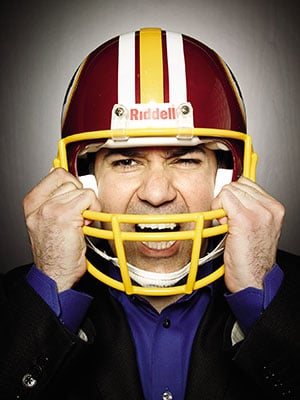

DMI: Cashing In On The 'Bring Your Own Device' Trend

Sunny Bajaj turned the mundane job of managing a mobile workforce into a raucous success

Leaning over a high-backed chair toward the phone in his corner office, DMI Inc CEO Jay Sunny Bajaj is calling Irish cement company James Hardie Industries for the first time. It’s a $1.5 billion (sales) firm that uses 1,700 mobile devices, all managed by DMI, a contract Bajaj has won against AT&T. The customer tells Bajaj that, unlike the telco’s half-promises, DMI’s manager makes him feel like she’s “sitting right there”. Bajaj, who can’t sit down himself after hurting his back on a client visit two days before, flashes a grin. “If they weren’t happy, I’d be on a plane right now.”

DMI (short for Digital Management Inc) is a jack-of-all-trades service shop for companies migrating toward a mobile workforce (ie, all companies). The big trend in IT is BYOD, or ‘bring your own device’, in which employees are allowed or forced to use their personal iPhone or Android at work. But the devices have to be locked down for corporate use. This has created a gold rush among service and software companies that handle activations, software updates, security, app development and support.

Bajaj, 37, started DMI 12 years ago with a desk, a computer and $25,000 from friends and family. It helped that his father, Ken Bajaj, is a major player in Beltway tech circles, having sold his software and advisory firm AppNet to Commerce One for $2.1 billion back in 2000. But the son has moved out of the father’s shadow. DMI now has 1,800 employees in seven offices and contracts with all 15 cabinet-level departments of the US government and corporate customers such as Toyota, Pfizer and the Royal Bank of Scotland. DMI recently built a cocktail app for Bacardi and a World Cup app for Anheuser-Busch InBev. “One of my team was in a huge retail chain the other day wearing their DMI lanyard,” Bajaj says. “The floor manager said, ‘I know DMI— you manage our mobile devices.’”

DMI has far bigger rivals all around it. Telcos and BlackBerry bid against it for device management deals, a market worth $1.6 billion this year, according to Gartner. In app development DMI goes up against Pivotal Labs and AKQA. And it battles Accenture, Hewlett-Packard and Deloitte for consulting deals.

But DMI’s 100 percent annual growth over the last five years is faster than nearly all of them, thanks to acquisitions and a raucous atmosphere Bajaj has created around himself. DMI sells at least six different services, and Bajaj trains his staff to get in the door by offering to manage a firm’s smartphones and tablets or build its apps, and then look for openings to handle security, strategy and support. A sports nut, Bajaj serves as part coach, part cheerleader for his staff. Office rooms bear names like “the End Zone”, and company bonding often involves events such as an all-hands Top Chef-themed grill competition on the office patio. He has been known to end a big afternoon client meeting with a shot of tequila. Bajaj loves the stuff, with DMI-branded shot glasses and even a conveyor belt to pass them out at the annual company bash. He’s close to finalising a private-label DMI brand of tequila that he wants made before he’s a public company CEO. “I drank tequila with [partners] Samsung, with Good Technology. It’s boring if you’re always talking business. You can be serious but have a little fun. And no one turns it down.”

Bajaj is always smiling, always selling. In his back-injuring trip to New York he met with the CIO at an investment bank where they started out discussing the bank’s phones and tablets but quickly got to talking about its need for new employee apps. And how DMI could deploy them. And test them. And why not maintain them, too? “Eventually the CIO has four or five ways to work with us in his mind, and they want to take the conversation to giving us all of it,” Bajaj says. “I do mobile apps for Novartis for $1.5 million a year. That could be a $10 million account.”

The founder could someday become a billionaire if an IPO goes off in early 2015 as planned—or a buyer comes along before that. The privately held firm has rejected a $600 million offer, and Bajaj owns more than 65 percent. DMI has been cash-flow positive since 2008 and will gross about $350 million this year, up from about $100 million in 2011. That’s more than the device management firms acquired by IBM and Google, and even more than the revenue at AirWatch, for which VMWare paid $1.5 billion in January at roughly 15 times revenue. DMI would fetch a slightly lower multiple because of its lower-margin government and services-related work.

Bajaj’s tale is far from a rags-to-riches story. Both his parents started and sold tech companies valued in the hundreds of millions. Born in Detroit and of Indian heritage, Bajaj grew up not far from DMI and got his first job in Mom’s mail room at 12. After a brief try at investment banking Bajaj joined his father’s company to learn the tech services trade.

In 2002 he decided to break out on his own, eyeing the complacency of government tech contracts. But he struggled to get his foot in the door. Selling PC hardware made him some cash that first year; Bajaj then tried his hand at “staff augmentation”, matching techies to growing contractors.

Bajaj broke through as a contractor himself when he scored a $40,000 job to document the Small Business Administration’s standard operating procedures in 2004. But to score bigger contracts DMI had to seem bigger, too. That meant filling his office with family and friends on mornings when prospective clients were visiting. On some pitches he would bring a knowledgeable friend along as a pretend employee, right down to the business cards printed that morning at Kinko’s. “Every small company does stuff like that,” he says.

By 2004 DMI was winning seven-figure contracts from big agencies, but the 2008 recession and new competition were driving margins down, and Bajaj decided they weren’t coming back. He started diversifying in 2010, investing $25 million to build a commercial practice, which is now 40 percent of sales and growing. Much of DMI’s growth has come through five acquisitions, such as Golden Gekko, an app developer in Barcelona, and the Pappas Group, a marketing agency that built the website for the NFL Players Association.

Bajaj claims he gets regular investment or buyout offers. He says if he sells, it has to be for more than $2.1 billion—the price at which his father, who now serves as DMI’s COO, sold AppNet years ago. Dad’s eyes twinkle when he hears this. “He wants to show he’s better than me,” he says. “But this business is all about people, and Sunny’s a far better people person than I ever was.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)