Cleveland's Invention Machine

John Nottingham and John Spirk are the most successful inventors you've never heard of, with a can't-lose business model that would make Edison blush

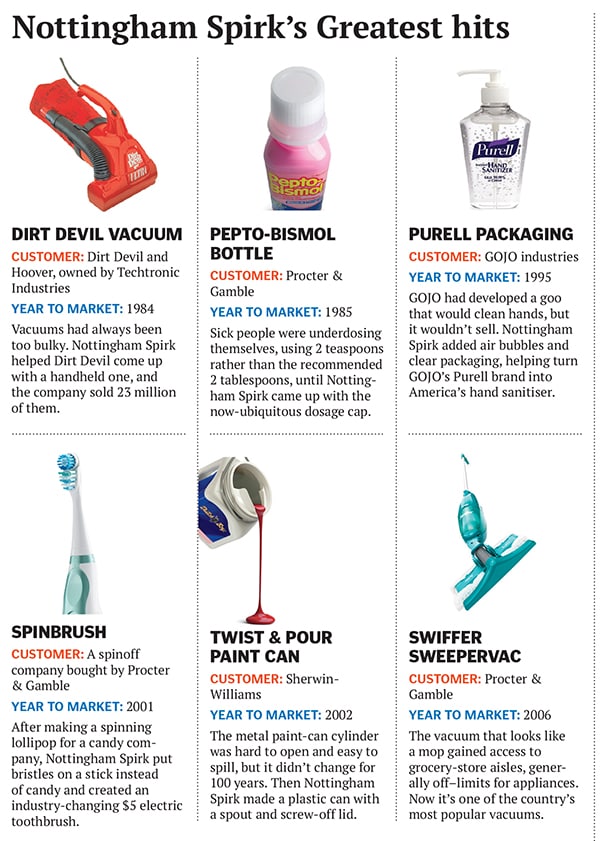

The closest thing in America to Thomas Edison’s New Jersey laboratory is a decommissioned Christian Science church in Cleveland. It’s here that John Nottingham, John Spirk and their team of 70 inventors, tinkerers and support staff have cooked up the Swiffer SweeperVac, Crest Spinbrush, Dirt Devil vacuum and nearly 1,000 other patented products. No, nothing as momentous as the lightbulb or the phonograph, but in their nearly anonymous way—even in Ohio, almost no one has heard of them—Nottingham and Spirk have proven themselves as good at making money as the Wizard of Menlo Park himself.

“We’re probably responsible for more patents than any other company our size,” says Nottingham, 64, who in 1972 set himself up in a garage with a college buddy, John Spirk. The most innovative thing about them: Their model. Rather than invent products and then figure out how to sell them, à la Edison, the Nottingham Spirk Innovation Center invites corporate behemoths—from Procter & Gamble to Mars—to come to it with its product quandaries. Nottingham and Spirk then invent the solutions and give clients a choice of how to pay. They can either fork over cash up front, as much as $120,000 a month, or pay a royalty fee down the road, up to 5 percent of sales. It’s a sliding scale—the more cash at the start, the lower the royalty fee later. “I’ve dealt with a million industrial design firms, lots of agencies, lots of PR firms, and they’re the first ones that really approached us with that model,” says Adam Chafe, who spearheaded Sherwin-Williams’ effort to develop a screw-top paint can. “They had already made money, so they were looking to do bigger things, more revolutionary.” With products like the paint can, the math can get huge: Since 1972, Nottingham Spirk claims, products it developed have generated more than $45 billion in sales.

Nottingham Spirk has proven willing to take equity stakes as well. Its biggest score: Dr John’s, which sold electric toothbrushes for $5 when the going rate was $50. Procter & Gamble bought Dr John’s for $475 million in 2001 (Nottingham and Spirk each got an estimated $40 million on that one). Heady stuff for a guy like Nottingham who, as a college intern, ate lunch by the pond of the General Motors Technical Center, envisioning a corporate life for himself—until one of the company’s top designers disabused him. “He said, ‘John, this is the greatest R&D centre in the world,’” Nottingham recalls. “I’m just drinking it in. I’m just saying, Wow, I’m in heaven, feeding the ducks. Then he dropped a bomb on me. He says, ‘It’s amazing that the most innovative ideas that General Motors has come up with have come from the outside, small companies.’ And I stopped in my tracks, the crumbs going to the ducks stopped in midair. And at that point my life changed. I said if I’m going to be effective, it’s not going to be inside General Motors. It’s going to be outside.” He returned to school for his final year at the Cleveland Institute of Art, where he told his first-year hall mate John Spirk about his new dream—reinventing the world’s largest companies rather than joining one of them. After graduation GM came knocking with a job opening for Nottingham, and Huffy Bicycles had one for Spirk. They rejected the offers and became co-CEOs of their own shop instead.

“There’s a famous Bill Gates quote. They asked him where does he worry about competition from,” says Spirk, 65. “They’re thinking all these high-tech, you know, and he says I worry about two guys in a garage. So what do we do? We graduated school, and two guys moved into a garage.”

Their big break came when they approached Rotodyne, an Ohio manufacturer that mainly made bedpans using a cheap plastic shaping process called rotational moulding. Nottingham and Spirk helped the company use its rotational moulding process to make not only bedpans but also cheap toys for children. The bedpan company shifted its focus and created a new brand: Little Tikes, whose indestructible red-and-yellow cars have become landmarks of toddler culture in America.

Nottingham and Spirk moved out of the garage and took up residence in two facilities, one in an old brownstone where they came up with their ideas and another in a factory where they manufactured them. Eventually they outgrew those facilities, too, and started shopping for a new home. In 2005 they found it: The Christian Science church just down the road from their old art school. Architecturally significant with its rotunda sanctuary and 5,001-piece organ, the building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

But what excited Nottingham and Spirk most was something more practical. The basement Sunday school space could be renovated into a prototyping factory, which would allow them to merge two facilities into one.

The process starts in a research lab in the church’s basement. Designers, engineers and prototype builders crowd into a small room on one side of a two-way mirror and watch through the glass as consumers use products like, say, a bottle of Pepto-Bismol. They take notes, such as how sick people usually take two teaspoons instead of the suggested two tablespoons, underdosing themselves.

The designers then go to work on a solution: For instance, a dosage cup that fits onto the top of the Pepto-Bismol bottle. The product is built in an expansive prototype workshop, complete with industrial-grade saws, paint rooms and 3D printers. Clients walk away with a patent plus a prototype they can send straight to a manufacturer. Sales climbed 30 percent in the year after Pepto-Bismol introduced a cap that measures dosage, and the design is now ubiquitous on medicine bottles.

Nottingham anticipates bigger results (“billion-dollar potential, plus, plus, plus”) from the firm’s latest play: HealthSpot, a kiosk that comes with pullout medical instruments and a high-definition screen that allows for remote, yet face-to-face, medical appointments. It would be the kind of product that Edison would approve of—a game changer for a huge chunk of the world. And it would all emanate from a Cleveland church basement. Says Nottingham: “I see a sea change coming back to the Midwest.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)