Can Craigslist be killed?

Two well-funded startups are battling to build a smartphone-based alternative to Craigslist, the 22-year-old online dinosaur that's been a cash machine for founder and newly minted billionaire Craig Newmark

With an intuitive mobile app, OfferUp CEO Nick Huzar thinks he can win the race to become the new king of classified ads

With an intuitive mobile app, OfferUp CEO Nick Huzar thinks he can win the race to become the new king of classified adsImage: Tim Pannell for Forbes

It’s nearing bedtime for Asher Huzar, but on a Tuesday night at 7.30 he ducks the rules, wriggles out from the dinner table and disappears to the basement for playtime. By the time his father, Nick Huzar, checks in on him, three-year-old Asher has inflated his indoor bounce house, which provides him and his sister, Ava, with 15 minutes of entertainment before they pinball onto the next activity. Raising kids can be taxing, but at least for Huzar and his wife it has been relatively inexpensive. He bought the bounce house secondhand for $100. Huzar then points to Ava’s princess mirror, which he scored for $70. Asher’s Black & Decker toy tool set that supposedly came new from Santa? Just $50.

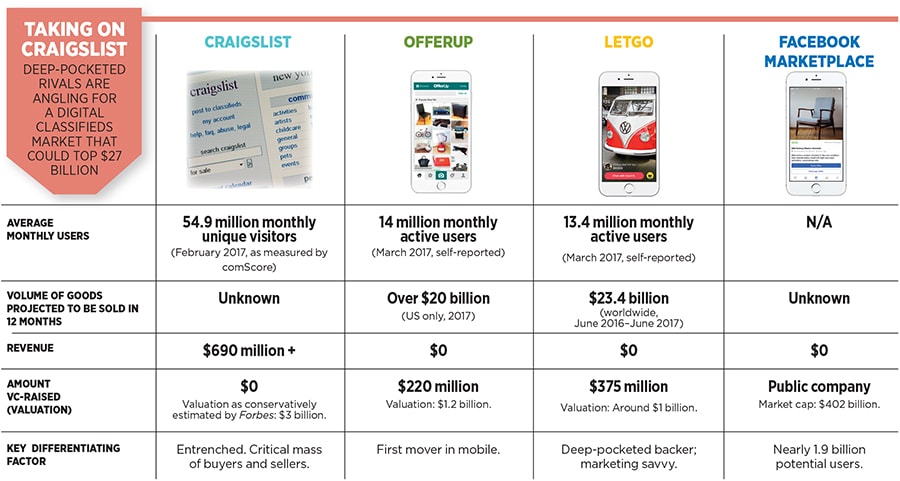

Huzar is the co-founder and CEO of OfferUp, so it’s no surprise he’s raising his children on hand-me-downs bought on the classifieds service he started six years ago. It’s been a dizzying rise for OfferUp, which has outgrown its own playpen days, morphing into a stealth powerhouse that’s on track to facilitate the sale of more than $20 billion worth of goods this year. That’s nearly a quarter of what was sold on eBay in 2016. With a valuation of $1.2 billion, OfferUp has established itself as one of the strongest and most credible challengers ever to Craigslist, that messy website of crowded blue hyperlinks whose iron grip on the online classifieds business represents one of the most unlikely monopolies of the internet era.

In the technology industry, where survival depends on constant innovation, conventional wisdom suggests Craigslist should have vanished long ago. Launched by Craig Newmark in 1995, the website, which has kept roughly the same design through the years and now has some 55 million visitors a month, has not only survived but also thrived. It is the cockroach of the internet age, an ugly but effective ecommerce platform that decimated the newspaper industry by wiping out print classifieds sections and emerged unscathed from technology shifts that crippled mightier contemporaries like Netscape and Yahoo. Craigslist founder Craig Newmark has kept his site virtually unchanged for 22 years

Craigslist founder Craig Newmark has kept his site virtually unchanged for 22 years

Image: Image: Platon/Trunk Archive

Craigslist’s effectiveness cannot be understated. Don’t be fooled by the “.org” in its domain or the accusations leveled at CEO Jim Buckmaster of running the company like a “socialist anarchist”. Craigslist is no nonprofit. In fact it’s a virtual ATM. Last year, it took in upwards of $690 million in revenue, according to an estimate by the AIM Group, a research firm in Altamonte Springs, Florida. With only around 50 employees, some server costs and a few legal bills, Craigslist converts most of those sales into profit. Based on valuations of comparable publicly traded companies, Forbes estimates Craigslist is worth at least $3 billion. That makes Newmark, 64, who owns at least 42 percent of the company, worth $1.3 billion. Neither its CEO nor its founder would speak to Forbes for this story. A company spokesperson said in a statement that “we don’t comment on numbers that are bandied around by media, analysts or others, and never have”.

While Newmark and Buckmaster are getting richer by the day, they are more vulnerable than ever. Despite its success, Craigslist has shunned innovation, refusing to create a mobile app and litigiously pursuing third-party developers that have tried to improve the experience. Huzar argues convincingly that Craigslist’s lock on the secondhand-goods market is coming to an end. When asked how he can be so sure, the 40-year-old Seattleite stops smacking his gum and turns an icy stare to his iPhone. “This device,” he says.

It’s virtually impossible to calculate how many transactions Craigslist facilitates, but a good proxy for the potential of its business (if it were run to maximise profit) is the US newspaper classifieds industry, which reached about $18 billion annually in the late 1990s—or about $27 billion in today’s dollars. That Craigslist pulls in more than $500 million in profit a year without trying illustrates the mouthwatering potential for OfferUp and its competitors.

OfferUp allows users to list almost any item for sale by simply snapping a picture, selecting a price and posting a short description. Buyers can browse local goods in a Pinterest-style photo feed, haggle with a seller through the app and arrange an in-person transaction. “If you look at the amount of stuff sitting there in homes and businesses, in garages and storage units, I think Craigslist is actually small,” Huzar says. “Ninety percent of what we can’t see is just sitting there waiting to be sold.”

The multibillion-dollar question is whether OfferUp can persuade the owners of all that stuff to sell on its platform. Investors such as Andreessen Horowitz and T Rowe Price have plowed $220 million into OfferUp, betting that it is poised to become the Craigslist of the mobile era, despite its negligible revenue so far. But it’s not the only one vying for that lucrative moniker. Other competitors include Letgo, which has raised $375 million, mainly from its majority owner, the South Africa-based internet giant Naspers, and Facebook, which launched its Marketplace service last year. Both are hoping to overtake OfferUp in what many see as a winner-take-all battle. Whichever has the most buyers and sellers, or what economists call “liquidity”, will corner the market, leaving competitors bankrupt. “The classifieds business is about having a natural monopoly,” says Fabrice Grinda, a serial entrepreneur whose startup was acquired by Letgo.

For now, Craigslist remains the rival to beat. Started in 1995 as a mailing list for San Francisco events, the company has flouted just about every maxim taught in business school. By the early aughts, it had assumed the austere layout people are now familiar with: Plain-Jane text links to categories like jobs, personals, for sale and housing. “We have no intent of what people call monetising this,” Newmark, a former code monkey at IBM and Charles Schwab, told the San Francisco Business Times in 2001.

In an era of dial-up internet connections and limited bandwidth, Craigslist’s simplicity quickly attracted users, and it grew as more and more people came online. It was one of the first websites to demonstrate a strong network effect, a phenomenon by which a service gains more value as more people use it. As buyers flocked to Craigslist because it had the most listings, sellers did so in turn because it had the most buyers. Even at wildly successful eBay, some executives eyed this perpetually self-reinforcing economic engine with envy. “There was so much intrinsic momentum from the network,” says Jeff Jordan, a former eBay senior vice president. Now a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, Jordan sees an opportunity: “I think Craigslist has been largely unmanaged for a decade.”

Though the vast majority of Craigslist is used for free, it’s not a socialist endeavour. Early on, to cover costs, the company implemented a $25 charge for posting help-wanted ads in the Bay Area and over the years has instituted fees for select categories, including New York apartments, automobiles offered by dealers and “therapeutics”, a section with offers for massages and other services that law enforcement officials have said are a magnet for illegal prostitution. Those fees were originally implemented to counter spammers, former employees told Forbes, but they quickly turned into an extremely profitable business. Job postings netted some $40,000 a day just from the San Francisco region in the early 2000s, says a former employee.

The times of unfettered profits, however, may be winding down. In recent years, entrepreneurs have found opportunities to build businesses around certain Craigslist categories by providing better features and services. They range from Airbnb for temporary housing, Redfin for real estate services and OkCupid for personals. Collectively, they’re taking their toll. In February, 54.9 million people visited Craigslist, down from 60.9 million for the same month in 2016, according to comScore.

Still, while startups have homed in on sub-categories to compete, none have succeeded yet by going head-to-head with Craigslist’s core “For Sale” section, where users can buy and sell anything. OfferUp is the first to make significant headway. The company says it had 14 million monthly users in March, about a fourth as many as Craigslist. Huzar claims his company is already larger than the incumbent in certain markets. “Yes, a lot of us have bought things on Craigslist, but not a lot of people sell there,” Huzar says. “A lot of people say, ‘I don’t have the time’ or, for women, ‘I don’t trust it—I’m scared.’”

Those hesitations are summed up in the plain principles that guide OfferUp: Simplicity and trust. Posting has to be easy, to lure sellers away from Craigslist, Huzar says, and OfferUp’s four-step process makes it possible to list anything in less than a minute. The marketplace also has to be safe, and with Craigslist’s reputation as a potential place for crime—one blog has counted 110 murders with alleged ties to the site since June 2007—OfferUp has implemented buyer and seller ratings. Users can also choose to “verify” their accounts by using their Facebook profile or a driver’s license.

It’s not perfect. For the uninitiated, the app’s main shopping window can seem like an endless feed of junk ranging from cans of infant formula to counterfeit Ray-Bans. There have been accounts of muggings during OfferUp transactions, and banned items like marijuana are easy to find. Huzar says it’s an “endless pursuit” to eliminate bad actors but one he is forced to endure—a single bad experience can send a user over to Letgo, which offers a similar design and experience.

Alec Oxenford’s Letgo has plowed hundreds of millions of dollars into TV ads to challenge OfferUp

Alec Oxenford’s Letgo has plowed hundreds of millions of dollars into TV ads to challenge OfferUpImage: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

Alec Oxenford, an affable 48-year-old Argentine, who runs Letgo, loves to lob the occasional grenade in his rival’s direction, often repeating that his company launched only in 2015 but is on course to facilitate the sale of more than $23.4 billion worth of goods in between June 2016 and June 2017 in the United States and elsewhere. (Letgo, unlike OfferUp, is active in some overseas markets, including Turkey and Norway.) “We are clearly growing faster than almost anybody in the US,” Oxenford says. “Other players launched six years ago... We believe [our lead] is becoming clearer and clearer, and we are becoming very comfortable.” For its part, OfferUp says it will handily surpass $20 billion in goods sold this year, with about half coming from car sales.

Every few years, someone in Silicon Valley looks at Craigslist and thinks he or she can do better. In the late 1990s, the startled newspaper companies tried collaborating with each other on various projects, and in 2000, Geebo launched as the “safe” Craigslist. In 2004, there was Oodle, a well-financed website that later tried to incorporate Facebook identities. All these efforts basically came to naught. Even mighty eBay has stumbled. It bought a 28.4 percent stake in Craigslist in 2004 and spent years trying to clone it. That led to a seven-year legal battle, which was settled when eBay sold its shares back to Craigslist for an undisclosed amount in 2015. These days, eBay has its own OfferUp clone, though usage peaked at a few million people a month, and the company has been shopping it around for an acquisition, according to one source. (Ebay declined to comment.)

Huzar has distanced himself from the Valley and its past failures, establishing OfferUp in the Seattle suburb of Bellevue. While attending Washington State University, he became obsessed with the computers his Delta Sigma Phi fraternity brothers used to play videogames like Quake and Duke Nukem, so he bought his own with a $2,200 student loan.

Having picked up some coding skills, Huzar landed a job at a frat brother’s startup before bouncing into product management roles at Microsoft and T-Mobile. By 2006, he had become tired of life as a middle manager and started a professional networking website called Konnects. He spent four years constantly raising money to survive, while watching a rising startup called LinkedIn eat his lunch.

By 2010, Huzar threw in the towel, and he and his wife were expecting their first child, Ava. As the couple went into “nesting mode”, Huzar ran into a predicament while clearing out space for his daughter’s nursery: He had plenty of valuable stuff to get rid of, but no time to list them on Craigslist. Instead, he unloaded his stuff at Goodwill, where the parking lot always seemed full. “I asked the people handling the stuff, ‘When do the cars stop?’” Huzar says. “The workers said, ‘They don’t.’”

From that Goodwill parking lot, Huzar wrote the first lines of code for what would become OfferUp. Co-founder Arean van Veelen, a former Konnects employee who no longer works at OfferUp day to day, calls this period their “chicken and egg” phase as they struggled to create a two-sided marketplace with a critical mass of buyers and sellers.

The company greased the wheels by buying products from other users and relisting them on the app. On Huzar’s 36th birthday, he and van Veelen filled a truck with balloons to canvass suburbs, but one of the hired hands was accidentally thrown off the truck. Huzar paid a minor hospital bill and dodged a potential lawsuit that could have ended the company. The efforts started to pay off, gradually, as users outside of their immediate network began listing and buying items. Two and a half years in, on his 15th trip down to the Bay Area in search of funding, Huzar could finally show that his marketplace was on its way to sustainability and secured a $2.8 million investment led by Jackson Square Ventures.

Together, OfferUp and Letgo have now raised nearly $600 million, but there is still a real possibility that Craigslist, which never took VC money, will simply refuse to die. The vast majority of people who visit Craigslist don’t think about online classified ads until it’s time to sell their old bike or tattered couch. But they know it’s there and will likely meet their buying or selling needs—dusty text links and all. Do you need a slick app for something that isn’t part of your daily routine?

OfferUp may be changing habits. In her annual Internet Trends report last June, Mary Meeker, the famous Wall Street analyst turned venture capitalist, said the average OfferUp user spends about 25 minutes a day, usually browsing, on the app, on par with the likes of Snapchat and Instagram. Apparently having a digital swap meet at your fingers can be habit-forming. Last year, when OfferUp’s total volume hit $14 billion after five years, Meeker noted it took eBay three years longer to pass that mark.

Those numbers come with a few caveats, namely that OfferUp, which charges nothing to either buyers or sellers, makes no money. This year the company has begun experimenting with monetisation strategies like in-app payments, ads and promoted posts, but its executives know that meaningful revenue can come only when it cements mindshare. That may be impossible as long as Letgo persists.

OfferUp and Letgo have raised nearly $600 million, but there is a real possibility that Craigslist will refuse to die

While OfferUp employs more than 180 people in an expansive Bellevue office decorated exclusively with items from the service, Oxenford’s app is run by teams split between Barcelona and New York. With a sugar daddy in Naspers, a publicly listed company that last year posted more than $12 billion in revenues, and a television-centric marketing strategy that has worked for Naspers-owned OLX, a sister company whose classifieds sites serve Brazil, India and 43 other countries, Letgo has a plan to flood the American consciousness.In 2016, Letgo spent an estimated $100 million on TV ads in the US—compared with less than $1 million by OfferUp—according to the advertising analytics firm iSpot. This year, as Huzar went on the defensive and bought $5.5 million worth of TV ads in the first quarter, Letgo spent $32 million. “Our competitors by now should probably know that we will do whatever it takes to win,” Oxenford says. “It’s not like we’re operating under disguise. We’re completely visible, and it’s working, no?”

It depends on whom you ask. App Annie says Letgo had 7.3 million monthly active users in February, compared with OfferUp’s 6.3 million. But the stat can be juiced by high download rates affected by ad spending, and both companies report much higher usage. OfferUp says it had 14 million monthly active users on mobile in the US in March; Letgo says it had 13.4 million. The back-and-forth trash talk from the two entrepreneurs suggests the race is close. Huzar dismisses his free-spending competitor as a company that’s “just trying to get us to the table”. Oxenford counters: “Momentum is on our side, and growth is on our side.”

Neither can discount Facebook, which has largely blundered in commerce efforts but needs to engage only a fraction of its 1.86 billion users to make a dent in the market. “Our strength is that we know what people are interested in and we can tailor Marketplace to show your interests,” says Mary Ku, Facebook’s head of commerce products.

While he keeps an eye on Facebook and Letgo, Huzar knows the biggest obstacle on his path to classifieds riches is Craigslist. Can someone finally topple one of the last true mammoths of the dot-com era? His answer is classic entrepreneurial bravado: “I don’t lose much sleep at night over it.” He’s counting on OfferUp being around in a decade, when it’s time to buy Ava her first car.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)