Indian Telecom Operators' Bundle of Joy

Packaging subsidised handsets could be mobile operators ticket to profitability

College students around the world know the meaning of the acronym ‘BYOB’. Often accompanying party invitations, it tells the person being invited to ‘Bring Your Own Booze’.

Indian mobile operators have been practicing a variant with their customers, BYOH, or ‘Bring Your Own Handset’. Indian operators have mostly remained wary of subsidising and bundling handsets since the spectacular failure (following what appeared to be a spectacular success)

of Reliance Infocom’s 2003 ‘Monsoon Hungama’ offer.

During this offer, Reliance Infocom rapidly added millions of new subscribers on the back of dramatically discounted handsets. Hundreds of thousands around the country got themselves new mobile handsets nearly free of cost though they had no intention of ever paying a bill.

Thanks to outright identity fraud and a creaking legal system, there was no way Reliance could do anything about it. (However, many experts believe Reliance was fully aware of that, and wanted to merely attract as many subscribers as possible to break through regulatory barriers).

Wiser from the experience, mobile operators decided to stay mostly clear of subsidising handsets, even moving to a model where there was no need to trust a customer: Pre-paid.

But things might be changing.

In March, mobile operator MTS launched a fairly high-end Android smartphone — the HTC Pulse — for the grand price of zero. The catch? Commit to a minimum monthly rental of Rs. 1,500 for a year.

Then, a few weeks ago, Airtel and Aircel both ‘launched’ the Apple iPhone 4 in India (Apple launched it in the US in June 2010), bundled with ‘reverse subsidy’ plans by which the customer could make back almost the entire cost of the handset over time.

Though it’s still early days, this could signal a deliberate shift for operators away from the quarter-on-quarter race for subscribers towards more profitable and longer-term customers. This is significant because most operators are chasing marginal customers who will be loss-making in the future.

“Contractual value is much better than mere transactions. That is a significant shift in our business,” says Leonid Musatov, the head of sales and marketing for MTS India.

Unlike the disastrous Monsoon Hungama offer, operators this time are using subsidies to earn money, not to lose it. Take for instance the HTC Pulse that MTS offers free with a year’s plan. Though its MRP is about Rs. 16,000, its cost to MTS is likely to be at least 25 percent less, thanks to bulk discounts from the phone maker and the ‘channel profit margin’ that phone makers reserve for distributors and retailers, which in this case, comes to MTS. Therefore the “free phone” will cost MTS, at the most, Rs. 12,000.

What it gets in return is a customer who pays Rs. 1,500 monthly and Rs. 18,000 annually, at the minimum. Assuming these new customers stay with MTS for at least another year after the offer — an assumption that is neither too ambitious nor common — the offer has a net present value of Rs. 20,000 for MTS. In other words, it stands to make that much from each new customer signed this way.

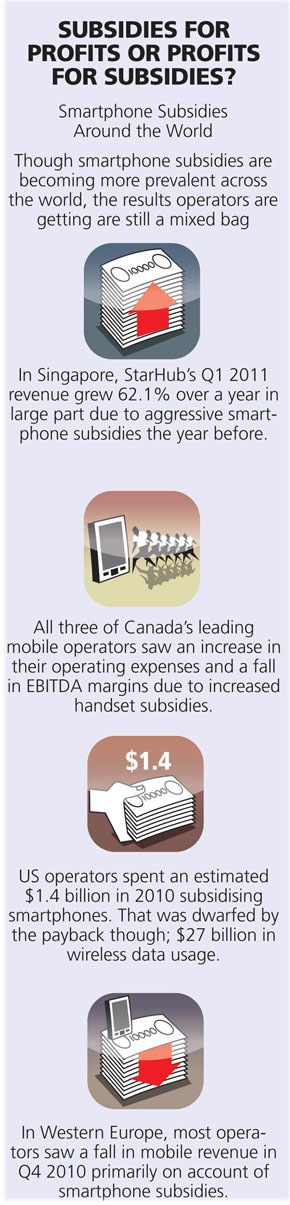

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

That’s not all. Many customers end up spending even more. “Our offer is designed to attract the heavy users who, after sampling the better user experience and networks speeds, end up crossing the minimum commitments on both minutes and megabytes,” says Musatov.

Alok Shende, the head of telecom consulting firm Ascentius, calls this “a priori customer selection”. “Unlike the past where these offers were designed to attract new customers into the telecom network, this time you’re using them to attract users who change their phones every two years, consume data significantly and have high ARPU (average revenue per user).”

Smartphones are also a cornerstone in operator strategies towards increasing data traffic and revenues.

“According to my knowledge no operator is making money on new voice customers, hence everybody wants to move to data. And for selling data, I expect more operators to subsidise handsets,” says S.N. Rai, co-founder and director of home grown handset company Lava.

Smartphones, thanks to their large screens, fast processors and slick software, are the best way for operators to spur data consumption.

Telecom networks around the world have seen exponential data usage from smartphone users compared to featurephone ones, in many cases, as high as 10 times.

But due to their relatively higher prices, smartphones have not yet become mainstream in India. Which brings us to the chicken-or-egg situation Indian operators are trying to solve: They need smartphones to drive wider data usage among subscribers, but their higher prices mean not enough customers are buying them.

“For tablets and smartphones, bundling is the way forward. Only then can we kick-start their adoption,” says Rai.

Musatov says sales of the subsidised handset have been doubling every month since its launch, forcing MTS to order additional stocks from HTC. “We are also offering free (USB) data dongles to customers. And future smartphones we launch will also be sold using this model. Fundamentally, we are believers in this model,” he adds.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)