Covid-19 puts Indian economy on the ventilator

The government is faced with the double task of keeping companies solvent during the lockdown and reviving consumer demand once it's over

A manufacturing plant of Maruti Suzuki India in Manesar, Haryana. On April 1, the carmaker reported a 47 percent drop in salesImage:Pradeep Gaur / Mint Via Getty Images

A manufacturing plant of Maruti Suzuki India in Manesar, Haryana. On April 1, the carmaker reported a 47 percent drop in salesImage:Pradeep Gaur / Mint Via Getty ImagesUnder usual circumstances, Maruti Suzuki India’s monthly auto sales numbers released on April 1 could have been mistaken as a April Fools’ joke. Sales were down by 47 percent over a year ago. Rival Volkswagen Passenger Cars India shipped a mere 131 cars, to register a 95 percent decline. Compare this to the last broad-based downturn in sales and Maruti had recorded its worst performance of a 20 percent decline in November 2008.

The recent decline underscores how badly demand and supply across the country have been hit because of the halt in economic activity due to the spread of coronavirus. The 21-day nationwide lockdown was announced only towards the end of the month, on March 25. “This is a very fickle situation and I estimate that 55 percent of the economy has shut down,” says Pronab Sen, former chief statistician of India.

As large companies like Maruti see demand falter, their suppliers who work on lower margins and tight working capital cycles may have to declare bankruptcy. While concrete numbers are awaited, anecdotal data points to a large-scale dislocation in economic activity.

Ecommerce companies are unable to ship orders across states, and consumer goods makers are struggling with shortages of packaging material and workers. It’s anybody’s guess how tepid consumer spending will be once the lockdown is lifted. Lenders fear that the large growth in retail and personal loans over the last five years is likely to result in a fresh problem of bad loans for banks and non-banking financial companies.

If India were to follow the same infection curve as Italy, Spain and the US, there is every indication that the shutdown activity could last, at least, till June. “The first half of FY21 would see a period of negative growth,” says Pranjul Bhandari, chief India economist, HSBC. “There has been a huge disruption in the labour market and it will make pushing the restart button harder.”

While the government has focussed on getting food to the poor and improving liquidity in the banking system, it has so far saved its firepower for later use as it grapples with the spread of the virus. A key part of the challenge will be to make sure smaller companies that may be technically insolvent are able to restart operations once the lockdown is over. For now, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code has changed the minimum threshold for filing for bankruptcy from ₹1 lakh to ₹1 crore.

Ratings agency Crisil has announced more downgrades (469) than upgrades (360) in the second half of FY20. Construction, gems and jewellery, and airlines are particularly vulnerable while the telecom, pharma and FMCG sectors are safe.

An important clue to the government’s thinking on the solvency of companies lay in the March 24 press conference by Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman where a host of regulatory deadlines were extended. “We are watchful of the situation and if the situation warrants, we may consider suspending Section 7, 9 and 10 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code,” she said, indicating that there could be wide-ranging stoppage of proceedings so that companies can get back to work and pay their debts in due course. “It is only once the supply side kicks in should the demand stimulus come. In the absence of that, we run the risk of any demand stimulus being inflationary,” says Sen.

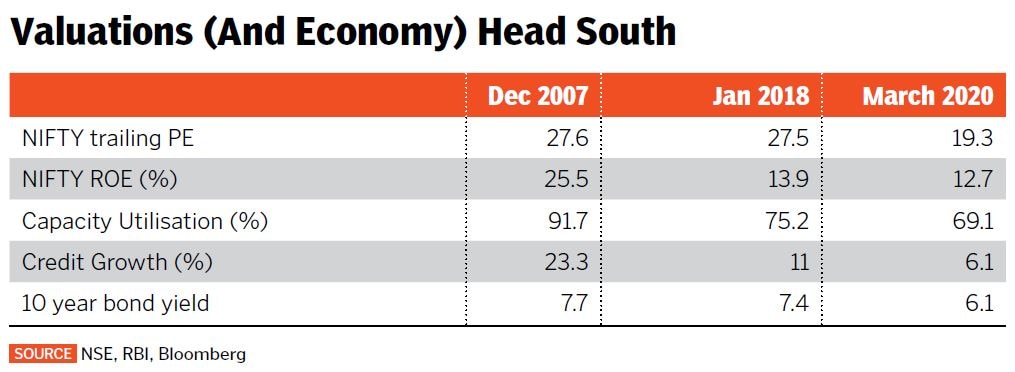

As the markets wait for the coronavirus impact to become clearer, investors have taken some money off the table. In March, the Sensex fell by 26 percent while the Nifty Midcap 100 fell by 29 percent. The India VIX (Volatility Index) has soared to levels last seen during the 2008 crisis. While the speed of the fall has caught investors by surprise, there is no indication to suggest that the worst may be over as the market is unable to discount future earnings potential due to the lockdown. As the value of credit is priced out of company valuations, those that have insufficient cash reserves and loans that are due have seen their values plummet.

“The present fiscal will be a washout in terms of growth. I can only hope that in the next fiscal, we stay on course as per earlier forecasts,” says Raamdeo Agrawal, chairman of Motilal Oswal. The International Monetary Fund estimates global growth at 1 percent in 2020.

The present fall has had a disproportionate impact on banks and financial services companies as investors price in the risk of loans going bad as well as lower interest rates that would compress their net interest margins. Private banks have also faced questions on the stickiness of their deposits, on account of the Yes Bank moratorium. Their inability to grow their liability franchise would hinder their ability to grow their loan book, thus choking credit to the economy. IndusInd Bank said it had seen an 11 percent reduction in deposits in the March quarter, while RBL Bank saw an 8 percent reduction.

For now, the duration of the lockdown is key to watch. India is still a month behind the Italy, Spain and the US infection curve. High infection and death rates coupled with salary cuts and job losses could impact consumer sentiment and spending negatively even when the lockdown is lifted. The result: An extended slump for discretionary spends pointing to an end to the consumer spending cycle that has powered growth for the last decade.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)