The view from Beijing

To solve the trade war, the United States may need to look at issues from China's point of view

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

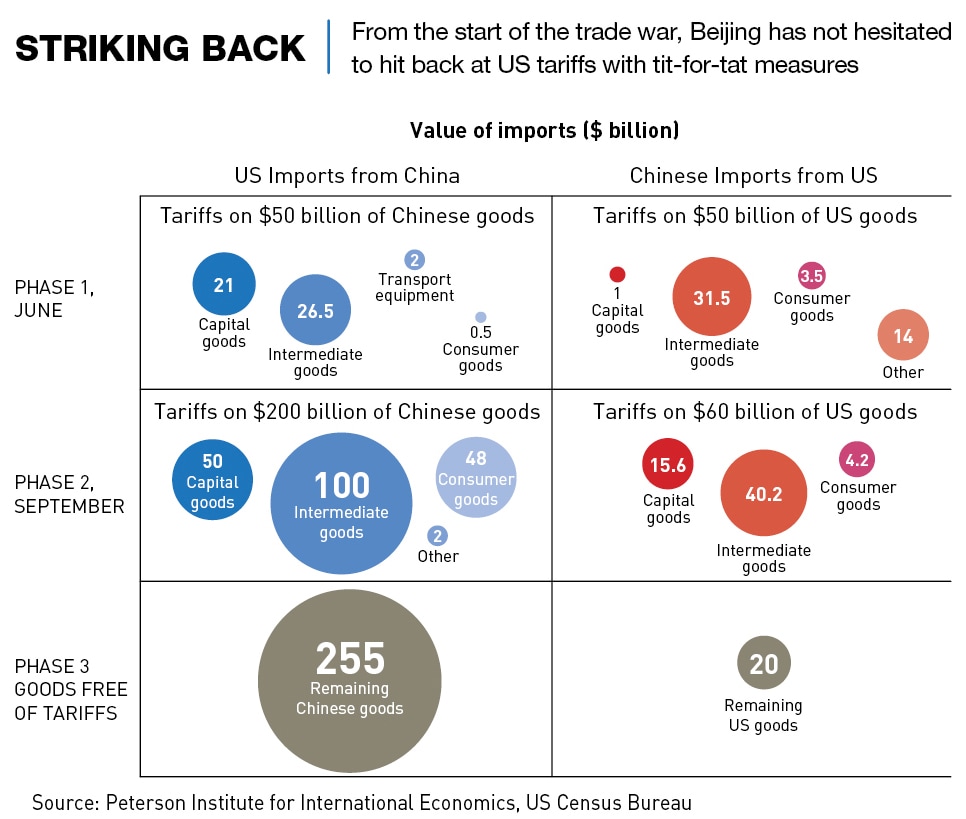

Some argue that US tariffs will force China to make large concessions on trade. But there is a risk that the growing pressure will make Beijing less, not more likely to compromise on key issues

President Xi Jinping set a hard tone for China’s intensifying trade war with the United States back in June when he met with a high-powered group of American and European executives in Beijing. The US had just threatened to impose tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods, and the Chinese leader warned his foreign guests that this action would have consequences.

“In the West, you have the notion that if somebody hits you on the cheek, you turn the other cheek,” Xi reportedly told the assembled CEOs. “In our culture, we push back.”

The message Xi was sending was clear. After decades of hiding its strength and biding its time, Beijing had decided to go toe-to-toe with Washington on issues it considered central to its interests.

In the months since, many analysts have been waiting for Beijing to abandon this hardball approach. As US tariffs began to inflict economic pain, Beijing would be forced to soften its stance to secure a much-needed end to the trade war.

The implementation of the $200 billion round of tariffs in September did accelerate China’s economic slowdown, though domestic factors were possibly more important. As winter rolled on, business sentiment plummeted, the stock market continued its precipitous decline, and exports, retail and property sales all took a hit.

However, there have been few signs of a change in Beijing’s negotiation tactics. According to Zhang Baohui, Director of the Centre for Asian Pacific Studies at Lingnan University in Hong Kong, Xi’s team is unwilling to make meaningful concessions on two issues in particular: the government’s support for large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and for high-tech companies in emerging industries through initiatives like the Made in China 2025 industrial strategy.

“The Chinese have said that they can make concessions. They will stop forcing American companies to transfer technologies, do better to restrain cyber theft and open more service sectors—these are not big deals for China,” says Zhang. “But they have stood firm on the most controversial issues.”

Several senior figures in the Trump administration, including US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, view forcing Beijing to cut back its preferential policies for SOEs and domestic high-tech firms as a key goal of the trade war. It was assumed that any deal to roll back tariffs would include Chinese pledges on these structural issues.

Yet, those expecting a Chinese climb-down have continually been disappointed. After a crunch meeting between Presidents Trump and Xi at the G-20 summit in Buenos Aires on December 1, both sides released statements summarizing discussions and the issues for further negotiation. Neither version mentioned SOE reform or Made in China 2025.

A few days later, Xi delivered a speech in the Great Hall of the People, which he was expected to use to unveil eye-catching reforms designed to address US concerns. Instead, he extoled the party’s achievements and declared, “no one can be the master (jiaoshiye) of the Chinese people.”

The US is sure to keep pressuring China to make changes on SOEs and Made in China 2025, which the country believes hands Chinese companies an unfair advantage. Lighthizer discussed China’s industrial strategy with Vice Premier Liu He during a call shortly after the G-20, the Wall Street Journal reported.

But reports that the Chinese leadership plans to abandon the policy appear wide of the mark. “Beijing does not talk about Made in China 2025 anymore, but things haven’t changed much on the ground,” one Chinese entrepreneur told Nikkei Asian Review in January. “I don’t think the government will ever pull back their support.”

An economic crisis or another escalation in the trade war could still force Beijing to backtrack, and Lighthizer may lobby to raise tariffs further for this reason. “If [Lighthizer] thinks he’s not going to get a good deal, he’ll be content keeping the tariffs on,” a senior lobbyist told the Financial Times in November.

But the theory that China can be pressured into abandoning centrally-controlled industrial policies may be a miscalculation. American discussions of the trade war have focused on the costs for China of not doing a deal, without considering how China weighs up the other side of the ledger.

Capitulating to Washington would have profound political consequences for the Chinese government. Ideology is a foundation of the party’s position, trumping all other issues.

On top of that, there is a long history, largely forgotten in the US but studied keenly in the corridors of Zhongnanhai, the leadership compound next to Tiananmen Square, informing China’s trade war strategy. And this history makes China cautious of acceding to US demands.

Japanese Lessons

For many in Beijing, the trade war confirms long-held suspicions that the United States is determined to thwart China’s rise as the world’s next superpower.

“More and more in China’s elite circle now think Trump’s trade war is not just about fair trade and trade balance,” Zhang told Bloomberg in September. “Rather, it is a containment program to change China’s long-term power trajectory.”

As a result, US demands that China abandon Made in China 2025 have tended to be viewed by Beijing as being motivated not by concerns over fair competition, but by a desire to make sure America keeps its lead in the global innovation race. Public statements from senior figures in the Trump administration have fueled these concerns.

“When I came [into office], we were heading in a certain direction that was going to allow China to be bigger than us in a very short period of time,” the president said at a West Virginia rally in August. “That’s not going to happen anymore.”

When asked last year whether the administration’s trade policy aimed to prevent China becoming a world leader in high-tech industries, Peter Navarro, Director of the White House National Trade Council, replied: “Exactly.”

Beijing views the trade war not as an isolated incident, but part of a longer history of US attempts to undermine rival powers. According to Richard McGregor, Senior Fellow at the Lowy Institute, China pays particular attention to the trade dispute between America and Japan in the 1980s.

“I know from talking to Chinese officials that they have studied the Japan-US example thoroughly,” says McGregor. “The Chinese saw the Plaza Accord as a deliberate effort by the Americans to hobble a competitor, and they’re determined that they won’t allow it to happen to them.”

The Plaza Accord was a 1985 agreement between Washington and Tokyo under which Japan promised to revalue its currency to lower its trade surplus with the US, a move that many argue created Japan’s bubble economy. “Most Japanese don’t see it like that,” points out McGregor. “But it’s like a catechism inside the People’s Bank of China.”

China and the US have largely moved on from arguments over the value of the RMB, but the distrust of American intentions lingers. Another lesson Beijing appears to have drawn from the Japan-US dispute is that capitulating to American demands simply embolden US negotiators to ask for even more.

As McGregor explains in his book Asia’s Reckoning, which charts the history of China-Japan-US relations, the Reagan administration pressured Tokyo for years to limit exports of semiconductors to the US market and buy more American chips. Japan eventually agreed to a deal guaranteeing US chip companies 20% of the Japanese market.

“While Japan insisted the deal was a one-off, the United States would later try to use the agreement as a template for demanding similar targets for market share of American goods in other sectors,” McGregor writes.

Comments from Chinese officials involved in negotiations with the US suggest that Beijing fears a similar situation today. “Will the US side keep coming back for more after we strike a deal?” one policymaker asked the Wall Street Journal in January.

The upshot is that Beijing may not see striking a deal with Washington as a way to gain relief from US pressure. Rather, it may see the cost of surrender as even higher than that of carrying on the fight.

As a result, if Washington wants to secure a lasting agreement with Beijing, it may first have to convince it that its intention is to protect a rules-based system, not undermine China’s long-term development, as many in China fear.

Escaping the Trap

This will be a tough sell on the issue of Made in China 2025, as Beijing considers this policy crucial to China’s future. There is an enormous gap between how China and the United States perceive the strategy, which aims to make China globally competitive in several high-tech industries.

American reporting on the policy often describes it as China’s plan to “dominate” the industries of the future. The Council on Foreign Relations, an influential Washington think tank, has described Made in China 2025 as a “real existential threat to US technological leadership.”

Lighthizer appeared to be alluding to this analysis when he commented in March: “There are things that if China dominates the world, it’s bad for America.”

For Beijing, by contrast, Made in China 2025 is considered the only way to counter an existential threat to its own economy: rising labor costs in the country’s manufacturing sector. Factory wages rose 64% between 2011 and 2016, according to Euromonitor. This is undermining the competitiveness of Chinese manufacturers, which have been the engine of China’s growth for decades and still generate nearly 30% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

These trends are of concern to Beijing because many countries have followed a similar growth trajectory to China in the past but ended up losing their economic dynamism and falling into what economists call the “middle-income trap.”

According to the World Bank, there were 101 economies considered middle-income in 1960, meaning that their per capita GDP was between $1,000 and $12,000. By 2008, only 13 of these economies had managed to achieve high-income status.

With a per capita GDP of $8,827 as of 2017, China is right at the most challenging stage in the development cycle. Failing to make the transition to a high-income economy is a real prospect.

“The top leadership is highly concerned about the middle-income trap,” says Zhang Jun, Dean of the School of Economics at Fudan University.

Making the transition to a high-income economy will need increasing productivity across all sectors, but also moving up the value chain to high-end manufacturing and technology. This is what Made in China 2025 is designed to achieve.

“Made in China 2025 is crucial to leading the Chinese economy out of the middle-income trap,” says Zhang. “You have to keep upgrading manufacturing over time.”

For this reason, China is unlikely ever to agree to roll back Made in China 2025 completely: the potential long-term economic costs are simply too high.

Finding Common Ground

The US is more likely to convince China to make changes to the strategy if it focuses talks on the technicalities of the policy, rather than China’s technological ambitions more generally.

“However this trade conflict ends, I don’t think it’s going to involve much of a climb-down by China from what it regards as its sovereign right to pursue the objectives laid out in Made in China 2025,” says George Magnus, former Chief Economist at UBS and author of Red Flags: Why Xi’s China Is in Jeopardy. “The two sides will have to agree on rules, perhaps with regard to industrial policy.”

Beijing will understandably point to examples of other major countries pursuing industrial policies, such as Germany, with its Industrie 4.0 plan for advanced manufacturing, to justify its use of a state-led development model.

But the US may be able to shift Made in China 2025 onto a more market-friendly trajectory. The trade war and the sudden economic slowdown have forced Beijing to rethink assumptions about its growth model, according to Zhang of Fudan University.

“The top leadership is reviewing the package of policies that was created over the past couple of years,” says Zhang. “They now specify that China should continue to make the system more open [to foreign competition] and to continue with structural reform.”

This may allow Washington to press Beijing to open Made in China 2025 for more participation by foreign companies. The strategy currently sets targets that 70% of core components in key technologies should be domestically-made by 2025, and the foreign business community has repeatedly complained that this is leading local governments to prevent overseas firms from bidding for contracts.

China’s large-scale government support for research and development and startups, however, is likely to be nonnegotiable. Beijing’s overall support for innovation is almost certain to increase, not decrease. The past year has driven home to Beijing, just as much as Washington, that relying too much on foreign technology could have national security implications.

In November, the US Department of Commerce revealed that it was considering trying to curb exports of a wide range of strategic technologies from fields including artificial intelligence, robotics, microprocessors and quantum computing.

If this policy became law, it would have profound consequences for the Chinese economy. China is still highly dependent on foreign technology in several areas. The country buys 27% of the world’s industrial robots and imports $260 billion of semiconductors per year.

Even the risk of a US export ban or other restrictions on China’s access to key technologies will force Beijing to accelerate the development of domestic technology firms.

“It’s quite obvious that the threat from the US will reinforce the commitment of the Chinese leadership to put more emphasis on domestic innovation,” says Zhang. “China would mobilize resources to support development work on several of the key technologies, including microchips.”

How Washington would react to remains to be seen. There will be those urging the White House to hit Beijing harder, in the hope of extracting further concessions. On this issue, however, the extra pressure may simply lead China to retreat further into its shell.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]