Eddie Brown: One of Wall Street's greatest untold stories

Eddie Brown grew up as a labourer in the Jim Crow South. What he's accomplished since has left quite a legacy

Brown Capital founder Eddie Brown in the company’s boardroom. He learnt entrepreneurship from his uncle, a moonshiner, who taught him to drive at the age of six

Brown Capital founder Eddie Brown in the company’s boardroom. He learnt entrepreneurship from his uncle, a moonshiner, who taught him to drive at the age of sixImage: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

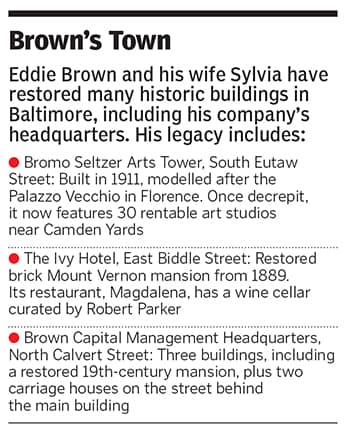

Inside a four-storey, sumptuously restored 19th-century town house in Baltimore, three of Wall Street’s best stock pickers are roasting each other in a wood-panelled boardroom.

“Usually when we’re getting rid of something [in the portfolio], we’re getting rid of Kempton’s mistakes,” booms Keith Lee with a laugh, referring to Kempton Ingersol, a Brown Capital Management portfolio manager and the son-in-law of the firm’s CEO and founder, Eddie Brown.

Lee, 59, is the president of $12 billion (assets) Brown Capital and leader of a team of portfolio managers that Morningstar has put in its hall of fame.

Brown Capital is an old-school stock-picking operation that doesn’t chase the latest fads on Wall Street. The firm hunts for unglamorous but fast-growing companies. Brown mostly buys growth companies that have revenues of less than $250 million. So far this year, Brown’s flagship Small Company Fund is up by 21 percent, trouncing the market, and has averaged a 19 percent return annually over the past decade. Since its inception in 1992, the fund is up 22-fold.

“We take what we do extremely seriously,” says Lee, who started at the firm 28 years ago. “We just try not to take ourselves that seriously.”

The firm’s informal culture and its commitment to championing unloved growth stocks is in many ways a reflection of the incredible life journey of Eddie Brown, one of the great untold stories of African American success on Wall Street.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)