The Tap's Running Dry

India needs to work fast to save its rivers; otherwise the Ganga and Yamuna could soon pass into mythology

For India, China, Nepal and Bangladesh, the availability of water and dependence on the monsoon is central to the problem of food security. Huge tracts of farming regions in all four countries are fed by rivers that have a common source — the Himalayan glaciers. It is this common thread that now has India and its three neighbours facing a possibly much more serious food security crisis than the present one; something that can push inflation to levels that will make the present rate deem manageable.

This is one of the conclusions of the think tank Strategic Foresight Group in its to-be-launched study titled The Himalayan Challenge, Water Security in Emerging Asia. “We do not want to be alarmist. We are not saying that the glaciers will vanish in another 30 or 50 years. In fact, that might take up to 700 years. But the process of melting has started and the impact is starting to show,” says the group’s president, Sundeep Waslekar.

By 2050, says the study, a lethal mix of this glacial melting along with water scarcity and disruptive precipitation patterns will see a massive reduction in the production of rice, wheat, maize and fish. It predicts, “Both India and China will face drop in the yield of wheat and rice anywhere between 30-50 percent by 2050. At the same time, demand for food grains will go up by at least 20 percent. As a net result, China and India alone will need to import more than 200-300 million tonnes of wheat and rice, driving up the international prices of these commodities in the world market.”

Consider this. A weak monsoon last year triggered a minor food crisis in India. Though the country has surplus wheat and rice currently, it is a net importer of pulses and oil seeds. From time to time, India also depends on the international market to meet the local demand for sugar. The result of this mixed fortune in food security? A food inflation that has hovered around the15 percent mark for over a year.

The food security report among India’s neighbours is not rosy either. China is a net importer of palm, soya and is buying large amounts of corn from the US, in levels that were last seen 14 years ago. Bangladesh is importing 300,000 tonnes of its staple food, rice, this year and Nepal has been dependent on the international market for its food needs for sometime now.

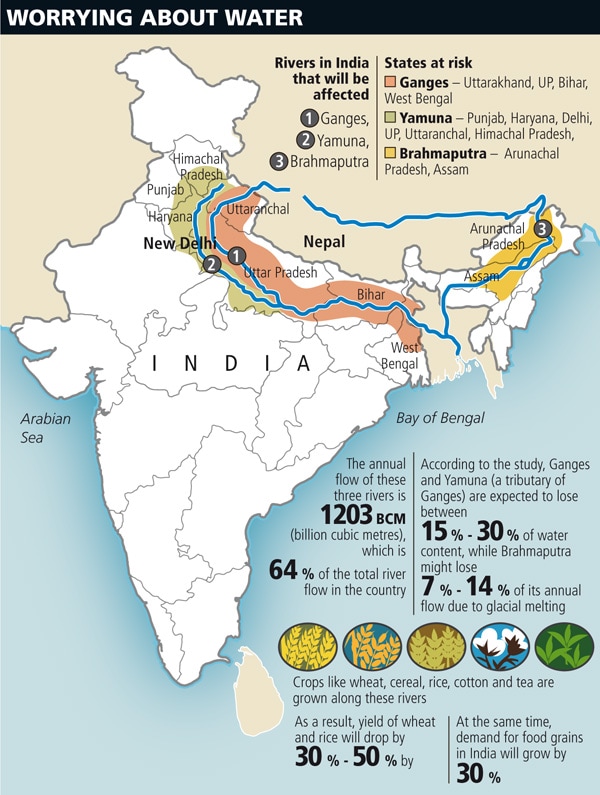

Illustation: Malay Karmakar

Put together, China and India are the largest producers and consumers of food grains and just a small variation in the demand and supply scenario is one country turns the global order topsy-turvy. For instance, if China were to import just 5 percent of its food grain needs, then the whole global export will be eaten up. In a similar situation, sugar deficit in India last year drove the sugar futures in New York to a 29-year high. The Yellow River in China and the Ganges (with its tributaries) in India will be the most affected by glacial melting and might turn into seasonal rivers by the second half of the century, the study notes. “They are expected to lose between 15 percent to 30 percent water due to glacier depletion. The Yangtze and Brahmaputra will also lose about 7 percent to 14 percent of the annual flow due to depletion of glaciers. Bangladesh will face the cumulative impact of these developments,” it says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)