GVK's Big Australian Bet

GVK has to raise $7 billion in debt to succeed in its venture to mine coal Down Under and fight off stiff competition

The Great Barrier Reef, off the coast of Queensland, is one of Australia’s greatest natural gifts. The coral reef system stretches for 2,600 km and can be seen from outer space.

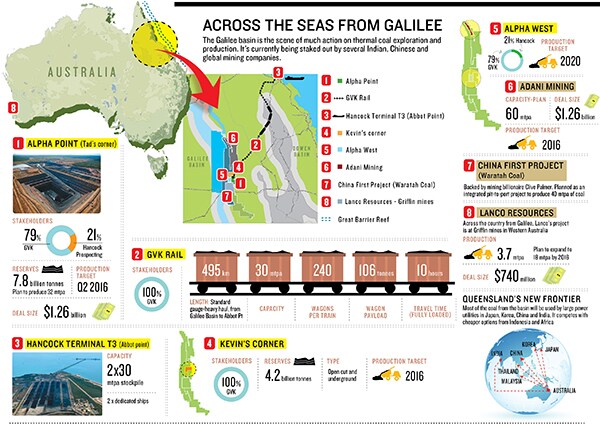

But, head inland into Queensland and into the outback and the contrast cannot get sharper: Giant excavators, three stories high and weighing hundreds of tonnes, work at mines of Brobdingnagian proportions. The newest of these basins is Galilee. The prize here is millions of tonnes of quality thermal coal, and a bunch of aggressive miners from India and China are staking multi-billion dollar bets to snag it.

Leading the charge across three of the mega-mines in the basin is an unlikely Indian entrepreneur, who’s a newbie in the mining business. GV Sanjay Reddy, vice chairman of the GVK Group, first went to Australia looking for fuel for his power project in India. He switched tracks when he saw an opportunity in the huge, unconstrained mines available there.

By late 2011, he paid Hancock Prospecting, one of Australia’s biggest resource companies, $1.3 billion for Alpha, Kevin’s Corner and Alpha West. His plan is to transform GVK from a middling Indian infrastructure player, struggling with debt and cash flow problems, to a mining major by 2025, which will produce 84 million tonnes of coal a year. To put the number in perspective, India’s total thermal coal imports in 2012 were about 100 mt.

Reddy did what few entrepreneurs as leveraged as him would do (GVK’s long-term borrowings were Rs 11,094 crore in FY2012): He announced he would find $10 billion, to fund the coal extraction, build rail lines and a port terminal needed to carry the coal to energy-hungry utilities in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China.

But the past 15 months—since the deal was signed—have been tough. The economic environment got worse, coal prices fell from a peak of $120/tonne to about $90, funding dried up, and Reddy was unable to complete the financial closure as planned. There aren’t too many people who have the courage to back Reddy’s audacious bet.

Right now, he needs to raise debt of about $7 billion to achieve financial closure—and he doesn’t have much time. The clock has begun ticking on the $1 billion borrowed for the mine acquisition. Competition is keeping up the pressure as well. Right next door is Gautam Adani, who had actually reached Galilee before Reddy, and planted his flag at the Carmichael River. AMCI-Bandanna, a joint venture between a coal exploration company and a private equity firm, is the closest in terms of clearances. Among his most vociferous rivals is Aussie mining tycoon Clive Palmer, promoter of China First (Waratah coal).

As of now, GVK has a lead over the others. Galilee is about 500 km from the sea. With environmental clearances in place, Reddy’s integrated pit-to-port project is best placed to carry the coal to the markets.

Both Adani and Palmer have been trying, so far in vain, to get exclusive rail and port linkages. The Queensland government declared the Alpha mine, a ‘project of state significance’, which makes land acquisition easier. Except the mining lease, most approvals are in place and land deals have been locked in with stakeholders.

But with every day of delay, Reddy’s first-mover advantage could get whittled. And the prospect of more capacity coming on stream makes it tougher for him to sign long-term deals with buyers.

Analysts have also criticised the way in which Reddy has structured his Australian venture. Ninety percent of the project is owned by the GVK family, and not the listed Indian company GVK Power and Infra (GVKPIL). However, half the risk (debt of about $1 billion) is on GVKPIL’s books. This leads to an unfavourable risk-reward to minority investors, says BNP Paribas analyst Vishal Sharma, in his reports on GVK.

So, the only way that Reddy can prove his critics wrong is by pulling off his audacious gamble. But, can he?

Georgina on my side

“Doing business Down Under is, in many ways, easier than in India,” says Reddy. Australians tend to speak their mind and what you see is what you get, he says.

The Alpha mine project is top priority for the group. Reddy has travelled to Australia 27 times in the past 24 months. “It was not possible to leave it to anyone else at this stage,” he says.

For much of 2012 it was impossible to get investors interested in the Alpha project for another reason: In May, the federal government in Canberra ‘stopped the clock’ on environmental clearance for the project, after the Queensland government cleared it. When environment minister Tony Burke said the project was ‘shambolic’, quite a few hearts at GVK Hancock almost stopped beating. The federal agency SEWPaC (Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities) wanted more details on the environmental impact of the mine and the Abbot Point port on the Great Barrier Reef.

Greenpeace ratcheted up protests by addressing banks, potential investors and the stock markets. In a strongly worded ad in Indian newspapers, it warned investors of environmental damage the GVK project could cause. Environmentalists were not the only voices against the project. Unesco, in a report in June, said the reef could be listed as a world heritage site in danger if the government continued with “threatening industrial development” along the Queensland coastline.

Rival miner Clive Palmer has been a vociferous critic. He sued the Queensland government when it granted priority rights to the GVK rail link. More recently, when the Indian group laid off some employees, he was on record to say the GVK job cuts have left the Queensland government with egg on its face over “their policy of favouring Indian companies”.

But mining industry insiders say GVK is lucky to have one of the toughest Aussie voices on its side: Gina Rinehart, owner of Hancock and the world’s richest woman on the Forbes global billionaire’s list. Rinehart is one of Australia’s biggest climate sceptics, a vociferous opponent of carbon taxes, and has lobbied for allowing foreign labour in Australian mining.

The reticent heiress has developed a great relationship with the Reddy family and has made at least six trips to India last year. Her iron-ore projects in Western Australia are in early development stage, and there is a lot of cross synergies between the two projects, particularly on dealing with prickly issues, say senior GVK executives.

Rinehart, worth $18 billion, made her fortune in the super-boom that resources have enjoyed in the past five years, and is now focussed on iron ore. Hancock is developing the gigantic Roy Hill mines. She recently roped in Marubeni, China Steel and Posco as strategic partners taking up 30 percent of the multi-billion dollar project.

Reddy might well learn from Reinhart’s strategy and rope in a strategic investor. GVK now has 79 percent and Hancock 21 percent in Alpha. Reddy may be looking to reduce his stake to 51 percent soon, by selling equity to new investors. Sources in the banking industry say he may be very close to roping in a large Asian coal consumer as an equity investor.

Reinventing the Rules

Reddy’s biggest challenge is to overhaul the bloated cost structure that has made Australia among the most expensive places to mine in. James O’Connell, managing editor of Platts International Coal Report, says production costs are about $70/tonne. This worked when coal prices were high, but led to huge pressure when prices fell.

Customers are turning to cheaper supplies from Indonesia and elsewhere. “Miners’ pay could range from A$300,000 to A$400,000 a year. Contracts with the rail networks are $8 to $10 per tonne, and treatment charges for environmentally sensitive buyers in Japan add to costs,” says O’Connell. Within Australia, as production gets unviable, BHP Billiton-Mitsubishi has mothballed projects at Norwich Park and Red Hill, and Rio Tinto has shut its Blair Athol mine.

Trying to turn his inexperience into an advantage, Reddy is now questioning every convention and every assumption of Australian miners.

For starters, he has set a clear target: His team has to aim for a price of $50/tonne (freight on board). This would immediately bring Alpha coal within the first quartile of the cash-cost curve of global coal producers.

Reddy hired McKinsey to help bring in best practices from around the world. This meant attacking the cost culture within the Australian mining industry. For instance, local miners follow the open book alliance method of contracting, whereby costs and the margins are remunerable, and the project is invoiced based on actual costs incurred plus margins. This often leads to ‘cost blowouts’. Reddy’s team wanted contractors to bear these risks, and all major contracts would be based on fixed time, fixed cost EPC (equipment procurement and construction).

When GVK began negotiations to find partners, the 60 million tonne port terminal was expected to cost $2.6 billion. GVK signed up Korean giant Samsung C&T and Brisbane-based Smithbridge for a three-way joint venture. Samsung agreed to complete the project at a maximum cost of $1.8 billion in 36 months. The EPC contract is expected to be signed by April.

“The kind of equipment you order can make all the difference,” he says. His communication to the Australian team, led by group managing director and CEO Paul Mulder, is clear: “‘Good enough’ is what you need, not ‘best available in the world’.”

One example of this is using, the more efficient Draglines—huge excavators (they cost $50 million to $100 million each) used in open-pit mining—instead of smaller bucket-wheel and other extractors. The result: Costs reduced by 20 percent.

Bringing the Australians around to GVK’s way of working was a gradual process, says Reddy. The venture is run with little intervention from India (most of the project team is Australian), but aligning their thinking was essential, he says.

One advantage of the economic slowdown was the reduction in mining activity that made equipment makers like Caterpillar and Hitachi offer better deals. Vendor financing will be an important source of funds, since equipment costs for Alpha will run into millions of dollars.

Reddy also hopes to reap the benefits of scale. The Alpha chain will be controlled from a Joint control centre, with teams from the mine, railroad and port sitting in a single place to optimise results. Australia’s best coal comes from Hunter Valley in New South Wales, but supplies from there often hit bottlenecks at the port. GVK’s railroad and port will be open to other customers and will be standalone profit centres.

But not everyone is confident that clipping costs will help the project sail through. Debasish Mishra, senior director at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, says GVK’s success in Alpha depends largely on the international coal demand-supply scenario and prices. “A variety of factors may keep coal prices in check. Japan is slowly re-starting its nuclear reactors, the Chinese economy is still not out of the woods and there will be a huge coal surplus in the US because of shale gas,” he says. Dampened prices will have an impact on investors’ appetite for new projects like Alpha, he says.

Image: Patrick Hamilton Photograhy

The Abbot Point port can be used by other customers and serve as a standalone profit centre

Supplying to North Asia

Reddy believes the solution to many of these problems lies with the coal-guzzling markets of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and spent much of 2012 meeting coal users, traders and bankers from the region. There are two objectives: To find customers willing to sign long-term contracts for coal from Galilee; and rope in a couple of large buyers as strategic investors, says Mudit Parashar, senior vice president corporate development, who works closely with Reddy.

In all probability, much of the debt for the project will also be raised from lenders in north Asia. Negotiations are on with Chinese and Japanese banks, export credit agencies and equipment manufacturers, he says.

Boao Forum for Asia (BFA) is a high-level forum modelled after the World Economic Forum and hosts meetings for heads of states and business people. In November, GVK sponsored the BFA Asia Financial Co-operation Conference in Mumbai, attended by the who’s who of the Asian financial fraternity.

“A solid investor can make the project much more bankable,” says Prasad Patkar, portfolio manager, Platypus Asset Management in Sydney. But the question is, at what price? As of now it seems Rinehart sold well, as the super-cycle of coal prices has cooled off and prices have come off by over 30 percent, he says.

Reddy says it is silly to look at such a project with “today’s eyeglass”; you have to look at it for the long term. He admits it was touch-and-go till recently. But with environmental clearances in place, it is only a question of taking key strategic calls, he says. Over the next 50 years, the opportunity is enormous in a country with very low political risks.

“Alpha coal is now our calling card,” says Parashar. Till recently, the Galilee basin coal was unknown to consumers and its quality untested.

Hancock had spent $80 million on a test-pit to mine 125,000 tonnes. The coal was sent to potential customers in China and South Korea, to prove its quality and design the most efficient system. Alpha coal is priced at 6 percent off the benchmark price of thermal coal exports from Newcastle in Australia.

Right now, the project has been clearly defined and all systems are geared to award the contracts and sign the final land deals. The Great Barrier for Reddy is finance. If that deal fructifies, the scuba diver who has enjoyed many a great dive in the big reef, will get a real shot at proving both the environmentalists and the money men wrong.

Correction: This article has been updated for corrections from the version that appeared in the print magazine.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)