India's Wheat Dilemma

Traders and economists are divided on the impact on India of the surge in global wheat prices

The world grain markets are in a tizzy. The decision of Russia to ban export of wheat has caused the prices of this grain to soar 60 percent above normal levels. By mid-August, wheat prices had already reached $7.13 a bushel, or $264 a tonne. These prices could climb further as the extent of the flood disaster in Pakistan and China begins to seep in. Pakistan’s wheat bowl in Punjab has been totally devastated by the floods. And some of China’s farmlands too have got inundated.

Infographic: Hemal Sheth

But what about India, which is a large wheat consumer? The good news is the impact will not be significant due to at least two factors.

First, a large portion of the wheat that India grows is sorely dependent on the rains. This year the rains have been good, and there are chances that wheat production will be higher than the levels of the last five years, despite stagnant yields.

Minimum Support Prices (MSP) set by the government form the floor for domestic wheat prices in India. MSPs for wheat have been raised from Rs. 640 per quintal to Rs. 1,100 currently. Grain subsidy and pricing policies have resulted in low correlation of wheat prices to headline inflation. Thus, higher global wheat prices are unlikely to have a major impact on domestic prices.

In fact, at the current support prices, India’s wheat is already priced at $330 a tonne. With global prices currently at under $265 a tonne, global developments are unlikely to adversely affect India.

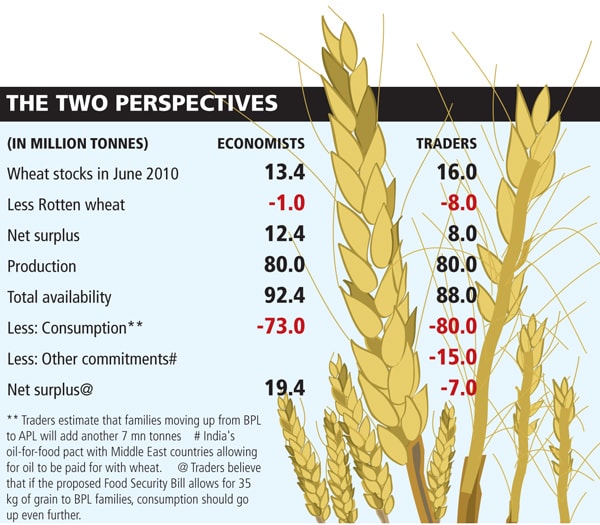

That said, there is one big joker in the pack. It is the size of India’s surplus wheat stocks or a lack thereof. Depending upon who you speak to — the trader or the economist — you either get a deficit or a surplus.

Kushal Thaker, a leading commodity trader and consultant, says, “According to our calculations, there is a wheat shortage that could hit India by January next year.” Many other traders agree with him.

However, eminent economists like Ashok Gulati, director at International Food Policy Research Institute, disagree. “India has huge wheat stocks. So does China. If India and China open their borders, the world’s crisis can be easily overcome. If India wants to play a responsible role in the world, it should immediately export 5 million tonnes of wheat that is lying rotting without protection, and that will cool global prices.”

So who’s right? There are a few more variables that will dictate the answers.

Few people know of the Indian government’s oil-for-wheat treaty with Oman, Dubai, Qatar and Saudi Arabia where the oil it gets is swapped for wheat to aid the domestic consumption in those countries. This treaty kicks in when oil prices are over $70 a barrel. The traders figure this could account for approximately 15 million tonnes. Gulati, on the other hand, doesn’t think the impact of this treaty will be that severe.

Another variable is the upcoming Food Security Bill which will increase the demand for wheat substantially. Also, any reduction in China’s wheat production, as predicted in some quarters, could further push up global wheat prices further.

Given that in a tight situation as the one that exists in wheat globally, it would be wise to watch the change in margins of these variables. One gets the feeling this chapatti is not fully cooked as yet.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)