The Government's Mission for a Rainy Day

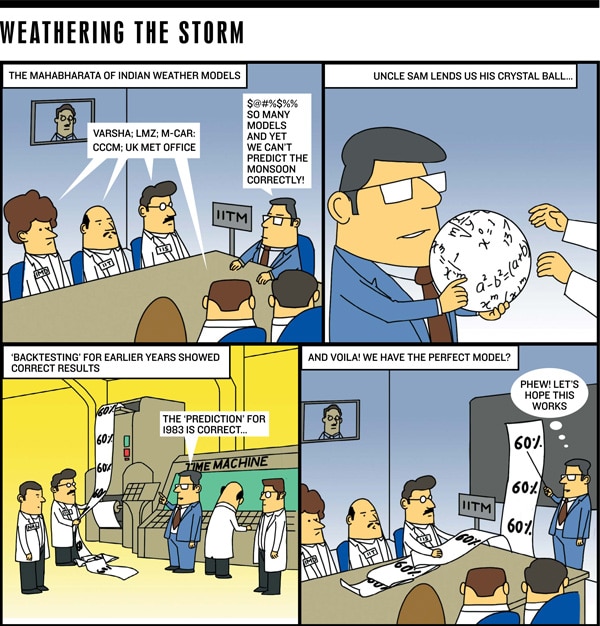

Will a single model help climate scientists make accurate predictions?

Nobody likes a bad monsoon, especially the government. Every time the monsoon fails, the country’s GDP goes down by 2-3 percent. The least the government wants to know is what the year’s rainfall is going to look like — something that has eluded meteorological departments across the country for decades. Now it seems the government has had enough. This August, the Ministry of Earth Sciences commissioned the National Monsoon Mission programme. It intends to spend about Rs. 400 crore to get the monsoon forecast right. The beauty of the idea lies in its simplicity: Get everybody together.

“Quite clearly there is a lack of focus and duplication of work. So what the mission states is that for long-range forecast, which is 15 days to three months, scientists have to work together on one model,” says M. Rajeevan, scientist at the National Atmospheric Research Laboratory.

It all started with the 2009 monsoon showers. Almost every weather prediction body in the country had forecast normal rainfall. The rain gods, however, decided to play truant and India recorded the third worst monsoon in a century.

What followed was a long period of introspection. At present, there are 10 bodies in India that work on monsoon forecasting. Each institute has its own forecasting model. A model is a set of equations in which you enter observations or data of several variables, and get a forecast. These variables are conditions in the atmosphere, oceans and clouds, among other things. And none of these models have been developed in India. They are borrowed from the US and European countries.

As expected, when these institutes came together for introspection after the 2009 debacle, they defended their models and gave several reasons why the forecast had gone awry. “It was like sitting in one corner and talking in the air,” says B.N. Goswami (61), director of Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM).

The monsoon mission seeks to eliminate this behaviour. The mandate of getting everybody together under one umbrella has been given to Goswami. He has played a crucial role in planning every detail and getting the project sanctioned from the ministry. The chosen prediction model is the National Centers for Environment Prediction-Climate Forecast System (NCEP-CFS).

But why choose Goswami and, more importantly, why the NCEP-CFS model?

For starters, the CFS is a model developed in the US with a success rate of about 60 percent in predicting the monsoon. It is another matter that European countries won’t give India the source code of their prediction models, because of which the success rates of these models are not known. “Without the source code you can’t change anything on the model. The US is willing to share the model with us,” adds Rajeevan.

Goswami’s role comes in because IITM used the NCEP-CFS model to predict the 2011 monsoon. In the past 18 months, the institute has extensively tested the model using a method called ‘hindcast’ to check if it can successfully ‘predict’ the amount of rainfall in a past year. For instance, IITM has fed in data from past years and compared the model’s results with actual rainfall from the period 1982-2009 and found it to be 60 percent accurate. However, issues creep in when making predictions for the future, essentially long-range forecast.

Take, for instance, IITM’s forecast for the 2011 monsoon. The institute has predicted the monsoon to be about 15 percent above normal. Though the monsoon is still on, this prediction is quite off the mark from the actual rainfall received so far. Goswami explains the variation, saying he “needs more skill in understanding the variables that go into the model and more importantly observation data”. Put simply, there are several variables in this model that need improvement, such as climatic conditions over the Tibetan plateau or cloud cover. By itself, IITM does not have experts in each of these areas.

However, there are experts in other institutes who work on weather forecast, such as the Indian Institute of Science, and the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. This is why the monsoon mission wants all these experts to come together and help improve this one model.

The request for research proposals was sent out by IITM in August. But getting all the institutes on board will not be easy.

To begin with, a few scientists believe that it is a question of their independence and privacy of research. Then, there is the question over compensation and research fellowships.

Quite a few scientists agree that the idea is good, but they don’t expect miracles. “My apprehension is that while the effort is good, a work plan is not there,” says Dev Raj Sikka, a renowned climate scientist.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)