Cyanogen giving Apple, Google a run for their money

A brazen startup has a very real shot at busting up the world's smartphone duopoly

It’s a little hard to take Kirt McMaster seriously at first. He tends to run on his own schedule, and when he shows up 20 minutes late for a meeting on a recent weekday, there’s not so much as a mention of his tardiness, let alone an apology. In black jeans, a black hoodie that looks a half-size too small, brown Birkenstock sandals and a pair of fat black rings—one on his left thumb, one on his right pinkie—the 46-year-old looks more like a techno beach bum than an entrepreneur. He works out of a squat, grey, converted plumbing-supply store in Palo Alto, California, that doesn’t call attention to the fact that his startup, Cyanogen, is housed inside. The period sign on the façade says ‘John F Dahl Plumbing and Heating (since 1895)’. The wardrobe and the location are disguises, necessary when one is hatching one of the most daring plots in Silicon Valley history. But McMaster happily blows his cover minutes into our conversation, summing up his mission—preposterous as it sounds—in his booming baritone: “We’re putting a bullet through Google’s head.”

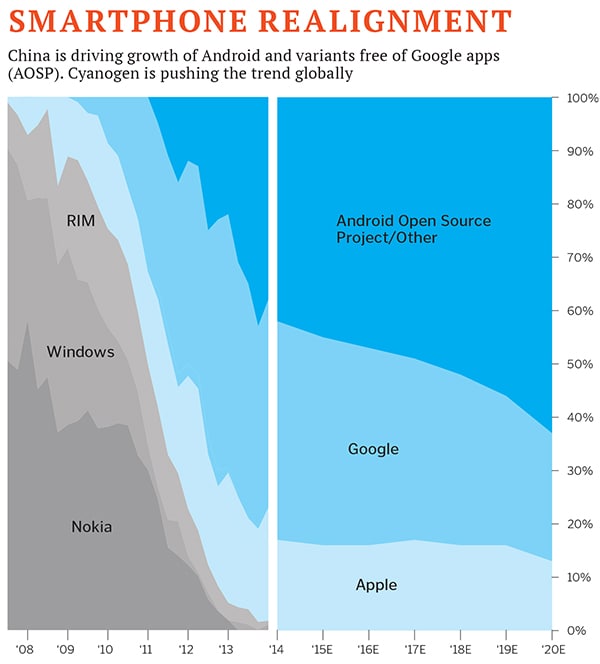

The time is ripe for someone to try. The mobile revolution kicked into gear by the iPhone is getting stagnant just as it’s reaching a new inflection point. The number of smartphones on the planet is expected to grow from about 2.5 billion to nearly six billion by 2020. Prices for fast and feature-rich mobiles are crashing, allowing new powerhouses like Xiaomi to emerge in record time. Yet Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android control 96 percent of the mobile operating system market. It’s their chess game, and we all get to choose between white and black. McMaster doesn’t so much want to insert himself between Apple and Google as to kick their chessboard over and deliver to the world a third option, Cyanogen, a six-year-old mobile operating system that’s essentially a souped-up version of Android and available outside of Google’s control.

McMaster, who revealed his plans in detail for the first time in a series of interviews with Forbes, is amassing a war chest and powerful allies to go to battle. Cyanogen just raised $80 million from investors that include Twitter, mobile chip powerhouse Qualcomm, carrier Telefónica and media titan Rupert Murdoch. The round, which values Cyanogen at close to $1 billion, is being led by PremjiInvest, the investment arm of Wipro’s billionaire founder, Azim Premji, India’s third-richest man. Earlier investors pumped an additional $30 million into Cyanogen, among them: Benchmark, Andreessen Horowitz, Redpoint Ventures and Tencent. Microsoft, which considered investing in Cyanogen, is not participating in the current round, according to people familiar with its decision. But, these people say, Microsoft and Cyanogen are close to finalising a wide-ranging partnership to incorporate several of Microsoft’s mobile services, including Bing, the voice-powered Cortana digital assistant, the OneDrive cloud-storage system, Skype and Outlook, into Cyanogen’s devices. The companies refused to comment, but at least one smartphone maker said his company was planning to sell a Cyanogen phone with many of those services built in later this year.

“App and chip vendors are very worried about Google controlling the entire experience,” says Peter Levine, partner with Andreessen Horowitz. That’s particularly true for firms that compete with Apple or Google, among them Box and Dropbox in cloud storage; Spotify in music; Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Snapchat in messaging; Amazon in commerce; and Microsoft in a wide swath of sectors. The lessons from the PC era, when Microsoft used its Windows monopoly to sideline rivals and dictate terms to PC makers, still resonate. A third choice would be welcome and unleash a new wave of mobile innovation.

Cyanogen has a chance to snag as many as one billion handsets, more than the total number of iPhones sold to date, according to some analysts. Fifty million people already run Cyanogen on their phones, the company says. Most went through the hours-long process of erasing an Android phone and rebooting it with Cyanogen. McMaster is now persuading a growing list of phone manufacturers to make devices with Cyanogen built in, rather than Google’s Android. Their phones are selling out in record time. Analysts say each phone could bring Cyanogen a minimum of $10 in revenue and perhaps much more.

Of course, far more powerful players have tried and failed to establish a third mobile OS in the last several years: Microsoft, BlackBerry, Samsung, Mozilla, Nokia, Intel, Palm. McMaster is well aware of this history, which is why, he says, co-opting Android is the only way down the path. Then, by opening up Cyanogen’s code in ways that neither iOS nor Android have done, McMaster is hoping to attract app developers who feel hemmed in by Apple and Google. A company like Visa or PayPal would be able to build a contactless payment system that works just as well or better than Google Wallet. Skype could be built into the phone dialler. A service like Spotify could become the default music player on a phone. “In a perfect world, the OS should know I use Spotify for music,” McMaster says. “I should be able to talk to the phone and say ‘Play that song’ and the f*%&ing song plays with Spotify. It doesn’t do that today.”

Cyanogen was born long before McMaster anointed himself the David to Google’s Goliath. It dates back to 2009, when Steve Kondik, a 40-year-old entrepreneur and veteran programmer, began tinkering with Android in his Pittsburgh home during late-night hacking sessions. (Android is open source, so anyone can download the code and tweak it. As long as people don’t break things, Android apps, including Google’s own—Gmail, Maps, Drive, the Play Store and others—will run without problems. And Google, which gives away Android, makes money from ads in the apps and collects data from handsets.) An engineer who taught himself to code at the age of eight, Kondik has a greying, receding hairline. He is as understated and measured as McMaster is brash and impulsive. Kondik began by making some changes to the Android user interface, then worked on improving performance and extending battery life. Pretty soon, hundreds of developers coalesced around him and began contributing their coding skills to the Cyanogen endeavour, then called CyanogenMod. “It was completely unexpected,” Kondik says. “There was no grand vision.”

Online forums started buzzing about Kondik’s highly customisable version of Android, and by October 2011, a million people had installed Cyanogen on their phones. Eight months later, it was five million. Eventually Samsung took notice and hired Kondik to join a research and development team in Seattle. The company gave him permission to continue with his off-hours hacking of Android. “It very quickly took over my life,” says Kondik, who remains in Seattle, where most of Cyanogen’s engineers work. (The company has fewer than 90 employees but receives contributions from as many as 9,000 open source programmers.)

While Kondik was hacking with his band of programmers, McMas- ter was bouncing around various tech firms. A Canadian who grew up in Nova Scotia and dropped out of college, he joined a Silicon Valley startup during the dot-com boom and later moved to southern California, where he worked at a handful of digital marketing agencies. He then helped run Boost Mobile, a pre-paid wireless service that originated in Australia and is now owned by Sprint. McMaster later went to work at Sony, helping to plot mobile strategies. Like many techies, McMaster was an early iPhone user. But as he brainstormed business ideas, he grew increasingly intrigued with Android’s openness. In 2012, he bought a Samsung Galaxy 3, the first Android phone he felt was on par with the iPhone, but he immediately grew frustrated that the latest Android version—known as Jelly Bean—was not available for it. So McMaster wiped his Galaxy clean and installed CyanogenMod, which, thanks to its army of programmers, had already incorporated the Jelly Bean update. This, McMaster says, led to an epiphany of sorts while he was working out at a gym in Venice, California. If you could flash a device with an open operating system, you could customise it as much as you wanted. “It means you can do whatever you want with the device,” McMaster says.

That evening, he found Kondik through LinkedIn, and the two got on the phone. McMaster did most of the talking, pitching Kondik on a plan to turn his open source project into a company. “I’ll be CEO; you’ll be CTO. I’ll get some money. Let’s go,” McMaster remembers saying. Kondik invited McMaster to Seattle, and the two met the next day at a brew pub where Mc- Master’s unfiltered enthusiasm and Kondik’s caution collided. “I was really sceptical at first,” Kondik says. Still, within 48 hours, the pair had agreed to team up, and Cyanogen, the open source project, spawned Cyanogen, the company. While some long-time Cyanogen community members howled at the notion that their project was going corporate, McMaster brushes off their concerns with a wave of the hand. (A third co-founder, Koushik Dutta, left the company in 2014.)

McMaster and Kondik got a chilly reception at first from the moneymen of Sand Hill Road. The reaction of Andreessen Horowitz’s Levine was typical. “I didn’t believe a startup could come in and create a new OS,” says Levine, who went on to invest in Cyanogen’s second round and kicks himself for passing on the first. Others were put off by McMaster’s braggadocio. But in Benchmark partner Mitch Lasky the duo found a receptive ear. The fact that millions of people had taken the trouble to install Cyanogen showed that demand was real, Lasky says. “There are a couple of billion potential Android handsets in the world. Even a small percentage of them is a massive market,” Lasky says.

How far Cyanogen has evolved from hobbyist Tinkertoy to mainstream smartphone OS is on display inside Joseph Reid’s Toyota Prius, which he drives around San Francisco. Like many fellow drivers for the Lyft on-demand car service, Reid gets his customers and directions through a smartphone mounted on his dashboard. His is a head-turner: Thin and elegant, with a striking 5.5-inch screen. It’s a Chinese-made OnePlus One, a Cyanogen phone released last year that Gizmodo called an “unbelievably fantastic smartphone”. The device outperforms many of its competitors, including, in various tests, the iPhone 6. It starts at $300, without a subsidy. Google’s Nexus 6, which has similar specs and is considered the top of the line for Android, costs twice as much. The OnePlus One is Reid’s second Cyanogen phone. He got hooked on the software a year earlier after he bought a Samsung Galaxy S4. Reid didn’t care for the apps that Samsung and Sprint had put on it, and the overall experience fell short of his expectations. So Reid installed Cyanogen. “People remarked how fast it was,” he says. The OnePlus One is even faster. The company has sold close to one million to date.

McMaster and his crew are busy courting other phone-makers. Last year, Micromax, the market leader in India, began selling Cyanogen phones under its high-end Yu brand. (The deal, which made Micromax the exclusive Cyanogen seller in India, led to something of a falling-out between Cyanogen and OnePlus.) The company has released the phones in batches through its online store; they sell out within seconds. “People are lapping it up,” says Rahul Sharma, CEO of Micromax. “Every week, we are ramping up production.” Sharma says he chose Cyanogen to meet customers’ demand for phones they can personalise. In many ways, Micromax is following in the footsteps of Xiaomi, the $46 billion Chinese behemoth, which built a buzzy brand and a loyal following by creating highly customisable phones. But rather than hire an army of programmers to develop the software, as Xiaomi did, Micromax has outsourced the task to Cyanogen. Other brands in emerging markets are sure to jump on the same bandwagon, says Asymco’s Horace Dediu, an influential industry analyst. “Cyanogen is now an enabler for the next Xiaomis.”

There are likely to be many of them. In March, Alcatel, the number seven mobile phone-maker in the world, said it will bring to the US its 6-inch Hero 2+ running Cyanogen, for $299. Meanwhile, mobile chip-set powerhouse Qualcomm said it will build Cyanogen into its “reference design”, a sort of technical template that smaller phone-makers the world over use to create phones under their own brands. The first true expression of McMaster’s vision should come later this year in a phone being made by Blu. The Miami company has become one of the most popular phone-makers in Latin America; its phones are sold in the US through Walmart and Best Buy and are among the best-selling unlocked phones on Amazon. Blu says it will launch the first Cyanogen phone that will be stripped of Google’s suite of mobile apps. While Samuel Ohev-Zion, Blu’s CEO, says all the details have not yet been worked out, he envisions a phone that will use Amazon’s app store, the Opera Web browser, Nokia Here for maps, Dropbox and Microsoft’s OneDrive for cloud storage and Spotify for music. It would also have Bing for search and Microsoft’s Cortana as a replacement for Google’s voice assistant. “When these other apps are deeply integrated into the phone, most of the time they perform better than the Google apps,” says Ohev-Zion. Phones like these are how Cyanogen will make its real money. Today the company earns minimal revenue, selling “themes” that users can apply to customise the look and feel of their phones. (It currently relies on the Google Play Store for billing, but over time plans to build its own store.) The bigger opportunity will be from revenue-sharing deals with app developers who integrate their services deeply into Cyanogen-based phones. The deals will take many forms, from distribution to in-app purchase agreements to customised services for specific countries, says Vikram Natarajan, who runs business development for Cyanogen. In some cases, the company will share the revenue from those deals with phone-makers that are struggling with narrow margins. “We will give them revenue over the lifetime of the handset that they never had before,” Natarajan says.

Despite McMaster’s belligerent tone, Cyanogen can succeed with- out doing real damage to Google, which declined to comment. During an onstage interview at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, Sundar Pichai, the company’s head of products, who oversees Android, said he’s unsure what Cyanogen’s selling point is. He also noted that Google’s services are very popular and questioned the viability of phones that don’t include them.

More likely, Cyanogen’s success would amount to a huge lost opportunity for Android and hem in the company between Apple at the high end and Cyanogen elsewhere, complicating Google’s prospects at a time when investors are worried that Google will never make as much money in mobile as it did on the desktop. Still, even some Cyanogen allies are not fans of the taking-down-Google talk. “Kirt’s aggressive and has a lot of bravado, and I don’t think the company would exist without it,” says Sandesh Patnam, of PremjiInvest. “I wish he didn’t poke the bear too many times and so loudly.” That said, McMaster’s open swipes at Google may have ancillary benefits beyond generating headlines: They make Cyanogen visible enough that Google, which operates under the glare of anti-trust regulators, may think twice before doing anything that could be construed as undermining a potential rival. It’s also what charges up McMaster. “As with any great myth, you need a common enemy,” he says. “Right now, Google is the common enemy.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)