How Much Benefit Does That Costly Cardiac Drug Hold?

Newer, expensive drugs for cardiac care may be only marginally more effective, but are prescribed aggressively. India needs strong prescription guidelines to keep treatment costs in check

The debate over food prices is one that has consumed many of us for a while now. But there’s one debate that is missing from public discourse: The rising cost of healthcare, which has steadily climbed 12 percent to 14 percent annually over the last decade, according to the National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health.

According to the World Health Organization, one in 10 Indians is expected to suffer from some form of cardiac disease by 2020. Cardiac ailments will also account for a third of all deaths in the country.

India is set to lose 17.9 million years of life, among people below 60 years, to coronary heart disease by 2030. “More life years will be lost as a result of this disease in India than is projected for China, Russia and the United States combined,” researchers wrote in a series of papers in the medical journal The Lancet in January.

In late January, two medical associations raised red flags about the spiralling costs of cardiac care. The American Heart Association — more than 80 percent of whose guidelines are followed by cardiologists in India — announced that costs in the US will triple by 2030 to $818 billion a year.

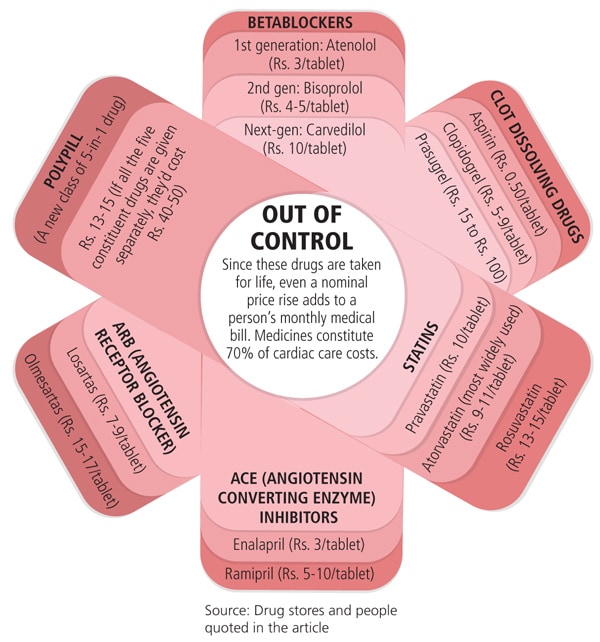

An analysis in the Canadian Medical Association Journal said cardiac care costs in Canada had increased 200 percent between 1996 and 2006, with one particular drug, ARB (angiotensin receptor blocker), witnessing a 4,000 percent increase in use.

The association has suggested a policy of restricted access to ARB, which is marginally better than its cheaper alternative ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitors.

In comparison, the Cardiological Society of India (CSI) looks like a poor cousin with no control over the rising costs of healthcare and no policy document or guidelines for doctors on what drugs and treatment to prescribe.

Outgoing CSI president Dr. Samuel K. Mathew, Apollo Hospital, Chennai, says there is a lack of guidelines because the Society does not have statutory powers, unlike its Western counterparts. Framing guidelines is a “waste of time”, he says, because they can’t be enforced. “In the past, we have given so many guidelines, but nobody follows them. All powers rest with the Union health minister, and he isn’t accountable to anyone.”

In cardiac care, medication and procedures account for 70 percent and 30 percent of the cost, respectively. While surgery costs have gone up about 30 percent in the past five years, according to market research firm Deloitte, it’s the cost of life-long medication that could actually take a heavy toll on patients.

“Doctors are swayed by the hard sell of drug companies. Newer drugs may be only marginally [more] effective, with very little data on Indian population to support them. Yet they are prescribed aggressively. The Canadian observation on ARB and ACE inhibitors applies to India as well,” says Dr. Ashok Seth, president elect of CSI and chairman and chief cardiologist of Fortis Escorts Heart Institute in New Delhi.

Seth is worried that, like ARB, Prasugrel, the latest clot buster in the market, might find easy access to patients and start competing with existing cheaper alternatives. “General physicians need to be educated about its defined role,” he says.

The same is true for betablockers, calcium blockers or statins, says Dr. Ramakanta Panda, managing director, Asian Heart Institute, Mumbai. He says a recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that non-medicated stents are almost as effective as medicated stents. “But the cost difference [in India] is about Rs. 80,000. So doctors should think hard before using it because it’s needed only in a small number of cases,” he suggests.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

But, in the absence of guidelines, there is no regulation on the prescription of more expensive, but only marginally more effective, drugs and treatment.

K. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, says, “If you leave these things to practicing doctors, it will be based on clinical effectiveness, not on cost-effectiveness.” But a small difference in clinical effectiveness may translate into a big difference in costs for the patient.

Reddy is heading an expert committee that was constituted by the Planning Commission in October to provide direction to universal health coverage in India. He is proposing an Integrated National Health System with “some kind of price fixation, drug regulation, therapy guidelines and insurance coverage”.

“We need to figure out if insurance is as good as it is made out to be or if subsidised healthcare for 10 to 15 years is the answer,” says K.N. Desiraju, additional secretary, ministry of health and family welfare.

Desiraju hopes that the committee’s findings will be implemented in the 12th Plan. The committee will submit its report in June.

Insurance coverage, however, may fuel rising costs of cardiac care. In cardiology, costs are relatively contained as penetration of insurance is low. But an increase in insurance cover might mean that patients become less concerned about bearing the cost themselves and therefore be less bothered about opting for cheaper alternatives in medication and treatment.

Once insurance cover increases, costs will rise, says Charu Sehgal of market research firm Deloitte Touche Tomatsu.

But whatever direction the government may decide on, it is somewhat obligated — as part of United Nations requirements — to come up with a national policy on chronic diseases before the special UN General Assembly Summit on non-communicable diseases in September.

For Seth, the solution lies in raising awareness and prevention. “It has to stare you in your face every day,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)