Are Direct Cash Subsidies Better?

Giving cash directly to the people was always a better idea than the convoluted subsidy system. But its time has come just now

After dithering on the matter for more than a decade, the government has announced that it will provide direct cash subsidy for fertiliser, kerosene and LPG. It will start by running a pilot based on the recommendations of a task force formed for this purpose, and headed by Nandan Nilekani. It is due to submit its report by June this year. The move is significant since many believe that once implemented, it will pave the way for similar direct cash transfers by the government in subsidies like food and education.

India spends about Rs. 160,000 crore every year or roughly two percent of the country’s GDP on subsidies, all indirectly. For example, in fertilisers — which accounts for two thirds of total subsidies — the government fixes a low selling price and compensates the producers by paying the difference between the selling price and the actual production costs (plus a pre-decided profit margin) as subsidy.

The indirect subsidy has been blamed for benefiting big farmers more than the small and medium farmers, for whom the subsidy is intended. This is because bulk of the subsidised fertiliser is picked up by the rich farmers because the small and marginal farmers account for just 37 percent of the farm land. Indirect subsidy has also discouraged improvements in production processes since manufacturers have no incentive to increase efficiency.

The same argument can be extended to other segments, such as primary education. A recent report on the status of schools by Pratham, a non-government organisation that works in the education sector, paints a dismal picture of the sector. There is high teacher absenteeism and low standards of education. For many state-run schools, there is no incentive to improve, since funds come from the government, and there is little pressure from students.

Moreover, so far there has been no reliable system in place to identify and target the people who are most in need of subsidy. But with systems like the Unique Identity Number in place, it might be possible to get the benefit directly to the deserving and leave out unintended beneficiaries. This will also play a big part in bringing down India’s overall subsidy bill. For instance, according to industry estimates, the money spent on poor farmers could potentially come down to Rs. 37,000 crore from the current Rs. 100,000 crore.

There are multiple options to give direct subsidies — through food coupons, school vouchers and direct transfer of cash to beneficiaries’ bank accounts. The complexity is not so much in the transfer of funds, as it is in the identification of the beneficiaries.

Another advantage of cash subsidies is that it will free up the distribution system and allow the people who receive the subsidy to choose where they buy their goods from.

Other Countries

The idea of directly giving money to the poor is becoming popular among the development thinkers and policy makers. It’s already a part of policy in many parts of the world: Predominantly in Latin America where 16 countries have this practice, and also in other countries such as Jamaica, Philippines, Turkey and Indonesia.

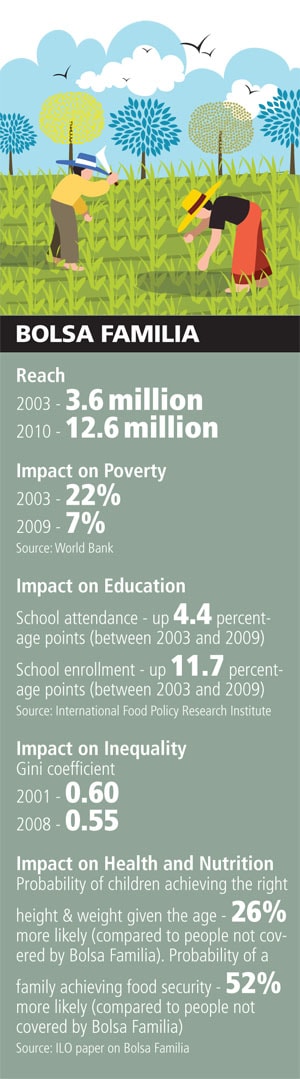

The biggest and most cited of such programmes is Brazil’s Bolsa Familia. It started in 2001, with a programme aimed at education. It expanded in 2003 to include a range of services like food and fuel and now covers 2.6 million families in that country. The government transfers cash straight to a family, subject to conditions such as school attendance, nutritional monitoring, pre-natal and post-natal tests.

By many measures, the programme is a success. Brazil’s poverty levels dropped by 15 percentage points between 2003 and 2009, at least a sixth, thanks to Bolsa Familia. (Economic growth played a big part too.) School attendance and enrollments went up; children were healthier; and inequality came down — the income of the poor grew seven times faster than the income of the rich. Millenium Development Goals initiative, which in 2000 sought to halve poverty by 2015, doesn’t even mention cash transfers. But, Brazil achieved the goals 10 years ahead of the deadline. And the cost of these transfers: 0.4 percent of GDP.

Practical Problems

This success explains why cash transfers have become popular among the policy makers in India. Yet, it would be a folly to think of it as a magic bullet to cure poverty, or even that it would have the same results as it had in Brazil.

Even in Brazil, the impact of the programme has been more effective in rural areas than in urban areas, where Bolsa Familia replaced some of the existing anti-poverty measures.

Besides, giving cash to people will not help when the problem lies elsewhere in the supply of services. A UNESCO survey found that while cash transfers increased school enrollments, it had no impact on learning itself when the school lacked proper instruction materials and support infrastructure. Similarly with health services; transferring cash to the poor will not help, when there are no health centres.

Even in the rather limited sectors that India plans to roll out direct subsidies, there are other practical issues. For example, Jayati Ghosh, professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, wonders how the government will be able to effectively subsidise the poor for fertiliser or kerosene once the prices are market determined and are liable to fluctuate.

“The government is trying to apply a technocratic solution to what is a socio-political problem,” says Ghosh alluding to the many informal power equations in the Indian society that work against the already disadvantaged sections of the population.

The path ahead will be rife with other practical difficulties. Identifying and including the poor, excluding the well off, plugging the leakages and making sure it has the desired impact will not be easy. But other initiatives, like the Aadhaar project and government efforts to make banking more inclusive, will help. It is significant that Nandan Nilekani, who is heading the Aadhaar project, has also been asked to head the task force on direct cash transfers.

The big question is not whether a direct cash transfer is the perfect solution, but whether it’s an improvement over the existing systems. The evidence — its success in other parts of the world, and the poor performance of indirect subsidies so far — would suggest so.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)