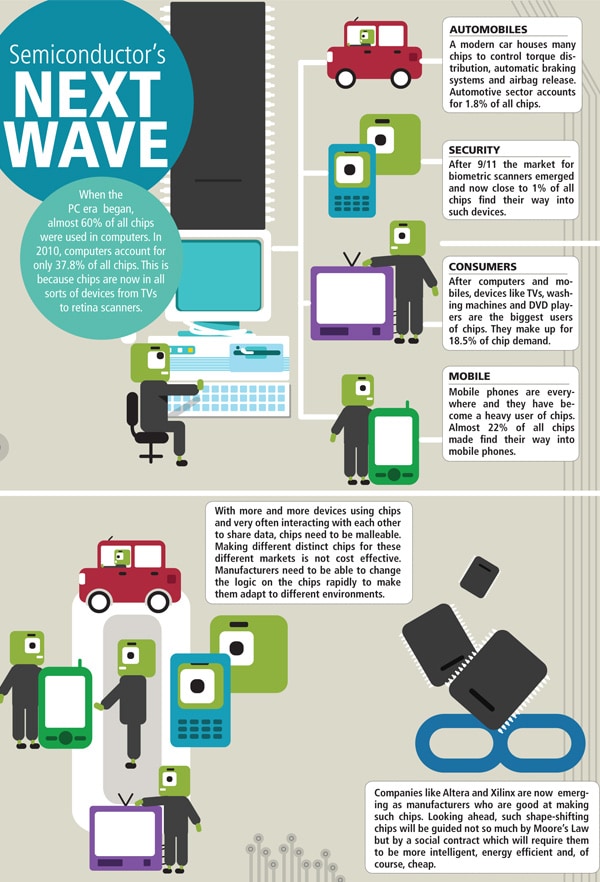

Semiconductor's Next Wave

It's about enabling different applications on the chip and providing a platform for the developer community to build apps on

It all started with Apple and its iPhone app store. Soon almost all electronic devices, from handhelds to car infotainment sets to airplane landing systems, took to application frenzy. Even governments now have app stores peddling public services-related mobile applications.

Consumers are charmed; so are app developers and device makers, as a steady stream of revenue trickles in. But in this flurry, the semiconductor industry, with margins being chipped away as they struggle to improve processor performance for enabling new applications, is staring at an inflexion point.

In the mid 1990s, chipmakers opted for a tech-lite model, choosing to outsource the tools for designing and engineering the processors. That widened the road for the electronic design automation industry. Towards early 2000, that business model gave way to a fab-lite era where many chipmakers opted to outsource chip fabrication.

Infographics: Sameer Pawar

Now, an application shift has taken effect. That means, among other things, your smartphone will soon be able to lock or unlock your car, and run its infotainment system which can even send a text message to a public or private agency if the car meets with an accident. That central console in your car could well become the nerve centre of “smart” driving. So far, standard semiconductor makers like Intel have chipped in with broader hardware and software solutions, complemented by tool makers like Cadence Design Systems who provide verification systems to ensure that as more applications get loaded on the infotainment unit, safety doesn’t get compromised.

More such collaboration is needed if the $300 billion semiconductor industry has to survive the single digit growth and improve its margins, says John Bruggeman, chief marketing officer of Cadence. It needs to move to a design-lite model where chipmakers leverage partners to get more chips to the market each year but at a lower cost.

“Design-lite simply means that the point at which the two companies collaborate will be flexible and as a result, some chips in a product line can be built largely by silicon engineering firms,” says Taher Madraswala, vice-president, engineering at Open Silicon, an Application-specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) company. In mid-November, Open Silicon tapped out 2.4 GHz, the fastest processor in its class, improving the earlier industry benchmark of 2.0 GHz. The chip, designed and developed largely in Bangalore, is being rolled out by California-based embedded semiconductor company MIPS Technologies. It will find its way into Web-connected flat panel TVs, set top boxes, Blu-ray DVD players and related consumer devices.

Users consider ASIC integrated processors too slow for the market, says Madraswala. As new performance levels are reached, the processor can take on the workload of new market segments. For example, a 500 MHz processor today might be a good fit for a multi-function printer, but a 1.6 GHz processor might offer state-of-the-art performance in a smartphone or tablet PC.

In a bold move, Cadence’s Bruggeman proposes to turn the chip-making paradigm upside down. “Think of applications first and then go all the way down to your software and hardware,” he argues. “It’s a software-driven world and India is at the heart of this change, moving towards the sweet-spot of skill sets.”

It’s no longer about the number of transistors you have on the chip or the features you have managed to cram in. “It’s about enabling different applications and providing the hooks to the larger developer community to build apps on. One company cannot do it all, and there needs to be a mindset to open platforms, industry standards and tools for the ecosystem to pitch in and provide creative applications,” says Neeraj Varma, country manager-sales, India, Xilinx. The company makes programmable processors or programmable logic devices (PLDs). Xilinx is part of the silicon tribe that has high operating margins at a time when standard semiconductor makers have nil to negative margins and are struggling to keep pace with the demand for applications.

Processors now need to be malleable. Think of an endoscope camera head where a doctor would want to use different cameras, reduce noise, or enhance colour as he looks inside the human body. Here, we are talking about the applications the silicon now enables. “We have to provide near complete solutions to customers either on our own or through our ecosystem of alliance program members,” says Varma.

After two years of decline, says research firm Gartner, the semicon industry is slated for a thumping 31.5 percent growth in 2010. Ironically, the rejoicing won’t last long. Gartner estimates the industry to grow barely 4.5 percent in 2011.

These trends indicate that it’s not enough to just have a strong balance sheet in order to succeed in the post-downturn era, says Jagdish Rebello, senior director and principal analyst, communications and consumer electronics, iSuppli Corporation. That somewhat explains Intel’s first ever lending of its fabrication facility to PLD maker Achronix Semiconductor Corp., or acquiring Europe’s biggest chipmaker Infineon’s wireless business earlier this year. Or, even its November acquisition of a Canadian digital signage start-up in its attempt to move out of its core area to create more niche products and go to market much faster.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)