Bank of America's CEO has no great plans. And that's good

Other than cutting costs and strengthening capital, Brian Moynihan has no grand plans for Bank of America. Amen to that

Brian Moynihan sits at a large polished wood table in a windowless conference room clad in his bankerblue pinstriped suit and standard red tie. This isn’t Bank of America’s headquarters, but it may just as well be Moynihan’s home away from home. He is on the 10th floor of BofA’s Washington, DC office tower, which, by no coincidence at all, is directly across Pennsylvania Avenue from the United States Department of the Treasury.

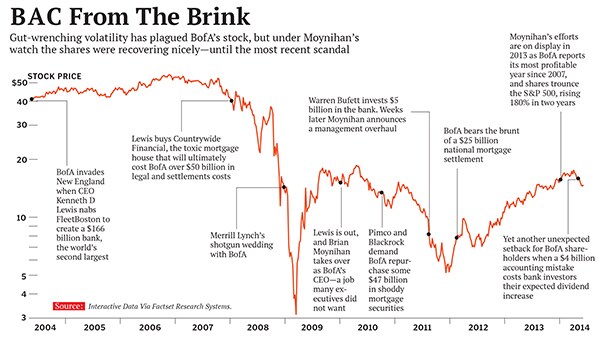

Just three days prior Moynihan sheepishly revealed to federal regulators that there was an accounting error on his bank’s balance sheet that would result in a $4 billion hit to its regulatory capital. The bank was forced to suspend its plan for a dividend increase and a $4 billion share repurchase. After making an impressive comeback over the last two years, its stock fell precipitously and now sits about 20 percent lower than its recent high of $18. Though less troubling than JPMorgan Chase’s London Whale fiasco, it is yet another setback in Bank of America’s rehabilitation and redemption among stockholders.

Their concern, of course, is that Bank of America has merely gone from “too big to fail” to “too big to manage”.

“We were right on the edge of starting the next step in healing, which is to return common equity dividends,” says Moynihan. “Now [investors are] saying, ‘How could you have gotten so close and have it stopped?’ We’re just disappointed.”

For Moynihan, 54, the last four-and-a-half years as the bank’s chief executive have been exhausting. Damage control, cost-cutting and extinguishing legal fires have consumed his tenure. He is tasked with running one of the world’s largest financial institutions, yet at the same time he must wear a government-imposed straitjacket that in many ways turns the role of megabank chief executive into little more than a conservatorship.

It’s not without good reason. Like other giant financial firms, Bank of America went from being awash in profits in the early 2000s to being the recipient of two federal bailouts that totaled $45 billion during the crisis. The hangover from the mortgage-fueled party is still being felt. Through March 2014 Moynihan has settled and reserved $55 billion related mostly to troubled mortgages, including some $23 billion for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and $2.4 billion for bond insurer MBIA. Much of BofA’s stock market value has evaporated. Precrisis, shareholders enjoyed a stock price of $54 and a $245 billion market capitalisation. BofA shares sank to as low as $3 in early 2009, and today, after massive equity dilution, they trade at $14.71.

For Moynihan, who took over in January 2010, the low point may have been August 2011, when he faced an inquisition of questions from 6,000 investors on a conference call orchestrated by Bruce Berkowitz, the activist value investor of $8.5 billion mutual fund Fairholme Fund.

At the time, the bank’s share price had fallen more than 30 percent in a little more than a week and was hovering around $7.50. Countrywide, its toxic mortgage-flogger subsidiary famous for liar loans, no-doc mortgages and a chief executive who epitomised the ugliness of corporate greed, was imploding and making headlines daily. Normally passive institutional investors like Pimco and Blackrock were pounding on Bank of America’s door, demanding it buy back billions of dollars’ worth of faulty mortgage-backed securities.

The Federal Reserve had flat out denied the bank’s request for a dividend increase, and shareholders were suing over its arranged marriage to Merrill Lynch, claiming that Bank of America was agreeing to billions in obscene bonuses for executives and other employees while it was hiding crucial information about the troubled investment bank’s health prior to the deal. Likewise inside the company, Merrill Lynch brokers and bankers harboured deep resentment for their new, seemingly rudderless bank parent.

At one point in 2011 Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois took to the Senate floor with a Bank of America debit card in his hand and urged the public to “get the heck out of that bank”. Bank of America’s shares fell below $5 later that year, down 58 percent in 2011 compared to a flat S&P 500.

In the midst of the storm, Moynihan and chief financial officer Bruce Thompson manned up to the Berkowitz conference call, facing an angry mob of institutional and retail investors. But what Moynihan had to offer during the 90-minute phone call was no magic bullet. What lay ahead for the $2 trillion bank was a straightforward, even boring strategy of cutting costs, selling off noncore assets, building capital and serving its existing customers better. It was the banking equivalent of a Keep-It-Simple-Stupid strategy.

That was just fine by Berkowitz, who already owned some 100 million Bank of America shares, which represented 6 percent of Fairholme’s portfolio. Accustomed to playing turnarounds, he was clearly betting that the giant institution’s stock had nowhere to go but up.

Berkowitz would find himself in good company. Two weeks after the conference call Warren Buffett telephoned Moynihan’s New York City office. The two had never met, but Buffett had done his research and was about to make a $5 billion investment in Bank of America. Moynihan, still insisting the bank didn’t have a severe capital problem, told him the bank didn’t need Berkshire’s money.

Moynihan recalls Buffett’s response: “He said, ‘I know. I wouldn’t be calling you if you did.’” What Moynihan did need was the surge of confidence that comes with any War- ren Buffett investment. “We did the deal over the next 24 hours,” he says.

For Buffett the Bank of America deal had little downside risk. He was buying preferred shares in what was essentially a government-backed entity that, unlike Treasury bonds, would pay a 6 percent annual dividend. He also would get an equity kicker in the form of warrants for 700 million shares. (Bank of America shares are up a whopping 110 percent since Buffett’s investment.)

Of course, shrewd and cautious Buffett (his first rule of investing: Don’t lose money) may not have been counting on any miraculous turnaround at Bank of America but rather was buying a cheap long-term call option on the future of banking. Like other too-big-to-fail banks, Bank of America is transforming itself into a somewhat boring utility, not unlike AT&T of old.

Indeed, deleveraging, or shedding assets, has become a global obsession in the industry. Proprietary trading is gone, investment banking departments have shrunk, mortgage servicing is not worth the capital and far-flung operations are being sold off. In short, the fun has been taken out of commercial banking. The best strategic move a big bank can make these days is to hike its dividend or announce a share buyback.

Brian Moynihan inherited Bank of America from generations of empire builders. In the 1980s and 1990s Hugh McColl turned Charlotte’s North Carolina National Bank into NationsBank by consolidating superregionals in the Southeast and then capping off his career by merging with West Coast giant BankAmerica in 1998. Then his understudy, chief executive Ken Lewis, upped the game by buying FleetBoston Financial, Chicago’s LaSalle Bank, Countrywide Financial and finally Merrill Lynch, in an acquisition that would contribute to his downfall but ultimately give BofA 302,000 global employees and hundreds of offices.

But Moynihan arrived at the top after banking’s 2008 ‘Come to Jesus’ moment. The new banker is a throwback to a bygone era when banking was a profession for principled and well-born Ivy Leaguers, and for hardworking accountants and lawyers. Moynihan, who fits the bill in many ways, needs to be the antithesis of an empire builder.

Born and raised in Marietta, Ohio, a small town in the southeast corner of the state near West Virginia, Moynihan is the sixth son of eight children in an Irish Catholic family. His father was a research chemist at DuPont and his mother a homemaker. He went to public schools and was an honour student who played football and ran track. At Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, Moynihan studied history and was co-captain of the rugby club. From there he went to Notre Dame Law School and then worked on bank mergers for the Providence office of law firm Edwards & Angell. At age 34 he pivoted from law to banking when he was hired by FleetBoston CEO Terrence Murray in 1993. Colleagues describe Moynihan as a hard worker who is smart but unassuming and has a tendency to speak too fast. (Says Moynihan, “People ask, ‘Why do you eat quickly and speak quickly?’ and I say, ‘If you have 10 people at the table every night, you start to learn if you don’t do those two things, then you starve and you’ll never get a word in.’”)

Says Anne Finucane, global strategy and marketing officer for Bank of America, “I think Brian is a different kind of chief executive. His sport is rugby. Have you ever seen rugby? You can’t tell one player from another, and they’re in a scrum, but somebody is running the show. That’s kind of Brian. He doesn’t need to be in the spotlight.”

But inside Bank of America’s scrum, which at times has been brutal if not bloody, Moynihan is slowly getting things done, selling assets, settling lawsuits and attempting to rewire the place so that it is less focussed on product and footprint growth and more focussed on servicing existing customers.

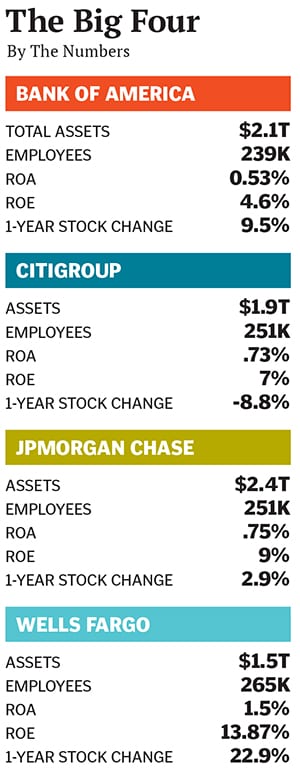

After three years of consecutive declines, revenue finally increased in 2013 to $90 billion, up 7 percent from the prior year. Profits nearly tripled in 2013 to $11 billion from $4 billion. And despite its recent embarrassing accounting error the bank’s revised Basel III Tier 1 common ratio still looks healthy at 9 percent, exceeding the proposed minimum of 8.5 percent required of the bank by 2019. Since 2012 BofA stock is up 164 percent while JPMorgan is up 64 percent, Citi 79 percent and Wells Fargo 72 percent.

“Moynihan has surprised a lot of people by hanging in there and slugging it out,” says independent bank analyst Nancy Bush. “He was dealt a bad hand of cards right up front.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge of Moynihan’s career has been cleaning up Countrywide. To fix it, or at least stanch the bleeding, Moynihan brought in Terry Laughlin, a trusted colleague from his days at FleetBoston Financial.

Laughlin was just off a stint working for hedge fund billionaires like John Paulson and George Soros, who had bought IndyMac, another troubled subprime-mortgage company. Laughlin waded through the mess and created from it a healthy community bank in southern California. Moynihan needed Laughlin to repeat his performance at Countrywide, so Laughlin set up a bad bank known as Legacy Assets & Servicing. Laughlin also built a new mortgage-servicing platform, because the existing one wasn’t able to handle the large volume of loan modifications, short sales and foreclosures. LAS has worked through 3 million delinquent loans it has faced, and it has 275,000 more to go.

With Laughlin ‘handling’ Countrywide, Moynihan focussed on another core competency of postcrisis banking—downsizing. At the end of 2011 he unveiled Project New BAC, a programme designed to save an estimated $8 billion annually by mid-2015. Much of the savings will come from firings and eliminating things like unnecessary data centres and other noncore assets.

Today Bank of America employs 239,000 people, down from 284,000 in 2010, giving it a smaller head count than JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Wells Fargo.

Of course, in order to reduce payroll, Moynihan has been selling off assets: Its Canadian credit card, its Spain card and its Virgin Money Partnership, as well as LaSalle Global Trust, Columbia Management and Merrill’s overseas wealth management business. In total, the bank has shrunk its legal entities from over 2,000 to 1,300 and has sold more than $70 billion in noncore assets. Its risky proprietary trading operation, now prohibited by the Volcker Rule, was among the first to go. As a result its capital markets balance sheet is down to about $600 billion from $1 trillion in 2009.

A smaller and in some ways simpler Bank of America will give Moynihan more time to focus on what could be his most important legacy: Changing the bank’s culture.

“We’ve fine-tuned the business around basic principles: Who are our customers? What do they need from us? And what can we be good at?,” Moynihan explains. “Changing the mind-set requires getting people to stop thinking about the market share, and start thinking more about the value of a product for the customer.”

Putting consumers’ needs first instead of pushing products may sound like an obvious thing to do, but those who have worked under previous Bank of America CEOs say this has never been a top priority.

Even former chief executive Hugh McColl admits that his get-big-or-go-home approach created problems for Bank of America. “One of the problems I had running the bank was marketing would come up with some idea to sell a product, but we’d never sell enough of it. The problem would be we’d have to keep the damn product and support it even though it didn’t make any money,” McColl says. “What Brian has done is get rid of a lot of that.”

Under Lewis, who succeeded McColl and left the bank at the end of 2009, Bank of America became even more product-driven, including the goal of having as many credit card and checking accounts opened as possible.

Today, the bank isn’t focussed on new customers. It’s all about getting to know existing ones better and wringing more profits out of the relationship. In other words, providing a jumbo mortgage to a Merrill Lynch client, opening a Merrill Edge investment account for a retail banking customer or transferring a middle-market company’s retirement plan to Merrill Lynch. It’s a return of the old synergy strategy combined with a heavy dose of cross-selling.

“Brian has really broken a lot of traditionally held beliefs and, quite frankly, sacrificed some earnings to do the right thing for the customer,” says Laughlin.

For example, Moynihan had the bank change an over-draft policy that allowed customers to swipe their debit cards and buy items despite insufficient funds. This earned BofA lucrative fees amounting to an estimated $2 billion per year, but pissed off customers, who were being charged what amounted to usurious interest rates. Moynihan also assigned Laughlin, now president of strategic initiatives, the task of simplifying bank processes. Example: Reduce BofA’s checking account options from 70 to three. Says Laughlin, “It’s not about stretching for every last dollar from a client. That’s a big change.”

To be sure, Moynihan’s back-to-basics approach is not without potential. The bank currently has 50 million customers, but its share of their wallets is only 20 percent. The story is similar in its credit card business, where Bank of America has $95 billion in balances but says its customers have another $90 billion with competitors.

On Merrill Edge, the largely digital brokerage service for customers who have between $50,000 and $250,000, assets stand at $100 billion, up from $40 billion two years ago. But the opportunity is in the trillions, BofA executives say. In all, the bank estimates it has the potential to win more than $8 trillion from its existing customer base.

The changes Moynihan is trying to make will not be easy. It’s one thing to dole out $200 bonuses to bank tellers who open checking accounts tied to active direct deposits; it’s another thing to keep the bankers and bro- kers of Merrill Lynch happy in the new era of low-cost, low-risk banking.

Perhaps to prove a point to employees and to investors, Moynihan is among the lowest paid of all bank chief executives. Last year he made $14 million, compared with $20 million for JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon and $23 million for Goldman Sachs’ Lloyd Blankfein. Even Bank of America’s CEO, former Goldman banker Thomas Montag, who runs Merrill Lynch, earned more than Moynihan in 2013, with $15.5 million. Says Moynihan, “This is not about me. I have this job for a short time. What we have to do is build a lasting capability. The other thing is that you always have to have a healthy fear of what could happen if you don’t get this right.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)