CSIR Goes For A New Patenting Model

India's premier science council has realised the Western model of patenting doesn't work here

When the National Chemical Laboratory in Pune, one of the 37 labs under the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), licensed its polycarbonates technology to General Electric in the early 1990s, its chief executive Jack Welch is said to have remarked, “If they are so good, why are we not there?” The conglomerate came soon after, setting up its largest research centre outside the US in Bangalore.

Since then, particularly under its former director R.A. Mashelkar, CSIR took to intellectual property (IP) protection rather aggressively. It closely followed Western university models, even drawing criticism along the way that it spent more on patent filing than earning from it. About two decades later, with a few hits and misses under its belt, CSIR says it has finally figured that the industry-centric IP licensing model of the West can’t be replicated in India.

“Everything is not commerce. I am asking [for] a new developmental model which is people-centric,” says CSIR’s current director general, Samir Brahmachari. In a globalised world, when IP is held in one country, the product is designed in another, and manufactured and sold in some other countries, it’s difficult to gauge the true value of IP that also includes public welfare, he says.

As a result, CSIR will now follow a three tiered licensing approach.

For high-value technology that requires niche expertise, it’ll go for the kill. Like it did with the Institute of Microbial Technology’s next-generation clot dissolving drug — recently licensed to US-based Nostrum Pharmaceuticals for $150 million. For another category, where national interest is involved, it’ll co-invest with the industry to commercialise it. Like it is doing with Tata Chemicals in Bhavnagar, Gujarat, for producing marine-derived potash, which could result in import substitution worth Rs. 8,000 crore for the fertiliser ministry. Then there are technologies that are low on invention but high on social impact. CSIR will license these for a notional fee — like it has done with the solar-powered pedal-operated cycle rickshaw. It’s been licensed to the Kinetic Group, which will soon start mass production for postmen and dairy vendors.

“If Brahmachari’s perspective is that universities should license inventions for low royalties in some cases, focusing on improving welfare rather than generating revenues, this is welcome news,” says Bhaven Sampat, professor at Columbia University, who has extensively studied university research and patenting. Indeed, in some cases the best form of ‘technology transfer’ could be to eschew patents and licences altogether and place the research results in the public domain, he says.

If you look at patenting from a global angle, says Mashelkar (now president of Global Research Alliance), NGOs take one extreme view, companies take another. “We have to have a middle path for the society to benefit,” he says. “In what CSIR is now attempting, India can teach a new model to

the world.”

Globally, university licensing underwent a transformation after the passage of the US Bayh-Dole Act in 1980. American universities intensified marketing of faculty inventions as this Act allowed them to exclusively license IP to the industry. Academic institutions in other countries followed in America’s footsteps. CSIR was no different. In late 2009 it invited a US-based professional to lead CSIR-Tech, a loosely formed entity with the mandate to commercialise CSIR IP. That ad-hoc appointment ended in a fiasco, with both sides claiming a mismatch of goals, systems and processes.

Now CSIR is finalising another concept — CSIR Ventures, a non-profit that will sell/license IP on CSIR’s behalf and raise a corpus to incubate companies. Brahmachari says some financial institutions, including SBI Market Cap, have evinced interest in investing.

CSIR Ventures is being modelled on Cambridge University’s tech licensing arm, Cambridge Enterprise, which manages 800 active IP, licensing and equity contracts while working with 1,000 academics. Incidentally, says its chief executive Teri F. Willey, Cambridge Enterprise is itself modelled on Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s licensing system.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

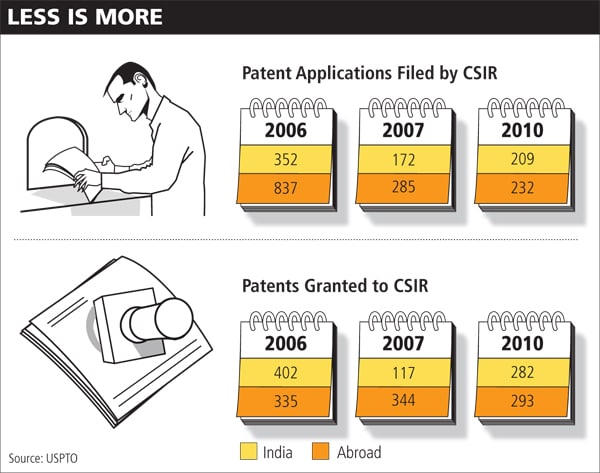

Even as this experimentation is underway, CSIR, since Brahmachari took over in 2007, has become more selective in patent filing. “In the last eight years our lab got 50 US patents but in the 12th Plan we’ll focus on commercialising them,” says Pushpito Ghosh, director of Central Salt & Marine Chemicals Research Institute (CSMCRI) in Bhavnagar. In the process, he says, labs will now go a step further in setting up demonstration units as industry everywhere demands “usable” technology. To begin with, CSMCRI has set up a 0.75 tonne/day plant within its campus to manufacture potash using its own technology which is being licensed to Tata Chemicals. The latter is setting up another 3 tonne/day plant (to be scaled up later) where the department of science and technology will bear 70 percent of the equipment cost.

Similarly, CSMCRI is setting up a 2,000 square metre reverse osmosis membrane manufacturing unit (for desalination of sea water) in its campus. “We’ve licensed this technology to smaller companies, but to attract big customers, we need to demonstrate scale.”

As institutions seek their balance, they need to be careful about assertions that Western universities have been generating significant revenue from IP. “Some have, but many — probably most — don’t,” says Sampat. He says there is a growing concern in the US that the focus on university IP as a source of revenues is mistaken, because, one, the focus on licensing revenues may not be the best way to promote social returns; two, licensing IP is unlikely to generate much income.

Brahmachari couldn’t agree more. He is now seeking a Cabinet nod to transfer some formulations on infectious diseases from government’s Traditional Knowledge Digital Library into the Open Source Drug Discovery programme that he started three years ago. This could create new IP. “I am now going to give processes to garage companies to build products, let the Piramals and the Ranbaxys get bought [by multinationals].”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)