Shale We Drill?

Reliance Industries bet on American shale gas has opened our eyes to the potential that exists right in our backyard

For almost a year now, and especially after the aborted acquisition of chemical giant LyondellBasell, the energy market has been waiting for Reliance Industries to make its next move. Sitting on almost $6 billion in cash, India’s largest company by value has been prowling around the world for lucrative opportunities. The company finally made its wager in April. The bet was placed thousands of miles away in south-eastern United States, on a sandstone rock formation called Devonian shale.

The $3-billion-plus bet on shale gas in two joint ventures signed up since, is RIL’s largest overseas investment ever. Like the gas it seeks to find, the move is unconventional, not the least by the company’s own yardstick. RIL has paid for a minority stake in two companies — 45 percent each in Atlas Energy’s Marcellus lease and in Pioneer Natural Resources’ core Eagle Ford acerage. Not only are the investments being made without majority control of the companies, they are also in a market that RIL has little presence and virtually no influence over. Neither does RIL have any knowledge of the terrain’s geology. And therein lies the key.

Illustration: Minal Shetty

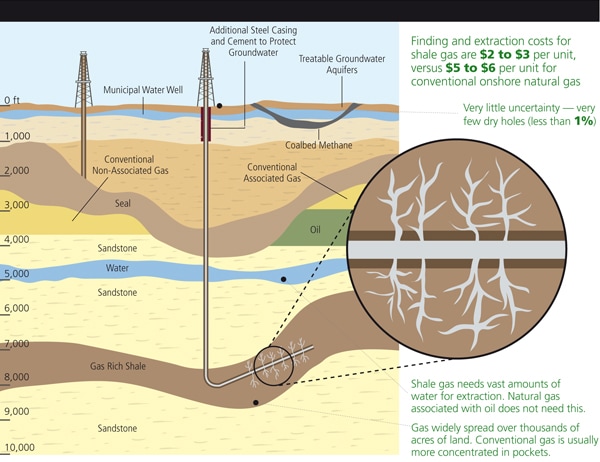

At the core of the shale story is the stunning progress in the technology used to extract the gas from ‘tight’ rocks, through a process of hydraulic fracturing. This involves bombarding the rocks with millions of litres of chemically treated water to force the gas to flow. Shale gas is no different from the regular natural gas (primarily methane), and its presence over a wide area of thousands of acres has been known for years. But it was not pursued vigorously due to the difficulties of extracting it.

The breakthrough came when a bunch of medium-sized oil companies figured out smarter ways of drilling in the last three years. As technology improved, the recoverable reserves were quickly upgraded. In the Marcellus basin in Pennsylvania for instance, reserves grew from 15 tcf (trillion cubic feet) five years ago to 270 tcf now. Little-known, medium-sized companies like XTO, Devon Energy and Pioneer Natural control the technology and process of extraction. Many are being snapped up by big oil companies who have realised that they cannot afford to be left out of this game. XTO, for instance, was picked up by Exxon-Mobil for a whopping $31 billion deal that was approved by shareholders in June. Other under-capitalised companies are going for joint ventures with foreign companies with deep pockets like BP, Total and most recently RIL.