India's PPE crisis puts workers in the line of fire

With a broken supply chain and inadequate stocks, health care workers face an acute shortage of protective gear and the risk of contracting coronavirus

The shortage of PPE for health care workers is a global issue. In India, they have had to use raincoats and scarves in the absence of masks

The shortage of PPE for health care workers is a global issue. In India, they have had to use raincoats and scarves in the absence of masks Image: Yogendra Kumar / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

These are unprecedented times for those at the forefront of the battle against the coronavirus. A doctor at a government hospital in Kolkata laments the conditions in which health care personnel have to work during the pandemic. From using raincoats as personnel protective equipment (PPE) to being told to buy masks themselves at exorbitant rates, and from dealing with the fear of contracting the virus as they treat patients to facing social ostracisation, it has been an uphill task in these stressful times (See box: 'A Dispatch From A Hospital').

The acute shortage of PPE for health care workers is a global issue. Reports have emerged of extreme cases in India where nurses and health care workers were forced to use motorcycle helmets as protective clothing, while others are compelled to use scarves to cover their faces in the absence of masks. Doctors and health care workers in countries such as the US, Italy and Spain—some of the hardest hit by the pandemic—have protested against the lack of PPEs, taking to the streets and to social media.

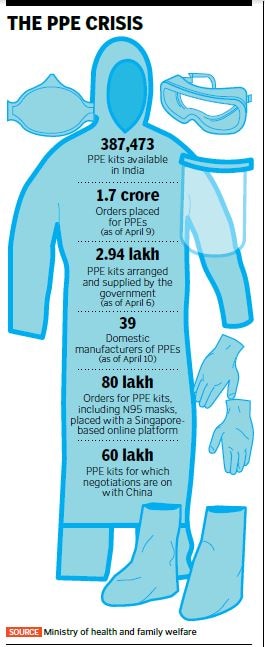

With at least three health care workers succumbing to Covid-19 in India, and at least 80 more testing positive as of April 12, the question remains as to whether they are being provided with adequate PPEs. Normally, PPEs are used in hospitals for surgeries and for treating infectious diseases. But now they are a necessity for all heath care workers, including those who are conducting door-to-door checks for people with symptoms of Covid-19 infection.

Utkarsh Sinha, managing director at Bexley Advisors, a boutique investment bank, says, “It is easy to have the benefit of a 20:20 hindsight, but the sad truth is that our health care infrastructure is stressed, and has been for a while. We simply lack the capacity for providing adequate care at scale. That said, there is little more the establishment could have done to ensure equitable access in this situation.”

According to media reports, by June, India will need 27 million N95 masks and 15 million PPEs, which include face shields and goggles (which are reusable), triple layered medical masks and N95 respirator masks (both reusable until soiled), gloves, coveralls and gowns, shoe covers and head covers (all non-reusable). The demand far exceeds supply, which has been hit by the lockdown that has been imposed in several countries around the world, especially those, such as South Korea, Singapore and China, from where India imports PPEs. Procurement of raw material has become difficult, as has the movement of goods from one country to another, and even within the same country.

On March 23, the ministry of textiles said in a statement, “Such materials [that fulfil the technical and standard requirements for coveralls] are manufactured by a few international companies, who expressed their inability to supply on account of a complete glut in stocks and ban of exports by the source countries. Only a limited quantity was offered and procured by the procurement organisation of the ministry of health and family welfare (MoHFW).”

On January 31, India banned export of all PPEs to ensure enough stocks for use within the country, but on February 8 the ban was revoked on everything except coveralls and N95 masks. Rajat Garg, co-founder of myUpchar, a Delhi-based online health service platform, says between February 8 and March 19, however, when the ban was reimposed, Indian manufacturers exported a large amount of PPEs, since at that time the number of infections in India was low and Indian manufacturers wanted to earn high profits. This led to the existing stock of PPEs in the country being greatly reduced.

“A lot of large hospitals have bought PPE kits for doctors, but not for the technical staff and nurses. These hospitals are asking staff members to buy PPEs themselves. In smaller hospitals, even doctors are being asked to buy them themselves,” says Garg. The government has also rationed the distribution of PPEs among health care workers, depending on whether they fall in the categories of high risk, moderate risk and low risk.

Hospitals have seen a fall in revenue as the volume of surgeries, pathological tests and sale of medicines have fallen. Hence, they are not keen on spending additional money on PPEs. In some cases, NGOs are supporting hospitals by providing them with PPE kits, as and when required.

Garg adds that most vendors who provide PPE kits in India take minimum orders of 500 to 1,000 kits. While this is not a problem for large hospitals, smaller hospitals and those in Tier II and III cities don’t need so many PPE kits. However, they can’t place orders of smaller size. myUpchar is working with vendors to ensure supply of orders of five to 10 PPE kits, although the cost for smaller orders is higher than for bulk orders.

With a broken supply chain, “there is a lot of unpredictability where input costs are concerned”, says Sinha, thus pushing up retail prices. Garg says the retail price of a PPE kit is usually ₹400 to ₹500, but now manufacturers are selling them for between ₹1,100 and ₹1,200, while retail prices are between ₹1,500 and ₹2,000. “With low volume, suppliers are not ready to give you big profit margins,” he adds.

Sinha of Bexley Advisors says, “It is in the larger interest of the community that there is centralised coordination on the procurement and adequate distribution of PPEs.”

To make up for the shortfall in supply, PPE manufacturers in India have increased their production capacities. For instance, 3M, one of the leading manufacturers of respirators, masks and PPE kits in India, is producing about 40 percent more than its normal capacity; its output of alcohol-based santiser has also increased by 50 percent. “When the lockdown was announced, we had material stranded in various parts of the country; there were challenges in accessing raw materials from suppliers who were unable to work; clearances of imports were delayed. It was also difficult to arrange for transportation for our plant employees,” says Ramesh Ramadurai, managing director, 3M India, which has plants in Pune, Bengaluru and Ahmedabad, and imports materials from global subsidiaries.

“The major challenge we continue to face is the lack of international flights and freighters to move materials, but by and large we have not had too many problems with the import of materials that support manufacture of masks and sanitisers,” he adds.

Also, players in related industries and technologies are adapting existing infrastructure for the purpose of making PPEs. For instance, while coveralls are being made by textile hubs in Punjab, Gujarat and South India, face shields are being made using 3D printing technology by companies like the Mahindra Group, 3Ding and Groundup Technology.

“Several medium and small manufacturing enterprises are working to refocus their capabilities to respond to the crises,” says Sinha. “We are working with several; some have repurposed their garment manufacturing lines to create PPEs and masks, while others are realigning their manufacturing capabilities to create ventilators.” For instance, AgVa Healthcare is partnering with Maruti Suzuki India, and Skanray Technologies with BEL to make ventilators. Detel, an electronic brand that makes budget mobile phones and televisions, has launched a sub-brand called DetelPro to make affordable PPE kits.

● Additional inputs from Naini Thaker

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)