Brian Singerman of Founders Fund: A power player

The VC firm Founders Fund is known for a contrarian approach embodied in its polarising founding partner Peter Thiel. Now Brian Singerman, a games buff from outside the fund's PayPal mafia origins, is taking it to new heights—as long as Thiel's controversial politics does not get in the way

Image: Jamel Toppins for Forbes

Image: Jamel Toppins for Forbes

It was just past midnight after a tense day in late March of 2014, and Brendan Iribe’s emotions were raw as he fired off an email to his closest advisors. Iribe, the 37-year-old co-founder and former CEO of Oculus VR, had just gotten off the phone with Mark Zuckerberg, the 32-year-old co-founder and CEO of Facebook. The two young entrepreneurs were on the verge of sealing a blockbuster deal that would shock the tech industry. The world’s largest social network would buy the world’s hottest virtual reality startup. But with just hours to go, the two couldn’t agree on how the purchase price, based on the value of Facebook’s stock, would be spun. Iribe was adamant that it be called a $2 billion-acquisition, but the math, tied to Facebook’s dipping stock price, didn’t quite add up. The deal was suddenly on life support.

Oculus and its headset, the Rift, were already the toast of the tech world, and Iribe had some of the industry’s biggest names on speed dial. Marc Andreessen was on his board, and Founders Fund, co-founded by Peter Thiel, was an investor. But it wasn’t either one who answered Iribe. It was Thiel’s colleague Brian Singerman, a 40-year-old software geek and one of the newest partners at the firm. By 1 am, with Singerman’s help, Iribe had tweaked the announcement so it would make the Oculus team happy without forcing Facebook to renegotiate terms. Hours later, Facebook announced in a press release that it was buying Oculus for “approximately $2 billion” in cash and stock and $300 million in employee earn-outs. For investors in the two-year-old startup, it was a golden outcome, but Singerman, who had salvaged the deal, was kicking himself. “I was the first investor to commit to them,” he says. “But we could have owned so much more.”

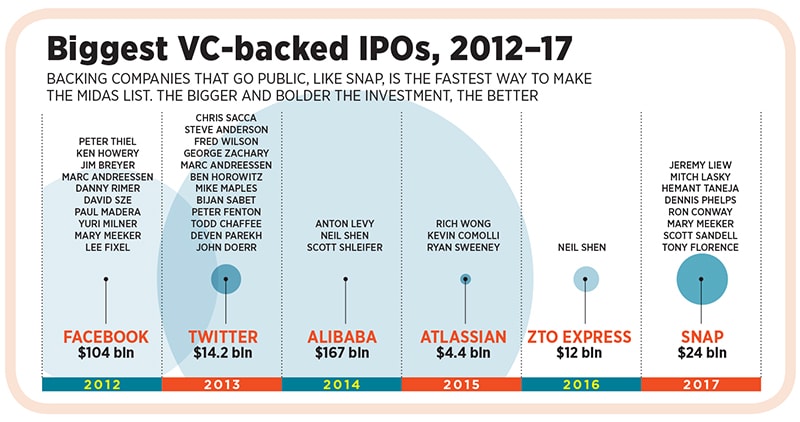

It’s that kind of thinking that has turned Singerman, who is No 5 on this year’s Midas List of America’s top venture capitalists, into the most successful investor at the nerdiest and most contrarian venture firm in the country. Since its founding in 2005, Founders Fund has been known by shorthand as Peter Thiel’s firm. With the election of Donald Trump, Thiel, a vocal supporter and close advisor to the US president, has emerged as the most divisive figure in left-leaning Silicon Valley, equal parts outlier and outcast. He’s been excoriated for “normalising” an administration whose policies many consider anathema to the industry’s interests and values. His presence on the Facebook board has been questioned (though not by Zuckerberg). Some entrepreneurs mutter privately that they won’t take his money, and some VCs vow to keep their distance. Singerman is determined to stay above the fray. “We’re mostly apolitical,” he says about the firm.

Founders Fund is no stranger to controversy. Early on, it declared itself the VC firm for entrepreneurs who didn’t like other VCs. The partners established their lair in the San Francisco Presidio, near the Golden Gate Bridge, 35 miles north of tech investing’s traditional corridor of power on Sand Hill Road in suburban Menlo Park. In 2011, they posted a manifesto that was a love letter to moonshot thinking and a rebuke to their VC peers: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

Often betting on projects their rivals deemed too risky, Founders Fund built a portfolio that’s in another orbit from that of most firms. For every dollar investors put in its first fund, which included Facebook, they took home seven. The second fund may do even better, thanks to bets on successes like Spotify, Palantir and SpaceX. And newer funds have already quadrupled in value, at least on paper, following investments in stars like Airbnb, Lyft and Wish. The firm, which opened with a $50 million fund in 2005, is on track to generate more than $9.5 billion in returns.

One of Founders Fund’s tricks: Back your friends. Along with Reid Hoffman and Elon Musk, Peter Thiel is one of the more famous members of the so-called PayPal mafia, a group of entrepreneurs who worked together at the payments site and got rich when it was sold to eBay in 2002. Thiel invested in PayPal alum David Sacks with Yammer and in Musk’s SpaceX. Palantir, which Thiel helped to start, is in the family, as is Max Levchin’s Affirm. As the clan’s Vito Corleone, Thiel has been the undisputed face of the firm.

Image: Jamel Toppins for Forbes

Singerman’s emergence as a power player changed all that. The firm’s sole non-founding general partner, Singerman has had more exits than any of his colleagues in the past five years, Thiel included. And it’s Singerman who worked hard to nudge his colleagues into biotech in 2012, an industry they knew little about. Not that any of them are complaining. His brazen $300 million bet on Stemcentrx, which makes drugs that attack the stem cells responsible for tumour growth, paid off when it was acquired by the pharma giant AbbVie in April 2016. The investment has single-handedly delivered a profit of $1.4 billion.

On the top floor of a large anonymous office building near the entrance to the Presidio, three of Founders Fund’s partners are conducting a postmortem on a startup pitch from early March. With Singerman presiding from behind a standing desk, Scott Nolan and Cyan Banister say the startup’s founding team is strong and experienced and onto a smart strategy for using technology in agriculture. But Banister says she’s met with a handful of similar companies. After 15 minutes, the trio decides to wait until a clear winner emerges, so the firm can pounce with a larger cheque.

Founders Fund reached the top echelon of venture capital through highly concentrated bets on just a handful of companies, spotting a market leader first and then continuing to press on the scale with its subsequent funding rounds. It’s a calculated approach that’s also risky. And yet Founders Fund has never written off more than $10 million on a bad deal. “That’s what you sign up for,” says Dan Feder, a Founders Fund investor who oversees portions of Washington University’s endowment. “There are very few VCs out there with that ability to identify and go large in what will be great companies.”

Rewriting the VC playbook has been Founders Fund’s approach since it began. Thiel and co-founders Ken Howery and Luke Nosek had met with dozens of venture investors while building PayPal, and they were not impressed. One helped to start a competitor. Another tried to replace the founders with an older management team. Flush with cash from the 2002 PayPal acquisition by eBay, the trio was already investing in friends’ startups, helping Thiel run a small personal fund. “We spent a whole year asking, ‘How do we make a venture capital firm that we actually like?’” Nosek says.

Their version of VC, characterised by the name Nosek came up with, would live and die by a startup’s founders. The firm wouldn’t veto a financing round, push a company to sell or even demand a board seat. And when a startup faltered, Founders Fund wouldn’t force out its founders.

Founders Fund made a splash early on thanks to its ties to Facebook. Thiel, dipping into the firm’s initial $50 million fund, became the first investor in Zuckerberg’s social network, eventually turning $8 million into $376 million. Shortly after, Facebook President Sean Parker joined as a general partner. Following a string of successful bets, Founders Fund raised eyebrows across the Bay Area in 2008 when it put $20 million into SpaceX, the rocket startup founded by Musk. “It wasn’t clear to anyone that this was going to work,” Howery says. “Every rocket had blown up.” One potential investor walked away. Another accidentally copied the partners on an email that said they’d lost their minds. While SpaceX’s future remains uncertain, it is currently valued at $12 billion, 8 percent of which belongs to Founders Fund.

As its funds grew—to $225 million, $250 million and $625 million—the firm remained, in the words of Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup, the “Peter and Sean show”. That began to change when Singerman, who had been hired as a senior associate in 2008, was promoted to partner in 2011, effectively replacing Parker, who had stepped back to pursue other ideas. In those years, Founders Fund struck gold again with the AI startup DeepMind, acquired by Google for more than $500 million in 2014, and The Climate Corporation, which uses sensors to monitor weather, soil and field conditions to improve crop yields and was acquired by Monsanto for $1 billion in 2013. The firm’s $150 million investment in Airbnb is now worth about $1.4 billion, and the $100 million it put into Stripe has roughly quadrupled in value. Its largest investment by far, however, would come in stages between 2012 and 2015. It was Singerman’s increasingly bold bet, adding up to $300 million, on Stemcentrx. In April, AbbVie acquired Stemcentrx for up to $10.2 billion. Founders Fund owned about 16 percent.

Singerman might have become a professional gamer, not a VC, had that industry matured a few years earlier. He grew up in Los Angeles, the son of a doctor and a teacher. Early on, he developed an affinity for computer programming and something of an obsession with games. In the 1990s, he won national tournaments for Settlers of Catan, a popular strategy board game. While at Stanford, he spent a summer abroad in Europe, in part to kick an addiction to the online role-playing game EverQuest, on which he spent more time than his computer science classes.

After a gig at a failed startup, Singerman headed to Google in 2004, where he helped launch a personalised home page called iGoogle. Word quickly spread that he was a champion player of a 2002 fighting videogame, SoulCalibur II. When colleagues challenged him to a game, Singerman agreed to play as long as there was money on the line. At pre-IPO Google, some of his colleagues were short on cash. “What they did have was a lot of equity,” he says. His winnings came in the forms of IOUs, which rivals made good on following the Google IPO, when they were able to sell some of their shares.

Singerman went on to invest in startups and launched a $1 million fund called XGYC (short for “ex-Google, Y Combinator”, after the accelerator where he found most of his deals). He sought out mentorship from two pre-eminent investors in seed-stage deals: Ron Conway (ranked No 43 on this year’s Midas List) and Steve Anderson (No 4), who helped Singerman find his first major win in Heroku, which Salesforce acquired for $212 million in 2010.

Singerman also drew the attention of Parker, who saw him as a way to add a network of Googlers to Founders Fund’s heavily PayPal- and Facebook-influenced deal flow. In 2008, Parker persuaded him to join the firm on a short-term trial. As one of just two junior investors there, Singerman met with more than 1,000 companies in his first year.

On a recent Thursday night, Singerman’s gaming chops are on display as he smokes a group of friends at a board game called Scythe. It’s the first time any of them has played. He’s not above staying up the night before, cramming YouTube tutorials on a game’s strategic intricacies.

Being a methodical researcher has also helped Singerman’s investing. He jumped into Oculus ahead of others when he realised its VR headset could someday be more than just a gaming rig. He saw massive upside in Airbnb’s potential to expand into services that supplement rentals. And he’s applied his skills to areas as diverse as wearables (Misfit) and classroom tech (AltSchool). Singerman had been devouring research on health care ahead of his meeting with Mario Schlosser, the CEO of Oscar Health, which focuses on low-cost health insurance. “In half-an-hour, he called up his partner Ken to say he had to look right away,” Schlosser says. Schlosser and co-founder Josh Kushner, who are based in New York, decided to stay in San Francisco for an extra day, staying up most of the night discussing Oscar over beers with Singerman and crew. Founders Fund later became the biggest outside investor in Oscar.

Despite the healthy returns from Oculus, Singerman’s personal disappointment in not securing a larger stake cemented a change in his investment approach. At AltSchool, he co-led multiple rounds. At Climate Corporation, he wormed his way into the Series C after failing to get into the earlier rounds and ended up buying more shares from company insiders to maximise his position.

No deal would embody his doubling-down approach better than that involving Stemcentrx. Singerman had been studying biotech efforts to stop various forms of cancer when he met co-founder and CEO Brian Slingerland at a coffee shop near his house late in 2011. After a brief chat, he urged Slingerland to come to Thiel’s house that night for his holiday party. Slingerland hesitated because it was his first wedding anniversary but decided he couldn’t pass up the opportunity. Rather than take his wife out for a romantic dinner, he spent the evening huddled with Singerman, Thiel and other partners, talking cancer stem cells.

If Singerman had any doubts about Stemcentrx, they were dispelled when the experts he sent to evaluate the company asked to invest themselves. When he told friends he was ploughing large sums into the biotech, they wrote it off as typical Founders Fund zaniness. “I said, ‘You are smoking crack’,” says former Hollywood agent Michael Ovitz, who had grown close to Valley VCs like Andreessen and Thiel and ended up investing in Stemcentrx alongside the firm.

Eager to increase his position, Singerman manoeuvred to lead Stemcentrx’s next round, in 2014, after one of the company’s drugs began to show promise. Through company insiders he bought up additional shares—whatever he could find. By the time of the negotiations with AbbVie, Singerman was all in. He clocked nights and weekends at the biotech’s headquarters in South San Francisco. When the founders debated whether to sell the company, Singerman characteristically didn’t push either way. “He helped us think through all the different options, then he said, ‘You are the founders’,” Slingerland says. Singerman retorts: “What was I going to say? ‘Cure cancer faster?’”

On election night, at the house of Dustin Moskovitz, the Facebook billionaire co-founder who had donated $35 million to support Hillary Clinton, Singerman watched Donald Trump win the presidency. Nobody there had voted for Trump. Singerman’s partner Thiel made plans to head to New York to become a key power broker in Trump’s transition team. When the leaders of the tech world, such as the CEOs of Alphabet, Amazon and Apple, appeared at Trump’s headquarters in December, Thiel sat directly to the left of the president-elect.

To colleagues, Thiel’s foray into politics is just classic Thiel—a new project to go alongside the hedge fund, family office, non-profit foundation and book tour. “He’s always had a thousand things going on,” Howery says. But to many in a rapidly politicising Silicon Valley, this felt different. At a conference in June, Ryan Petersen, the CEO of one of Founders Fund’s most promising startups, Flexport, played to the crowd by declaring, self-servingly, that he’d “probably not” take Thiel’s money again because of his politics. On election night, David Heinemeier Hansson, the Danish creator of popular web app framework Ruby on Rails and bestselling author, tweeted to his more than 200,000 followers that Y Combinator (where Thiel is an advisor) could have its next batch of companies work on a deportation app—pointedly adding the #foundersfund hashtag.

Then came the calls for Facebook and Y Combinator to cut ties with Thiel. Both Zuckerberg and Y Combinator President Sam Altman refused. Privately, several investors told Forbes that startup founders they knew had turned down meetings with the firm because of Thiel. Mark Suster of Upfront Ventures says he’s troubled by Trump’s views on issues like race, LGBTQ rights and health care. “I’d love to know [Thiel’s] views on those topics before co-investing with him,” Suster says. A handful of other VCs echo those feelings privately. The implication: Thiel’s association with Trump won’t help, but Founders Fund won’t miss the small deals it never sees.

The clash over Trump also caused some ripples internally. One partner, Trae Stephens, joined Thiel on the transition team. Another, Geoff Lewis, posted a blistering internet missive declaring, “A world in which president Trump makes any sense at all is not the world I want my grandchildren to inherit.” Lewis also tweeted of those joining the transition: “How quickly principles trade for but a roll of the dice at the roulette wheel of a baking kleptocratic pie.” (He later deleted his entire Twitter history.)

In the office in February, Nolan, Stephens and Singerman look shocked when a visiting founder asks them whether politics, specifically Trump’s immigration policies, impact their investments. “No one’s asked us that before,” Nolan says. Later, Singerman is still simmering about the notion that the firm needs to take public positions on what he sees as private political views.

Thiel has been circumspect in recent months. During February and March, he joined the other partners on occasion, typically by phone or videoconference, to discuss several large (and still secret) deals. When Forbes finally tracks him down, albeit remotely, in Europe, Thiel says that because the firm makes only a “few key investments” each year, his varied interests help him to “think better about the big picture”. And he insists his politics has no bearing on the firm. “My role at Founders Fund is as an investor, period,” he says.

In the end, odds are that the rumblings over Thiel’s love affair with Trump will be little more than noise, as money and greed win out over politics and principle. So far, the only person to publicly return Thiel’s money wasn’t the CEO of one of his portfolio companies but a 21-year-old Thiel Fellow. Meanwhile, Petersen, the Flexport CEO who said that in a do-over he wouldn’t take Thiel’s money, says he’s had a constructive conversation with the partners, including Thiel, about politics. The upshot? “I regret what I said and will gladly take additional investment from Founders Fund if the opportunity arises,” Petersen now says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)