Consulting Group. These employees, now 100 strong, help portfolio companies implement the best practices, also 100 strong, most of which run three to ten pages, with reams of attachments and examples. Printed out, they fill binders. They are stored in a password-protected online library, available only to authorised portfolio company managers.

“I just had an employee get a promotion,” says Kristin Nimsger, CEO of Social Solutions, a cloud company providing data-management software for nonprofits like the United Way of Metro Chicago. “He was super-excited to get a log-in.”

The playbook includes exhaustive details on things like contract administration and steps needed to ensure a company is being paid for all the code or services its customers use. In one case, a company Vista bought charged customers only for inbound support calls, neglecting to charge a minimum amount for ongoing support. Vista cancelled all the contracts and got 100 percent of the customers to enter into new deals with higher minimum support payments.

Another set of playbook commandments revolve around sales, including incentives for salespeople cross-selling and upselling additional products. In one case, a portfolio company was rewarding salespeople the same way whether they brought in one-year contracts or longer-term ones.

In isolation, many of the playbook’s best practices seem mundane. But software companies are often rife with eccentricities and legacy processes endemic to startup culture. Things like weekly deal-pipeline meetings, commonplace at B-school-driven corporations like IBM and Procter & Gamble, are often absent. By sticking to the rules in Smith’s playbook, his software companies are transformed. Add some modest leverage, and, voilà, Vista got amazing returns.

Smith’s playbook is ever evolving, and Vista partners and portfolio companies are welcome to make suggestions. “One of the things I am most proud of is that we are going to add ten new best practices to the group,” says Reggie Aggarwal, the CEO of Cvent, a company that makes software for managing events and meetings.

Of course, critics argue that companies swallowed up by Vista are in no way immune to the traditional private equity slash and burn. Lawrence Coburn, CEO of Cvent competitor DoubleDutch, blasted Vista after the purchase, saying, “They eliminate duplication, slash R&D, optimize for financial performance and raise debt.”

Smith’s playbook goes well beyond corporate to-do lists. When Vista buys a company, all employees and recruits are required to take a personality-and-aptitude test, like one first developed by IBM. The hour-long test assesses technical and social skills, and attempts to gauge analytical and leadership potential. For Smith the test is particularly important because it attempts to bypass inherent biases, such as where people grew up or went to school, not to mention race or gender. Vista says 35 percent of the employees at its portfolio companies are women. Last year Vista companies administered 850,000 tests to hire 6,000.

“The meritocratic system creates loyalty,” Smith says. “People from all over the country from different places all take the test. We all know something about each other, that we came through this meritocratic system.”

The Vista test also identifies roles that fit personality profiles. A woman who ran a Domino’s Pizza franchise in North Carolina was deemed to be a good sales trainer and was promoted to do so for a Vista company. Another from the mailroom, for example, scored high on Vista’s test and became a programmer. “To write code you need to be creative,” Sheth says. “How much of that is going to happen if you all have the same background?”

After Vista has people where it wants them, there are boot camps that train employees, not just for two weeks but for six to nine months. In the past three years, Vista has put 12,000 new hires through these boot camps. They start by giving employees the big picture: How the Vista company makes money and the way customers use its products. The focus later shifts to specific corporate roles. Vista University provides “nanodegrees”, like one now being offered in artificial intelligence. Monthly meetings designed to cross-pollinate best practices among Vista employees from different companies in similar roles—from cybersecurity to HR and product development—are held.

All of this is run by Smith’s consulting group, which operates like a seasoned special-forces unit. “Financial performance of a company is just a trail in the sand of the operational performance,” Smith says. “The more standardised the input, the more standardised the output. You have to design your system, and you have to believe in it.”

With the rest of private equity getting turned on to enterprise software deals, Vista’s system is about to get a major test. While bargains are much harder to come by, Vista’s goals for each buyout will remain the same: Three times its money. Smith expects to hold on to his portfolio companies longer, identifying each acquisition target based on how much the Vista playbook can juice results. “We don’t underwrite to hope. We underwrite based on critical factors for success under our control,” Smith says. “What we need to change, we have changed before, so we know how to do it.” On average, Vista doubles the Ebitda of its companies within five years.

A lot of the responsibility will fall to Sheth, who has previously made a practice of racing to the exit door. For example, Vista bought Transfirst, a payments-processing software maker, for $1.5 billion in 2014, then sold it for $2.35 billion in just over a year, tripling Vista’s money once leverage was factored in. In January, Vista sold its majority stake in Trintech, which makes software for financial professionals, after it doubled revenues in two years. On an average, Vista’s exits tend to occur 4.7 years after purchase, compared with 5.7 for Blackstone.

While it would be easy enough for Smith to fall back on philanthropy—recent pledges include $20 million to the new National Museum of African American History & Culture and $50 million from a foundation linked to Vista’s first fund to help Cornell boost the representation of women and minorities in scientific research—numbers like that keep Smith feeling upbeat, even cocky. Nearly two years ago, at the Milken Institute’s annual Global Conference, Smith found himself shoulder-to-shoulder onstage with the old-guard billionaires of the buyout business, including David Rubenstein, Leon Black and Jonathan Nelson.

When Rubenstein said his investors had been conditioned to accept lower returns given the high price of assets, Smith shifted in his chair and parried, “I got to go get some of his [investors].” He then turned to Rubenstein and, with the brio of someone who knows he’s arrived, quipped: “Let me know where you are flying next. I will go with you.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)