Rapid testing: Race against time

After a slow start, will India's efforts to ramp up testing for Sars Cov2 or the coronavirus be quick enough?

In India, phone booth or kiosk testing is being actively explored to contain the spread of cornavirus. Kiosks were installed at Ernakulam Medical College in Kerala on April 6

In India, phone booth or kiosk testing is being actively explored to contain the spread of cornavirus. Kiosks were installed at Ernakulam Medical College in Kerala on April 6Arun Chandrabose / AFP via Getty Image

Until March 20, the only way to get tested for Sars Cov2 in India was if you’d travelled abroad or come in contact with someone who had and reported a fever, cough or difficulty in breathing. And even then it was incredibly hard to get tested.

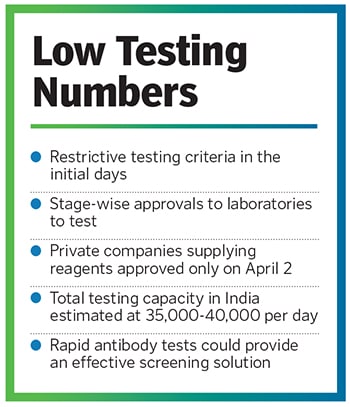

The strict testing definition for a virus that had been declared a pandemic masked the crucial lack of testing capacity. In order to get tested, one had to report to a government facility and have nasal or throat swabs taken. They were sent to the National Institute of Virology in Pune and results were made available two days later. With a testing criteria narrowly restricted to foreign travel, it’s hardly surprising that India had conducted only 13,316 tests by March 20 with 236 testing positive. During March, which would later turn out to be a crucial month, scores of travellers with flu-like symptoms slipped through.

By then the speed of the virus’ spread had taken the world by surprise. Just like in India, the initial low infection rates in Italy, Spain, the UK and US had lulled governments into a false sense of calm. “It was the virulent nature coupled with the long incubation period that allowed the virus to spread unhindered,” says Dr Harish Mahajan, chairman, Center for Advanced Research in Imaging, Neuroscience and Genomics. This was unlike Sars, which took three days to incubate, making it was easier to isolate infected people.

While the government has steadfastly maintained that the lack of testing capacity is not to blame for its decision to restrict the initial rounds of testing, interviews with people who run laboratories and make testing kits suggest that crucial time was lost in February and early March. Had larger numbers been tested (along with stricter quarantines for international travellers), isolation decisions could have been taken earlier. “Our (and the world’s) biggest problem was that we didn’t have a model to follow and so we had to make things up as we went along,” says the founder of a company that has recently received approval for testing kits.

In a situation where every day makes a difference in the infection curve, the steps taken by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) were incremental. As a result, laboratories are still struggling to get testing kits and deploy them and, while rapid antibody tests have been approved, the earliest deployment is at least a fortnight to a month away. “Our aim is to first stop transmission and flatten the curve,” says Dr Rajni Kant, director, planning and coordination, ICMR, pointing to the fact that its containment strategy hasn’t worked.

Testing Infrastructure

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

R Kailashnath, Managing Director, CPC Diagnostics

R Kailashnath, Managing Director, CPC Diagnostics Chandra Sekhar Nair, Chief Technical Officer, Molbio

Chandra Sekhar Nair, Chief Technical Officer, Molbio